1. Introduction

Hypertension represents a massive global health issue and is one of the most important cardiovascular risk factors. Hypertension-mediated organ damage (HMOD) is common in patients with severe or long-standing hypertension and is also prevalent in less severe hypertension, even in asymptomatic individuals with elevated blood pressure [1]. It is important to note that at any given blood pressure category above the normal or optimal, the presence of HMOD is associated with a 2- to 3-fold increase in the cardiovascular risk [2]. Up to 40% of newly diagnosed hypertensive patients already have HMOD, predominantly functional and structural alterations of heart, kidneys, eyes, brain, and peripheral arteries [3].

Hypertension is a well-established risk factor for the development of coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) [4]. The constant high pressure within the larger arteries can lead to damage and remodeling of the smallest arteries and arterioles in the microcirculation, capillaries, and venules, affecting their ability to regulate blood flow [5]. This leads to structural and functional remodeling of the coronary microcirculation, in which endothelial dysfunction is one of the most important pathogenetic mechanisms [6]. The endothelium plays a crucial role in regulating blood vessel tone and controlling blood flow. In hypertensive individuals, endothelial dysfunction significantly contributes to the development of CMD, which progressively leads to increased resistance in coronary microcirculation and limited blood flow, causing a reduced oxygen supply to the myocardium [7]. This is why the finding of myocardial ischemia as a result of CMD is relatively common in patients with hypertension, especially in patients with hypertensive heart disease (HHD). Many additional risk factors also contribute to the development of CMD in hypertensive patients, including metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, smoking, and others [8,9,10]. As the development of hypertensive heart disease progresses, left ventricular hypertrophy is more pronounced, consequently leading to more severe impairment of coronary microcirculation. These changes, accompanied by myocardial fibrosis, lead to an increased risk of heart failure with both preserved (HFpEF) and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) [11,12]. This is why coronary microvascular dysfunction significantly affects the morbidity and mortality of patients, demanding more purposeful diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms.

The purpose of this narrative review is to describe the relationship between coronary microvascular dysfunction and systemic hypertension, as well as its pathogenetic mechanisms, characteristics, and potential role in the development of adverse cardiovascular events, especially heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

2. Pathogenetic Mechanisms of Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction

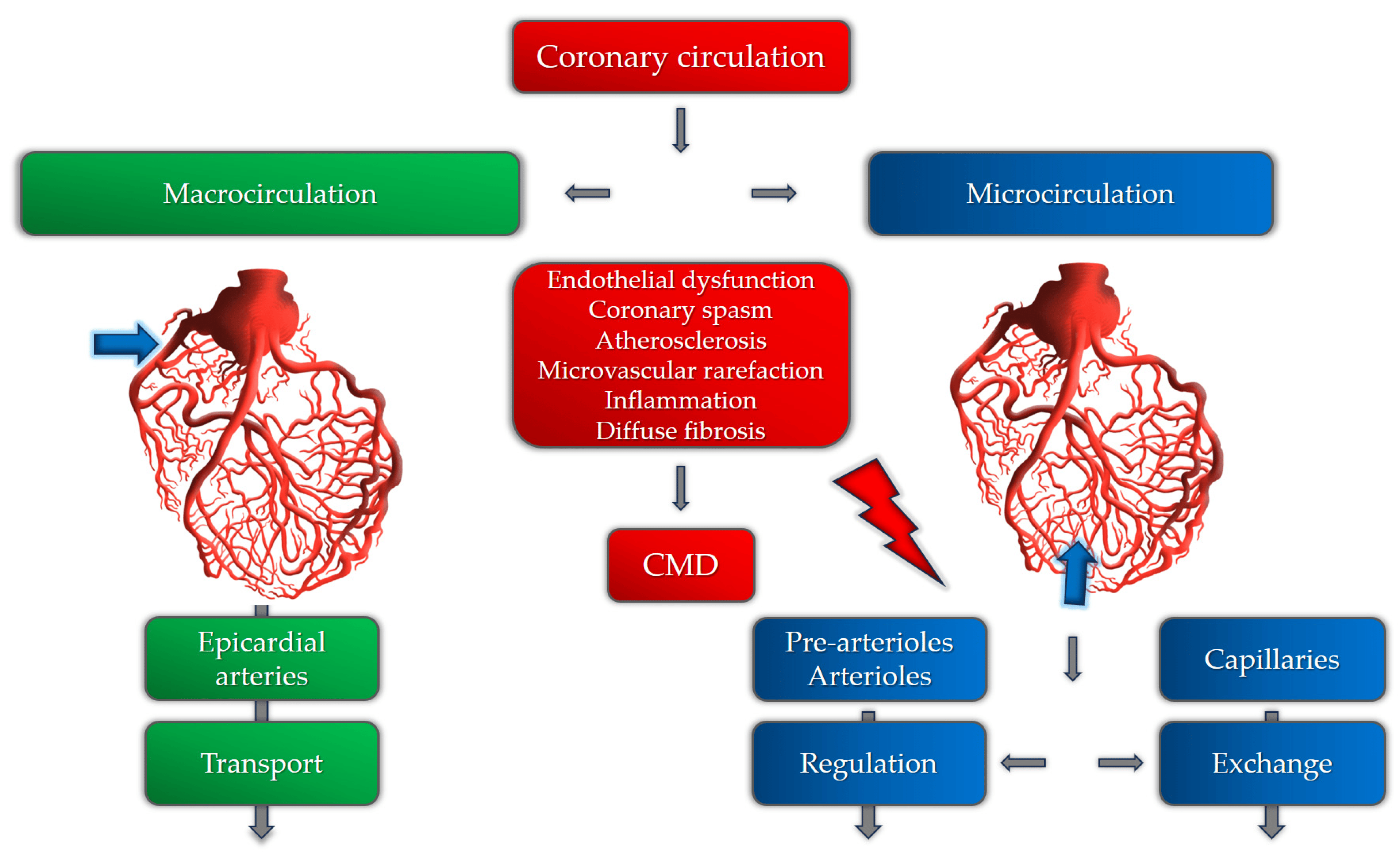

The coronary microcirculation consists of pre-arterioles, arterioles, and capillaries. The main aim of coronary microvasculature is to match blood supply to myocardial oxygen consumption. Any increase in oxygen consumption leads to increased oxygen demands, consequently leading to an increase in myocardial blood flow (MBF). The main role in the control of myocardial blood flow is played by pre-arterioles and arterioles by controlling arterial diameter and tone. In coronary microvascular dysfunction, various mechanisms involved in this process are disrupted by several factors [Figure 1].

Figure 1. Coronary circulation and the role of different pathogenetic mechanisms involved in CMD.

The mechanisms involved in CMD can be structural, functional, or a combination of both [13]. The main pathogenetic mechanisms of coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients with hypertension are still insufficiently researched. Until now, it has been postulated that the pathogenetic basis for the development of CMD involves a variety of mechanisms, including microvascular spasm, endothelial dysfunction, sympathetic over-activity, influence of female hormones, certain psychological disorders, and others [14,15]. These mechanisms are more likely to cause CMD in susceptible patients with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, or diabetes mellitus [16]. In patients with hypertension, the development of left ventricular hypertrophy and the subsequent development of myocardial fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction are important mechanisms of CMD due to several functional and anatomical changes in the microcirculation [17]. Maladaptive mechanisms in hypertension, perivascular fibrosis, and the thickening and rarefaction of small vessel walls, are responsible for increased microvascular resistance and inappropriate blood flow distribution [18]. Also, several functional mechanisms are described as causes of CMD in patients with hypertension, including reduced nitric oxide availability as the most important one [19,20]. It is shown that chronic renin–angiotensin system (RAS) over-activity, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase, cyclooxygenase, xanthine oxidase, and uncoupled endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NOS), as sources of reactive oxygen species, are the main causes of NO deficiency [21]. Also, adrenergic activation and prolonged vasoconstriction can also lead to microvascular remodeling and rarefaction, causing ischemia and clinically manifested angina [22,23]. It is also important to note that certain studies registered these microvascular changes even in patients without elevated blood pressure, suggesting that microvascular dysfunction and remodeling can precede the onset and development of hypertension [24,25]. However, this cause–effect relationship needs further investigation.

Microvascular Angina and Endothelial Dysfunction

Endothelial dysfunction is bi-directionally related to systemic hypertension. It has been shown that the endothelium controls vascular smooth muscle tone in response to various agents, as well as participating in the pathogenesis of hypertension by producing different mediators with systemic effects [26]. In patients with hypertension, endothelial dysfunction is mainly characterized by impaired nitric oxide synthesis and availability, as well as prostacyclin (PGI2) and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) deficiency [27]. On the other hand, as a response to reactive oxygen species, increased production of endothelium-derived vasoconstrictors (mainly endothelin-1 and angiotensin-converting enzyme) has been observed [28]. This is subsequently associated with the development of vascular inflammation, vascular remodeling, and atherosclerosis. As a result, vasoconstrictive, pro-inflammatory, and pro-thrombotic mediators cause increased vasoconstrictive microvascular reactivity [29]. This process leads to both functional and structural changes in the microvasculature and the development of microvascular dysfunction. It is important to emphasize that CMD in patients with hypertension is not solely a result of hypertension but a multifactorial disease with a significant impact on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

3. Additional Risk Factors

3.1. Sex-Related Differences in Patients with Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction and Hypertension

Coronary microvascular dysfunction is more prevalent in women than in men [30]. Early works on estimating the sex-related differences in coronary microcirculation revealed lower coronary flow reserve (CFR) values in women, predominantly due to differences in resting coronary flow [31]. This is also in relation to different mechanisms involved with autonomic regulation and response to oxidative stress, adenosine, endothelin-1, and angiotensin II [32]. It is also notable that women have a smaller vessel size than men, which can contribute to lower CFR values [33]. Studies on cardiac magnetic resonance revealed specific differences, where women in comparison with men had fewer or no associations between the development of CMD and traditional risk factors, including hyperlipidemia, diabetes, smoking, and obesity [34]. This can mainly be the effect of ovarian hormone deficiency, as microvascular angina and estrogen deficiency in hypertensive women have demonstrated an association [35]. In the subgroup of both premenopausal and postmenopausal women with hypertension, ovarian dysfunction and consequent estrogen deficiency played a role in the pathogenesis of CMD [36]. Also, certain psychological factors can play an important role in the development of coronary artery disease, as well as CMD [37]. It is demonstrated that psychological stress induces endothelial dysfunction and vasomotor disorders more often in young women than in men [38].

3.2. Metabolic Syndrome

Metabolic syndrome includes a cluster of conditions such as central obesity, dyslipidemia, high blood pressure, and impaired fasting glucose, all related to an increased cardiovascular risk [39]. Several studies have demonstrated a correlation of different variables with the presence of microvascular dysfunction in these patients, including age, sex, pulse pressure, fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and albuminuria [40]. Among patients with hypertension, it is shown that patients with metabolic syndrome have a more severe form of CMD than those without metabolic syndrome. Sucato et al. demonstrated that these patients had worse coronary perfusion than patients with diabetes mellitus [41].

3.3. Obesity

Obesity has been linked to chronic metabolic disorders, resulting in poor clinical outcomes. Increased oxidative stress, sympathetic nervous system over-activity, and low-grade systemic inflammation are the main mechanisms of coronary microvascular dysfunction in obese individuals [42]. The metabolic activity of adipose tissue, as well as different cytokines and adipokines, are responsible for reduced NO-mediated dilatation, changed endothelial and smooth muscle-dependent vasoregulation mechanisms, and altered vasomotor control. In patients with hypertension, additional volume overload and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy contribute to vascular remodeling. The thickness of epicardial fat tissue, which reflects visceral adiposity rather than general obesity, is also predictive of an impaired coronary vasodilator capacity [43]. A study by Bajaj et al. demonstrated that obese patients with CMD have a 2.5-fold higher risk of developing adverse clinical events [44]. It has been shown that patients with central obesity have lower values of myocardial blood flow than patients with excess weight and no central obesity. This is important to notice, as cardiovascular risk estimation based on waist-to-height ratio and the presence of central obesity becomes more prevalent than that based on BMI, which is recognizable especially in the case of “obesity paradox” and patients with heart failure [45]. Considering the variety of metabolic disorders in the obese population, weight loss and intensified risk-factor control in patients with CMD play an important role in improving angina symptoms, as presented in a study by Bove et al. [46].

3.4. Diabetes Mellitus

The key mechanisms of CMD in patients with diabetes are impaired coronary arteriole vasomotion, including impaired endothelial-mediated vasodilation, hypoxia-induced vasodilation, and myogenic response [47]. It has been shown that hyperglycemia and insulin resistance play central roles in the development of CMD by leading to oxidative stress, inflammatory activation, and endothelial dysfunction [48]. In the later stage of diabetes, structural changes occur. Thickening of the capillary basement membrane and of the arteriole wall results in luminal narrowing, perivascular fibrosis with focal constriction, and capillary rarefaction. These mechanisms lead to increased coronary microvascular resistance and reduced coronary flow reserve and can cause myocardial ischemia [49]. CMD is common in patients with diabetes and can be present with or without the finding of significant epicardial coronary artery disease. It has been shown, by certain studies, that more than 70% of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus have CMD, which can seriously affect future cardiovascular events and prognosis, especially in those with acute myocardial infarction and heart failure [50].

3.5. Hypercholesterolemia

Numerous studies have shown that hypercholesterolemia leads to an inflammatory response within the microvasculature, decreased availability of nitric oxide, and increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [51,52]. Endothelial dysfunction and capillary rarefaction are the two most important mechanisms, leading to severe microvascular impairment in different organs and provoking glomerulopathy-induced kidney dysfunction and hypertension, reduction in coronary flow reserve leading to coronary microvascular dysfunction, and hepatic dysfunction, as in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [53]. It has been shown that the role of specific vasoactive substances is related to both hypercholesterolemia and hypertension, as well as the development of CMD, predominantly endothelium-dependent microvascular dysfunction. This is representative of the pathway of thromboxane A2, which has an important role in platelet aggregation, vasoconstriction, and proliferation [54]. Certain studies demonstrated that patients with uncontrolled hypertension and hypercholesterolemia had increased thromboxane A2 production, which resulted in excessive vasoconstriction, arteriolar remodeling, and capillary rarefaction [55].

3.6. Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a condition linked to increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [56]. Repetitive episodes of hypoxemia lead to the excessive production of reactive oxygen species, the development of low-grade inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction. It has been shown that patients with moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea have lower values of CFR [57]. However, the exact influence of OSA on the development and progression of CMD is hard to observe, as these patients usually have several other risk factors related to CMD, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and hyperlipidemia.

3.7. Smoking

Cigarette smoke is known as the exertion factor with the most detrimental effects on the endothelium, especially the coronary endothelial system [58]. Various toxic components can cause severe endothelial damage, reduce hyperemic coronary blood flow velocity, and provoke the development of microvascular dysfunction. Regarding the presence of CMD, Gullu et al. demonstrated that smokers without obstructive epicardial coronary disease had significantly lower values of coronary flow velocity reserve (CFVR) than the control group [59]. On the other hand, even in patients with epicardial coronary artery disease, smoking was associated with impaired invasively derived indices of coronary microvascular dysfunction, which can additionally contribute to a worse prognosis [60].

4. Diagnostics for Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction in Patients with Hypertension

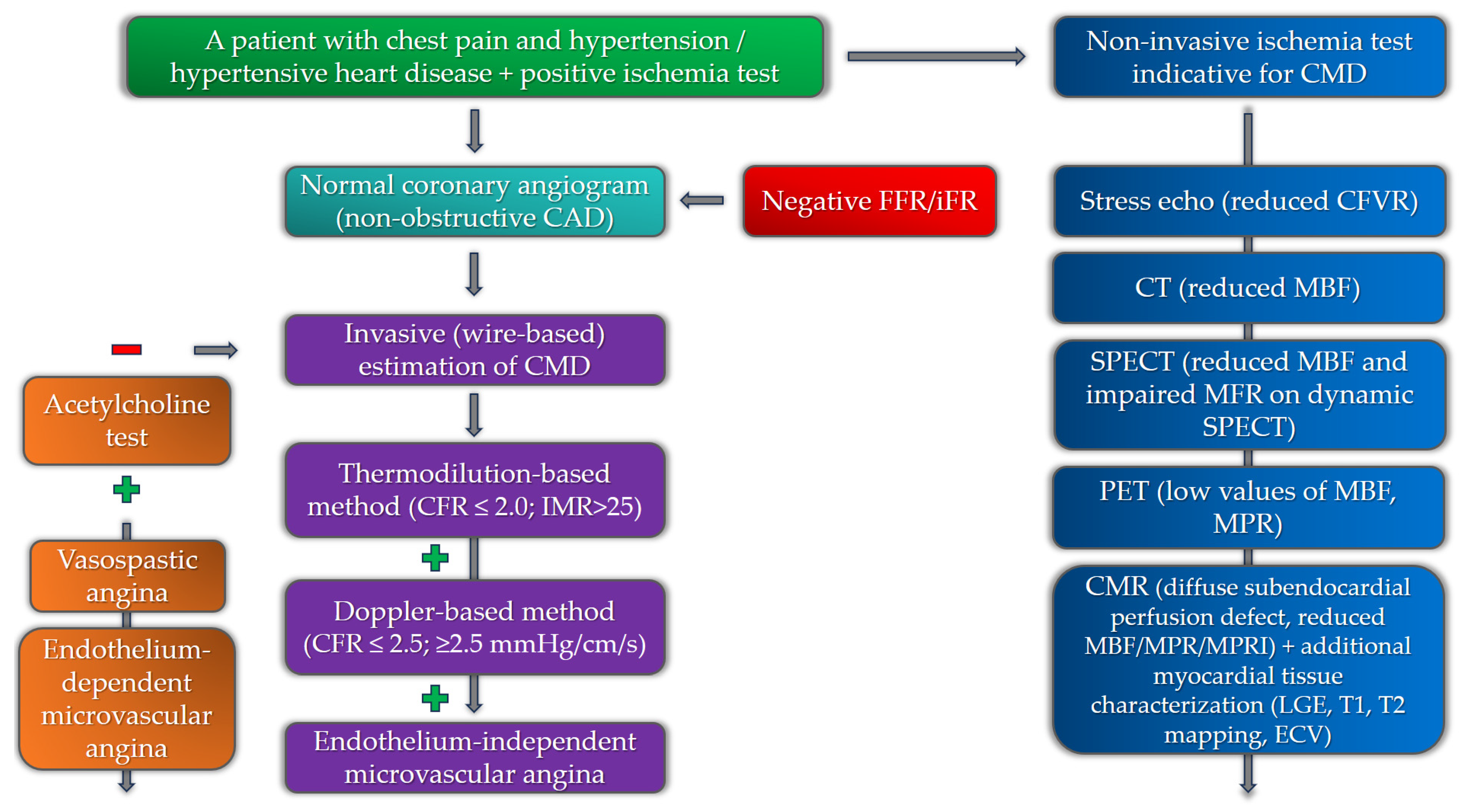

In recent years, several important diagnostic algorithms have been presented regarding CMD that aim to integrate both non-invasive and invasive modalities [61]. The diagnostic algorithm in patients with suspected CMD starts with the exclusion of significant epicardial coronary artery disease. Although CMD can be present in patients with obstructive CAD, the presence of CMD in the absence of obstructive CAD is extremely important to diagnose, especially in patients with additional risk factors for the development of adverse cardiovascular events, primarily heart failure [62]. In patients with microvascular angina, non-invasive diagnostic imaging modalities, primarily echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR), are important for the evaluation of alternative causes of chest pain, including structural and inflammatory conditions [63]. Patients with a negative coronary angiogram, a positive stress test for myocardial ischemia, and additional risk factors for the development of CMD (especially those with hypertensive heart disease) should be considered for non-invasive and invasive investigation of CMD.

4.1. Non-Invasive Diagnostics

4.2. Invasive Diagnostics

The invasive modalities in the diagnostics of CMD are mainly based on the estimation of coronary blood flow. Coronary blood flow can be estimated by Doppler (measuring coronary flow velocity) or thermodilution (measuring cold bolus transit time), each with a different sensor-tipped intracoronary guidewire [90]. In regard to the endothelium function, coronary blood flow can be estimated in response to adenosine (non-endothelium-dependent function) or in response to acetylcholine to evaluate the presence of vasospastic angina (endothelium-dependent function). CFR values (the ratio of the maximal or hyperemic flow to the resting flow) of less than 2.0–2.5 (thermodilution) or 2.5 (Doppler) in the absence of epicardial obstructive coronary artery disease indicate the presence of coronary microvascular dysfunction [91]. The ratio between myocardial perfusion reserve and flow can be used to calculate coronary microvascular resistance (CMR). In the thermodilution-based method, the index of microvascular resistance (IMR) with a cut-off value of >25 is significant for confirming the presence of CMD, while in the Doppler-based technique, the resulting index is called hyperemic microvascular resistance (hMR), with the cut-off value of ≤2.5 mmHg/cm/s [92,93]. Regarding endothelium-dependent microvascular dysfunction, the diagnosis can be made if there is an increase of less than 50% in coronary blood flow, accompanied by ischemic ECG changes and angina symptoms, and in the absence of epicardial vasoconstriction. It is important to have in mind that patients with CMD may have both endothelium-dependent and -independent types of microvascular dysfunction. Studies evaluating the invasive indices of CMD in patients with HFpEF revealed abnormalities in coronary flow and resistance [94]. The study by Dryer et al. revealed that HFpEF patients had lower CFR and higher IMR values than the control group. These patients were also older and had higher values of NT-proBNP and higher left ventricular end-diastolic pressure, while 93% of them had hypertension as one of the comorbidities [95].

The diagnostic algorithm for the estimation of CMD among patients with chest pain and hypertension, involving both non-invasive and invasive modalities, is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Diagnostic algorithm for the estimation of coronary microvascular dysfunction among hypertensive patients with chest pain (negative and positive symbols correspond to a negative or positive test in the diagnostic algorithm).

Considering the variety of imaging modalities in diagnostics for CMD, it is notable to mention that in patients with hypertension, the indices of arterial stiffness are independently related to microvascular dysfunction [96,97,98]. A recent study by Aursulesei Onofrei et al. demonstrated a predictive value of the subendocardial viability ratio (SEVR), also known as the Buckberg index, in hypertensive patients with CMD. This parameter of arterial stiffness, which represents an index of myocardial oxygen supply and demand, is significant in the assessment of long-term cardiovascular risk and is independently associated with age, abdominal circumference, and Framingham risk score [99].

5. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction, Hypertension, and HFpEF

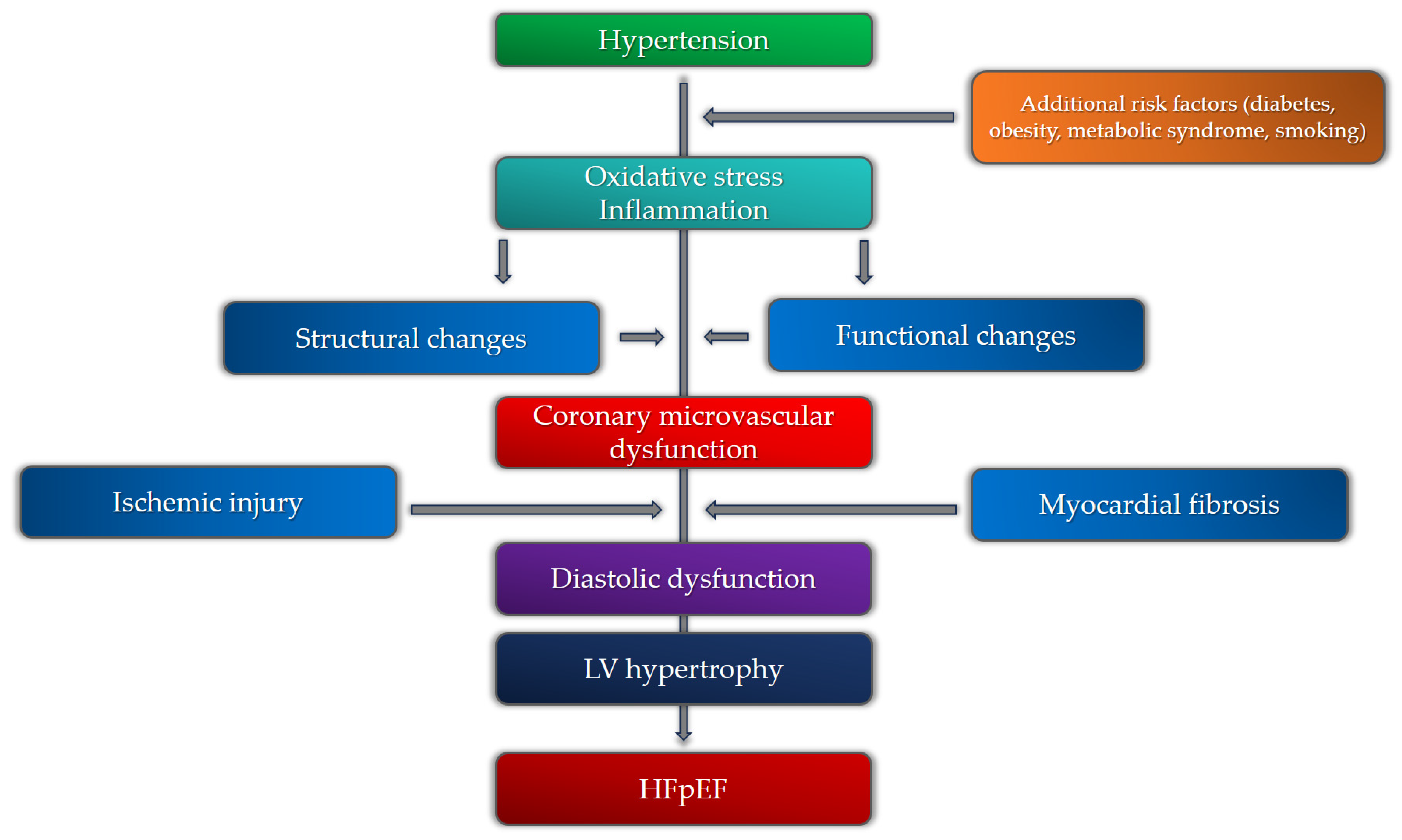

Recent studies that researched the pathophysiology of HFpEF and the role of CMD revealed that, across various studies, 40–86% of patients with HFpEF have coronary microvascular dysfunction, proven by both non-invasive and invasive diagnostic modalities [100,101]. It is still uncertain whether CMD is a cause or a consequence of HFpEF. Since myocardial interstitial and focal fibrosis is one of the main mechanisms in HFpEF responsible for increased myocardial stiffness, it is believed that CMD and its consequences are at the core of HFpEF pathophysiology, mostly due to chronic microvascular inflammation [102]. The emerging role of inflammation in the development of HFpEF has been the subject of numerous studies in recent years. In patients with hypertension, inflammation is driven mainly by oxidative stress, inducing hypertension-related vascular aging through various mediators [103]. This process is shown to be one of the main mechanisms in the development and progression of HFpEF. Kanagala et al. demonstrated that CMD is an independent predictor of all-cause mortality and heart failure hospitalizations in patients with HFpEF [104]. It is important to note that a variety of other parameters were found to correlate with CMD and HFpEF, including age, heart rate, diastolic blood pressure, hemoglobin, urea, creatinine, eGFR, BNP, usage of loop diuretics, and increased LV filling pressures. Hypertension is one of the most important factors for the development of endothelial dysfunction and the promotion of pro-hypertrophic and pro-fibrotic signaling, thus directly increasing the risk for the development of CMD, diffuse and focal fibrosis, and HFpEF [105]. It has been shown that a significant number of patients with HFpEF exhibit hypertension as a comorbidity (up to 90%) [106]. The presence of CMD and hypertension, or more precisely, hypertensive heart disease, have prognostic significance in patients with HFpEF. Extracellular volume fraction, a marker of interstitial fibrosis assessed by cardiac magnetic resonance, is one of the most important parameters to discriminate between HHD and HFpEF. The amount of interstitial fibrosis that clinically correlates with significant LV stiffness, the development of HFpEF, and the transition from HHD to HFpEF is a value of ECV of 31.2%. This value can discriminate between HFpEF and HHD with 100% sensitivity and 75% specificity [107]. One more parameter derived from non-invasive diagnostic modalities that can differentiate between HHD and HFpEF is the global longitudinal strain (GLS). In hypertensive heart disease and in HFpEF, fibrosis involves the myocardial mid-wall, where circumferential shortening fibers are located, which is why global circumferential strain (GCS) is affected before longitudinal shortening. It has been found that GLS is significantly more depressed in patients with HFpEF than in patients with HHD, marking it as a more powerful prognostic marker in HFpEF [108]. One of the possible explanations could be the more pronounced focal, and especially interstitial, fibrosis in HFpEF patients as a consequence of advanced stages of CMD and LV hypertrophy. However, the exact relationship between all these clinical entities is yet to be determined. The cause-and-effect relationship between hypertension, numerous risk factors, and CMR in the development of HFpEF is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Pathophysiological mechanisms of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) in relation to coronary microvascular dysfunction and hypertension.

6. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction, Hypertension, and Atrial Fibrillation

As previously mentioned, myocardial fibrosis is one of the main consequences of both hypertensive heart disease and coronary microvascular dysfunction and is also an important pathophysiological mechanism of HFpEF. Cardiac magnetic resonance studies demonstrated the presence of myocardial fibrosis not only in the LV myocardium but also in the left atrium, subsequently increasing the risk of atrial fibrillation occurrence [109]. It is notable that, aside from being the most prevalent sustained arrhythmia in clinical practice, atrial fibrillation is particularly common in patients with HFpEF [110]. Although there is a lack of evidence on the exact relationship between CMD and AF, it is proposed that impaired myocardial perfusion in patients with CMD causes atrial remodeling and electrical instability, thus facilitating the occurrence of AF in patients with CMD. Recent studies evaluating the presence and impact of AF in patients with HFpEF revealed that AF is present in 79% of patients with HFpEF [111]. Among patients with AF and HFpEF, more than 90% of patients have impaired invasively derived values of CFR, indicating the presence of CMD. It is important to underline that in these patients, hypertension was significantly more prevalent, contributing to the development of CMD, AF, and HFpEF. Based on the above, it is important to search for CMD in patients with hypertension and atrial fibrillation, as these patients have an increased risk of developing HFpEF.

7. Management of Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction in Patients with Hypertension

Having in mind the variety of pathophysiological mechanisms and different clinical phenotypes, the management of coronary microvascular dysfunction is a challenging task. It is mainly a combination of pharmacological treatment and lifestyle modification, although, in the last few years, several interventional techniques have appeared as potential therapeutic solutions. Lifestyle interventions, including smoking cessation, weight loss, regular exercise, and improved nutrition, have demonstrated positive effects on microvascular function [112,113]. It is shown that the optimization of underlying diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia, and also the treatment of hypertension, as one of the most important risk factors, is beneficial in patients with CMD [114]. Early and continuous regulation of hypertension in patients with CMD is significant, as it can slow down the occurrence and progression of several subclinical and clinical entities such as left ventricular hypertrophy, interstitial myocardial fibrosis, and diastolic dysfunction. This can reduce the ischemic burden, improve symptoms, and reduce the risk of adverse events, especially HFpEF. AEC inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), calcium channel blockers, and beta blockers with vasodilatory properties have substantial effects on improving microvascular perfusion [115,116,117]. Regarding the effects of ACE inhibitors, it is shown that certain medications can also slow down and even reverse reactive interstitial fibrosis, which is important in patients with hypertension [118]. The ongoing trial regarding the interventional treatment of hypertension (renal denervation) tends to suggest the positive effects of this procedure on patients with hypertension-related microvascular dysfunction, although the results of previous studies were controversial [117]. Considering the already proven positive effects of renal denervation on cardiac morphology and function, the additional effects on the improvement of microvascular function can be helpful in preventing both HFpEF and HFrEF [119]. Interventional procedures for the treatment of microvascular angina have been under development in recent years with promising results. The implantation of a coronary sinus reducer, which leads to a significant reduction in vascular resistance in the subendocardium, showed positive effects on angina symptom relief in patients with CMD [120]. Future studies should demonstrate the overall clinical benefit of this procedure in everyday practice.

8. Prognosis

Recent studies that investigated the prognostic significance of invasively derived indices of CMD revealed that depressed CFR was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular death and heart failure admission, while elevated IMR alone still has a limited prognostic value [121]. It is still unclear why IMR has uncertain prognostic significance in patients with preserved CFR. However, one of the possible explanations can be that impaired IMR value can be an earlier indicator of CMD in the subclinical phase of the disease, with dominant functional alterations of the microcirculation. On the other hand, depressed CFR is more significant in the clinical phase of the disease, reflecting both functional and structural alterations, and is more associated with clinical outcomes in these patients. Non-invasive estimation of myocardial perfusion seems to have an additional prognostic significance. The greatest number of studies refer to CMR and PET as the two most important non-invasive modalities. In PET studies, there was a positive correlation with clinical outcomes in the group of patients with both epicardial and microvascular coronary artery disease, as well as with CMD solely [122]. The reduction of myocardial flow reserve was associated with the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in both of these groups. The study by Murthy et al. demonstrated that there was a 3-year cardiac mortality rate of 8% in patients with impaired MFR, among which over 80% had hypertension as a comorbidity [123].

Quantitative CMR methods of estimating myocardial perfusion demonstrated a significant correlation with major adverse cardiovascular events. The value of MPRI (myocardial perfusion reserve index) below the optimal predictive threshold value of 1.47 was related to a three-fold increased risk of having MACE in the 5-year follow-up. It is important to underline that hypertension, alongside MPRI value, was also a significant predictor of poor prognosis in these patients, indicating an important mutual relationship between microvascular angina and hypertension [124].

9. Future Perspectives

A more integrated algorithm of CMD diagnostics, especially in symptomatic patients and patients with increased risk of HFpEF, is mandatory. This is important not only to control symptoms but also to minimize the possibility of future adverse cardiovascular events. Investigating the relationship between different clinical entities, especially CMD, myocardial fibrosis, hypertensive heart disease, and HFpEF, will be helpful in the proper identification of patients at risk and also to guide further development of different therapeutic modalities.

10. Conclusions

Coronary microvascular dysfunction is a clinical entity linked with various risk factors that significantly affect cardiac morbidity and mortality. Hypertension, one of the most important, causes both functional and structural alterations in the microvasculature, promoting the occurrence and progression of microvascular dysfunction. CMD is also related to several hypertension-induced morphological and functional changes in the myocardium in the subclinical and early clinical stages. This indicates the fact that CMD, especially if associated with hypertension, is a subclinical marker of end-organ damage and heart failure, particularly that with preserved ejection fraction. This comprehensive review provides an integrated diagnostic approach for patients with hypertension and suspected CMD, as well as an overview of current therapeutical modalities in order to reduce the burden of this emerging condition.

References

- Zhou, B.; Perel, P.; Mensah, G.A.; Ezzati, M. Global epidemiology, health burden and effective interventions for elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasan, R.S.; Song, R.J.; Xanthakis, V.; Beiser, A.; DeCarli, C.; Mitchell, G.F.; Seshadri, S. Hypertension-Mediated Organ Damage: Prevalence, Correlates, and Prognosis in the Community. Hypertension 2022, 79, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benas, D.; Triantafyllidi, H.; Birmpa, D.; Fambri, A.; Schoinas, A.; Thymis, I.; Kostelli, G.; Ikonomidis, I. Hypertension-Mediated Organ Damage in Young Patients with First-Diagnosed And Never Treated Systolic Hypertension. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2023, 21, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wei, J.; AlBadri, A.; Zarrini, P.; Merz, C.N.B. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction—Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Prognosis, Diagnosis, Risk Factors and Therapy. Circ. J. 2016, 81, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, C.; Berry, C. Definition and epidemiology of coronary microvascular disease. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2022, 29, 1763–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancheri, F.; Longo, G.; Vancheri, S.; Henein, M. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godo, S.; Takahashi, J.; Yasuda, S.; Shimokawa, H. Endothelium in Coronary Macrovascular and Microvascular Diseases. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2021, 78 (Suppl. S6), S19–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labazi, H.; Trask, A.J. Coronary microvascular disease as an early culprit in the pathophysiology of diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 123, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, W.B.; Barrett, E.J. Microvascular Dysfunction in Diabetes Mellitus and Cardiometabolic Disease. Endocr. Rev. 2021, 42, 29–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibel, A.; Selthofer-Relatic, K.; Drenjancevic, I.; Bacun, T.; Bosnjak, I.; Kibel, D.; Gros, M. Coronary microvascular dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. J. Int. Med. Res. 2017, 45, 1901–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.P.; Glynn, R.J.; Schneeweiss, S.; Lin, K.J.; Patorno, E.; Barberio, J.; Levin, R.; Evers, T.; Wang, S.V.; Desai, R.J. Risk Factors for Heart Failure with Preserved or Reduced Ejection Fraction Among Medicare Beneficiaries: Application of Competing Risks Analysis and Gradient Boosted Model. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 12, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, W.J.; Tschöpe, C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crea, F.; Montone, R.A.; Rinaldi, R. Pathophysiology of Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction. Circ. J. 2022, 86, 1319–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masi, S.; Rizzoni, D.; Taddei, S.; Widmer, R.J.; Montezano, A.C.; Lüscher, T.F.; Schiffrin, E.L.; Touyz, R.M.; Paneni, F.; Lerman, A.; et al. Assessment and pathophysiology of microvascular disease: Recent progress and clinical implications. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 2590–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suda, A.; Takahashi, J.; Hao, K.; Kikuchi, Y.; Shindo, T.; Ikeda, S.; Sato, K.; Sugisawa, J.; Matsumoto, Y.; Miyata, S.; et al. Coronary Functional Abnormalities in Patients with Angina and Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 2350–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorop, O.; Heinonen, I.; van Kranenburg, M.; van de Wouw, J.; de Beer, V.J.; Nguyen, I.T.N.; Octavia, Y.; van Duin, R.W.B.; Stam, K.; van Geuns, R.-J.; et al. Multiple common comorbidities produce left ventricular diastolic dysfunction associated with coronary microvascular dysfunction, oxidative stress, and myocardial stiffening. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018, 114, 954–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiecinski, J.; Lennen, R.J.; Gray, G.A.; Borthwick, G.; Boswell, L.; Baker, A.H.; Newby, D.E.; Dweck, M.R.; Jansen, M.A. Progression and regression of left ventricular hypertrophy and myocardial fibrosis in a mouse model of hypertension and concomitant cardiomyopathy. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2020, 22, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Moraes, R.; Tibirica, E. Early Functional and Structural Microvascular Changes in Hypertension Related to Aging. Curr. Hypertens. Rev. 2017, 13, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, M.; Flammer, A.; Lüscher, T.F. Nitric oxide in hypertension. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2006, 8, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, G.M.; da Silva, M.C.; Nascimento, D.V.G.; Lima Silva, E.M.; Gouvêa, F.F.F.; de França Lopes, L.G.; Araújo, A.V.; Ferraz Pereira, K.N.; de Queiroz, T.M. Nitric Oxide as a Central Molecule in Hypertension: Focus on the Vasorelaxant Activity of New Nitric Oxide Donors. Biology 2021, 10, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montezano, A.C.; Touyz, R.M. Reactive oxygen species, vascular Noxs, and hypertension: Focus on translational and clinical research. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt, M.M.; Cheng, C.; Merkus, D.; Duncker, D.J.; Sorop, O. Mechanobiology of Microvascular Function and Structure in Health and Disease: Focus on the Coronary Circulation. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 771960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pries, A.R.; Badimon, L.; Bugiardini, R.; Camici, P.G.; Dorobantu, M.; Duncker, D.J.; Escaned, J.; Koller, A.; Piek, J.J.; de Wit, C. Coronary vascular regulation, remodelling, and collateralization: Mechanisms and clinical implications on behalf of the working group on coronary pathophysiology and microcirculation. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 3134–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Konst, R.; Guzik, T.J.; Kaski, J.-C.; Maas, A.H.E.M.; E Elias-Smale, S. The pathogenic role of coronary microvascular dysfunction in the setting of other cardiac or systemic conditions. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Wai, K.L.; McGeechan, K.; Ikram, M.K.; Kawasaki, R.; Xie, J.; Klein, R.; Klein, B.B.; Cotch, M.F.; Wang, J.J.; et al. Retinal vascular caliber and the development of hypertension: A meta-analysis of individual participant data. J. Hypertens. 2014, 32, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharmashankar, K.; Widlansky, M.E. Vascular endothelial function and hypertension: Insights and directions. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2010, 12, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, K.; Ohtsubo, T.; Kitazono, T. Endothelium-Dependent Hyperpolarization (EDH) in Hypertension: The Role of Endothelial Ion Channels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostov, K. The Causal Relationship between Endothelin-1 and Hypertension: Focusing on Endothelial Dysfunction, Arterial Stiffness, Vascular Remodeling, and Blood Pressure Regulation. Life 2021, 11, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilos, M.; Petousis, S.; Parthenakis, F. Interaction between platelets and endothelium: From pathophysiology to new therapeutic options. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2018, 8, 568–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aribas, E.; Roeters van Lennep, J.E.; E Elias-Smale, S.; Piek, J.J.; Roos, M.; Ahmadizar, F.; Arshi, B.; Duncker, D.J.; Appelman, Y.; Kavousi, M. Prevalence of microvascular angina among patients with stable symptoms in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease: A systematic review. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Fearon, W.F.; Honda, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Pargaonkar, V.; Fitzgerald, P.J.; Lee, D.P.; Stefanick, M.; Yeung, A.C.; Tremmel, J.A. Effect of Sex Differences on Invasive Measures of Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction in Patients with Angina in the Absence of Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2015, 8, 1433–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loperena, R.; Harrison, D.G. Oxidative Stress and Hypertensive Diseases. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 101, 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, H.R.; Merz, C.N.B.; Berry, C.; Samuel, R.; Saw, J.; Smilowitz, N.R.; de Souza, A.C.D.A.; Sykes, R.; Taqueti, V.R.; Wei, J. Coronary Arterial Function and Disease in Women with No Obstructive Coronary Arteries. Circ. Res. 2022, 130, 529–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, M.; Shufelt, C.; Mehta, P.K.; Gill, E.; Berman, D.S.; Li, D.; Sharif, B.; Li, N.; Merz, C.N.B.; Thomson, L.E. Cardiac risk factors and myocardial perfusion reserve in women with microvascular coronary dysfunction. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2013, 3, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnabas, O.; Wang, H.; Gao, X.-M. Role of estrogen in angiogenesis in cardiovascular diseases. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2013, 10, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunc, E.; Eve, A.A.; Madak-Erdogan, Z. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction and Estrogen Receptor Signaling. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 31, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, C.; Santarella, L.; Costa, M.G.; Manfrini, O.; Flacco, M.E.; Capasso, L.; Chiarini, S.; Di Baldassarre, A.; Manzoli, L. Pathophysiological mechanisms linking de-pression and atherosclerosis: An overview. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2012, 26, 775–782. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Meer, R.E.; Maas, A.H. The Role of Mental Stress in Ischaemia with No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease and Coronary Vasomotor Disorders. Eur. Cardiol. Rev. 2021, 1, e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottillo, S.; Filion, K.B.; Genest, J.; Joseph, L.; Pilote, L.; Poirier, P.; Rinfret, S.; Schiffrin, E.L.; Eisenberg, M.J. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 56, 1113–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chilian, W.; Nystoriak, M.A.; Sisakian, H.; Ohanyan, V. Coronary microvascular disease during metabolic syndrome: What is known and unknown: Pathological consequences of redox imbalance for endothelial K+ channels. Int. J. Cardiol. 2020, 321, 18–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sucato, V.; Madaudo, C.; Di Fazio, L.; Manno, G.; Vadalà, G.; Novo, S.; Evola, S.; Novo, G.; Galassi, A.R. Impact of Metabolic Syndrome on Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction: A Single Center Experience. Cardiol. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 07, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Abdu, F.A.; Mohammed, A.-Q.; Zhang, W.; Liu, L.; Yin, G.; Feng, Y.; Mohammed, A.A.; Mareai, R.M.; Lv, X.; et al. Prognostic impact of coronary microvascular dysfunction assessed by caIMR in overweight with chronic coronary syndrome patients. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 922264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, I.; Dykun, I.; Kärner, L.; Hendricks, S.; Totzeck, M.; Al-Rashid, F.; Rassaf, T.; Mahabadi, A.A. Epicardial adipose tissue differentiates in patients with and without coronary microvascular dysfunction. Int. J. Obes. 2021, 45, 2058–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, N.S.; Osborne, M.T.; Gupta, A.; Tavakkoli, A.; Bravo, P.E.; Vita, T.; Bibbo, C.F.; Hainer, J.; Dorbala, S.; Blankstein, R.; et al. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction and Cardiovascular Risk in Obese Patients. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, R.; von Haehling, S. Revisiting the obesity paradox in heart failure: What is the best anthropometric index to gauge obesity? Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 1154–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvatore, T.; Galiero, R.; Caturano, A.; Vetrano, E.; Loffredo, G.; Rinaldi, L.; Catalini, C.; Gjeloshi, K.; Albanese, G.; Di Martino, A.; et al. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction in Diabetes Mellitus: Pathogenetic Mechanisms and Potential Therapeutic Options. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormazabal, V.; Nair, S.; Elfeky, O.; Aguayo, C.; Salomon, C.; Zuñiga, F.A. Association between insulin resistance and the development of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2018, 17, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, I.; Frangogiannis, N.G. Diabetes-associated cardiac fibrosis: Cellular effectors, molecular mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2016, 90, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Singh, S.; Liu, L.; Mohammed, A.-Q.; Yin, G.; Xu, S.; Lv, X.; Shi, T.; Feng, C.; Jiang, R.; et al. Prognostic value of coronary microvascular dysfunction assessed by coronary angiography-derived index of microcirculatory resistance in diabetic patients with chronic coronary syndrome. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2022, 21, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallinoro, E.; Paolisso, P.; Candreva, A.; Bermpeis, K.; Fabbricatore, D.; Esposito, G.; Bertolone, D.; Peregrina, E.F.; Munhoz, D.; Mileva, N.; et al. Microvascular Dysfunction in Patients with Type II Diabetes Mellitus: Invasive Assessment of Absolute Coronary Blood Flow and Microvascular Resistance Reserve. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 765071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuelsson, F.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Tybjærg-Hansen, A.; Benn, M. Impact of LDL Cholesterol on Microvascular Versus Macrovascular Disease: A Mendelian Randomization Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 1465–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padró, T.; Vilahur, G.; Badimon, L. Dyslipidemias and Microcirculation. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 2921–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avtaar Singh, S.S.; Nappi, F. Pathophysiology and Outcomes of Endothelium Function in Coronary Microvascular Diseases: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials and Multicenter Study. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H. Role of thromboxane A2 signaling in endothelium-dependent contractions of arteries. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2018, 134, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stapleton, P.A.; Goodwill, A.G.; James, M.E.; Brock, R.W.; Frisbee, J.C. Hypercholesterolemia and microvascular dysfunction: Interventional strategies. J. Inflamm. 2010, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdravkovic, M.; Popadic, V.; Klasnja, S.; Milic, N.; Rajovic, N.; Divac, A.; Manojlovic, A.; Nikolic, N.; Lukic, F.; Rasiti, E.; et al. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Risk: The Role of Dyslipidemia, Inflammation, and Obesity. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 898072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozbas, S.S.; Eroglu, S.; Ozyurek, B.A.; Eyuboglu, F.O. Coronary flow reserve is impaired in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2017, 12, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittilo, M. Cigarette smoking, endothelial injury and cardiovascular disease. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2000, 81, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullu, H.; Caliskan, M.; Ciftci, O.; Erdogan, D.; Topcu, S.; Yildirim, E.; Yildirir, A.; Muderrisoglu, H. Light cigarette smoking impairs coronary microvascular functions as severely as smoking regular cigarettes. Heart 2007, 93, 1274–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haig, C.; Carrick, D.; Carberry, J.; Mangion, K.; Maznyczka, A.; Wetherall, K.; McEntegart, M.; Petrie, M.C.; Eteiba, H.; Lindsay, M.; et al. Current Smoking and Prognosis After Acute ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: New Pathophysiological Insights. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 12, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, G.A.; Morrone, D.; Pizzi, C.; Tritto, I.; Bergamaschi, L.; De Vita, A.; Villano, A.; Crea, F. Diagnostic approach for coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients with chest pain and no obstructive coronary artery disease. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 32, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fordyce, C.B.; Newby, D.E.; Douglas, P.S. Diagnostic Strategies for the Evaluation of Chest Pain: Clinical Implications from SCOT-HEART and PROMISE. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, A.; D’andrea, A.; Sperlongano, S.; Tagliamonte, E.; Mandoli, G.E.; Santoro, C.; Evola, V.; Bandera, F.; Morrone, D.; Malagoli, A.; et al. Echocardiographic assessment of coronary microvascular dysfunction: Basic concepts, technical aspects, and clinical settings. Echocardiography 2021, 38, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, J.; Prescott, E. Doppler Echocardiography Assessment of Coronary Microvascular Function in Patients with Angina and No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 723542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.J.; Lam, C.S.P.; Svedlund, S.; Saraste, A.; Hage, C.; Tan, R.-S.; Beussink-Nelson, L.; Faxén, U.L.; Fermer, M.L.; Broberg, M.A.; et al. Prevalence and correlates of coronary microvascular dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: PROMIS-HFpEF. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 3439–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Völz, S.; Svedlund, S.; Andersson, B.; Li-Ming, G.; Rundqvist, B. Coronary flow reserve in patients with resistant hypertension. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2016, 106, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemmensen, T.S.; Christensen, M.; Løgstrup, B.B.; Kronborg, C.J.S.; Knudsen, U.B. Reduced coronary flow velocity reserve in women with previous pre-eclampsia: Link to increased cardiovascular disease risk. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 55, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaibazzi, N.; Bergamaschi, L.; Pizzi, C.; Tuttolomondo, D. Resting global longitudinal strain and stress echocardiography to detect coronary artery disease burden. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2023, 24, e86–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliamonte, E.; Sperlongano, S.; Montuori, C.; Riegler, L.; Scarafile, R.; Carbone, A.; Forni, A.; Radmilovic, J.; Di Vilio, A.; Astarita, R.; et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction affects left ventricular global longitudinal strain response to dipyridamole stress echocardiography: A pilot study. Heart Vessel. 2023, 38, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, I.; Tesic, M.; Giga, V.; Dobric, M.; Boskovic, N.; Vratonjic, J.; Orlic, D.; Gudelj, O.; Tomasevic, M.; Dikic, M.; et al. Impairment of coronary flow velocity reserve and global longitudinal strain in women with cardiac syndrome X and slow coronary flow. J. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieman, K.; Balla, S. Dynamic CT myocardial perfusion imaging. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2020, 14, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitun, S.; Clemente, A.; De Lorenzi, C.; Benenati, S.; Chiappino, D.; Mantini, C.; Sakellarios, A.I.; Cademartiri, F.; Bezante, G.P.; Porto, I. Cardiac CT perfusion and FFRCTA: Pathophysiological features in ischemic heart disease. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2020, 10, 1954–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ihdayhid, A.R.; Fairbairn, T.A.; Gulsin, G.S.; Tzimas, G.; Danehy, E.; Updegrove, A.; Jensen, J.M.; Taylor, C.A.; Bax, J.J.; Sellers, S.L.; et al. Cardiac computed tomography-derived coronary artery volume to myocardial mass. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2022, 16, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Rosendael, S.E.; van Rosendael, A.R.; Kuneman, J.H.; Patel, M.R.; Nørgaard, B.L.; Fairbairn, T.A.; Nieman, K.; Akasaka, T.; Berman, D.S.; Koweek, L.M.H.; et al. Coronary Volume to Left Ventricular Mass Ratio in Patients with Hypertension. Am. J. Cardiol. 2023, 199, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djaïleb, L.; Riou, L.; Piliero, N.; Carabelli, A.; Vautrin, E.; Broisat, A.; Leenhardt, J.; Machecourt, J.; Fagret, D.; Vanzetto, G.; et al. SPECT myocardial ischemia in the absence of obstructive CAD: Contribution of the invasive assessment of microvascular dysfunction. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2018, 25, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Caobelli, F.; Che, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, X.; Hu, X.; Xu, C.; Fei, M.; Zhang, J.; et al. The prognostic value of CZT SPECT myocardial blood flow (MBF) quantification in patients with ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery disease (INOCA): A pilot study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2023, 50, 1940–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, R.C.; Bourque, J.M.; Salerno, M.; Kramer, C.M. Cardiovascular Imaging Techniques to Assess Microvascular Dysfunction. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 13, 1577–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Brown, J.M.; Bajaj, N.S.; Chandra, A.; Divakaran, S.; Weber, B.; Bibbo, C.F.; Hainer, J.; Taqueti, V.R.; Dorbala, S.; et al. Hypertensive coronary microvascular dysfunction: A subclinical marker of end organ damage and heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 2366–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.R.; Salerno, M.; Kwong, R.Y.; Singh, A.; Heydari, B.; Kramer, C.M. Stress Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Myocardial Perfusion Imaging: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 1655–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdravkovic, M.; Klasnja, S.; Popovic, M.; Djuran, P.; Mrda, D.; Ivankovic, T.; Manojlovic, A.; Koracevic, G.; Lovic, D.; Popadic, V. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance in Hypertensive Heart Disease: Time for a New Chapter. Diagnostics 2022, 13, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Wang, X.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, M.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, T. T1 Mapping and Extracellular Volume in Cardiomyopathy Showing Left Ventricular Hypertrophy: Differentiation between Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and Hypertensive Heart Disease. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2022, 15, 4163–4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engblom, H.; Xue, H.; Akil, S.; Carlsson, M.; Hindorf, C.; Oddstig, J.; Hedeer, F.; Hansen, M.S.; Aletras, A.H.; Kellman, P.; et al. Fully quantitative cardiovascular magnetic resonance myocardial perfusion ready for clinical use: A comparison between cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2017, 19, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorach, B.; Shaw, P.W.; Bourque, J.; Kuruvilla, S.; Balfour, P.C.; Yang, Y.; Mathew, R.; Pan, J.; Gonzalez, J.A.; Taylor, A.M.; et al. Quantitative cardiovascular magnetic resonance perfusion imaging identifies reduced flow reserve in microvascular coronary artery disease. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2018, 20, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, L.E.; Wei, J.; Agarwal, M.; Haft-Baradaran, A.; Shufelt, C.L.; Mehta, P.K.; Gill, E.B.; Johnson, B.D.; Kenkre, T.; Handberg, E.M.; et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance myocardial perfusion reserve index is reduced in women with coronary microvascular dysfunction. A National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-sponsored study from the Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 8, e002481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H.; Scannell, C.M.; Demir, O.M.; Ryan, M.; McConkey, H.; Ellis, H.; Masci, P.G.; Perera, D.; Chiribiri, A. High-Resolution Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging Techniques for the Identification of Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 14, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, A.; Kang, N.; Chung, J.; Gupta, A.R.; Parwani, P. Evaluation of Ischemia with No Obstructive Coronary Arteries (INOCA) and Contemporary Applications of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance (CMR). Medicina 2023, 59, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarsini, R.; Shanmuganathan, M.; De Maria, G.L.; Borlotti, A.; Kotronias, R.A.; Burrage, M.K.; Terentes-Printzios, D.; Langrish, J.; Lucking, A.; Fahrni, G.; et al. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction Assessed by Pressure Wire and CMR After STEMI Predicts Long-Term Outcomes. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 14, 1948–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, K.D.; Seraphim, A.; Augusto, J.B.; Xue, H.; Chacko, L.; Aung, N.; Petersen, S.E.; Cooper, J.A.; Manisty, C.; Bhuva, A.N.; et al. The Prognostic Significance of Quantitative Myocardial Perfusion: An Artificial Intelligence Based Approach Using Perfusion Mapping. Circulation 2020, 141, 1282–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levelt, E.; Piechnik, S.K.; Liu, A.; Wijesurendra, R.S.; Mahmod, M.; Ariga, R.; Francis, J.M.; Greiser, A.; Clarke, K.; Neubauer, S.; et al. Adenosine stress CMR T1-mapping detects early microvascular dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus without obstructive coronary artery disease. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2017, 19, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travieso, A.; Jeronimo-Baza, A.; Faria, D.; Shabbir, A.; Mejia-Rentería, H.; Escaned, J. Invasive evaluation of coronary microvascular dysfunction. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2022, 29, 2474–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangiacapra, F.; Viscusi, M.M.; Verolino, G.; Paolucci, L.; Nusca, A.; Melfi, R.; Ussia, G.P.; Grigioni, F. Invasive Assessment of Coronary Microvascular Function. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 11, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, H.; Zheng, D.; Xia, L. Index of microcirculatory resistance: State-of-the-art and potential applications in computational simulation of coronary artery disease. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2022, 23, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fearon, W.F.; Kobayashi, Y. Invasive Assessment of the Coronary Microvasculature: The Index of Microcirculatory Resistance. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2017, 10, e005361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toya, T.; Nagatomo, Y.; Ikegami, Y.; Masaki, N.; Adachi, T. Coronary microvascular dysfunction in heart failure patients. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1153994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dryer, K.; Gajjar, M.; Narang, N.; Lee, M.; Paul, J.; Shah, A.P.; Nathan, S.; Butler, J.; Davidson, C.J.; Fearon, W.F.; et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018, 314, H1033–H1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirinos, J.A.; Mitchell, G.F.; Parise, H.; Benjamin, E.J.; Larson, M.G.; Keyes, M.J.; Vita, J.A.; Vasan, R.S.; Levy, D.; Hashimoto, J.; et al. Large Artery Stiffness, Microvascular Function, and Cardiovascular Risk. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 9, e005903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikonomidis, I.; Lekakis, J.; Papadopoulos, C.; Triantafyllidi, H.; Paraskevaidis, I.; Georgoula, G.; Tzortzis, S.; Revela, I.; Kremastinos, D.T. Incremental value of pulse wave velocity in the determination of coronary microcirculatory dysfunction in never-treated patients with essential hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 2008, 21, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakalidis, A.; Dimitriadis, K.; Leontsinis, I.; Dri, E.; Mantzouranis, E.; Bora, M.; E Karanikola, A.; Iliakis, P.; Vlachakis, P.; Siafi, E.; et al. Increased arterial stiffness in patients with ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery disease. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, ehad655.2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aursulesei Onofrei, V.; Ceasovschih, A.; Anghel, R.C.; Roca, M.; Marcu, D.T.M.; Adam, C.A.; Mitu, O.; Cumpat, C.; Mitu, F.; Crisan, A.; et al. Subendocardial Viability Ratio Predictive Value for Cardiovascular Risk in Hypertensive Patients. Medicina 2022, 59, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Wu, G.; Wang, S.; Huang, J. The prevalence of coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) in heart failure with pre-served ejection fraction (HFpEF): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’amario, D.; Migliaro, S.; Borovac, J.A.; Restivo, A.; Vergallo, R.; Galli, M.; Leone, A.M.; Montone, R.A.; Niccoli, G.; Aspromonte, N.; et al. Microvascular Dysfunction in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulus, W.J.; Zile, M.R. From Systemic Inflammation to Myocardial Fibrosis: The Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction Paradigm Revisited. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 1451–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagris, M.; Theofilis, P.; Antonopoulos, A.S.; Oikonomou, E.; Paschaliori, C.; Galiatsatos, N.; Tsioufis, K.; Tousoulis, D. Inflammation in Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanagala, P.; Arnold, J.R.; Singh, A.; Chan, D.C.S.; Cheng, A.S.H.; Khan, J.N.; Gulsin, G.S.; Yang, J.; Zhao, L.; Gupta, P.; et al. Characterizing heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction: An imaging and plasma biomarker approach. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornuault, L.; Rouault, P.; Duplàa, C.; Couffinhal, T.; Renault, M.-A. Endothelial Dysfunction in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: What are the Experimental Proofs? Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 906272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, M.C.; Lee, R.; Cascino, T.M.; Konerman, M.C.; Hummel, S.L. Current Perspectives on Systemic Hypertension in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2017, 19, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.-Y.M.; Lin, L.-Y.; Tseng, Y.-H.E.; Chang, C.-C.; Wu, C.-K.; Lin, J.-L.; Tseng, W.-Y.I. CMR-verified diffuse myocardial fibrosis is associated with diastolic dysfunction in HFpEF. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2014, 7, 991–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brann, A.; Miller, J.; Eshraghian, E.; Park, J.J.; Greenberg, B. Global longitudinal strain predicts clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2023, 25, 1755–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Chen, Q.; Ma, S. Left atrial fibrosis in atrial fibrillation: Mechanisms, clinical evaluation and management. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 2764–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauchier, L.; Bisson, A.; Bodin, A. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and atrial fibrillation: Recent advances and open questions. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorter, T.M.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Mulder, B.A.; Artola Arita, V.A.; van Empel, V.P.M.; Manintveld, O.C.; Tieleman, R.G.; Maass, A.H.; Vernooy, K.; van Gelder, I.C.; et al. Prevalence and Incidence of Atrial Fibrillation in Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction: (Additive) Value of Implantable Loop Recorders. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millan-Orge, M.; Torres-Peña, J.D.; Arenas-Larriva, A.; Quintana-Navarro, G.M.; Peña-Orihuela, P.; Alcala-Diaz, J.F.; Luque, R.M.; Rodriguez-Cantalejo, F.; Katsiki, N.; Lopez-Miranda, J.; et al. Influence of dietary intervention on microvascular endothelial function in coronary patients and atherothrombotic risk of recurrence. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Peña, J.D.; Rangel-Zuñiga, O.A.; Alcala-Diaz, J.F.; Lopez-Miranda, J.; Delgado-Lista, J. Mediterranean Diet and Endothelial Function: A Review of its Effects at Different Vascular Bed Levels. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindler, T.H.; Valenta, I. Coronary microvascular dysfunction and prognostication in diabetes mellitus. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2023, 24, 572–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, P.; Athanasiadis, A.; Sechtem, U. Pharmacotherapy for coronary microvascular dysfunction. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2015, 1, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelsen, M.M.; Rask, A.B.; Suhrs, E.; Raft, K.F.; Høst, N.; Prescott, E. Effect of ACE-inhibition on coronary microvascular function and symptoms in normotensive women with microvascular angina: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soleymani, M.; Masoudkabir, F.; Shabani, M.; Vasheghani-Farahani, A.; Behnoush, A.H.; Khalaji, A. Updates on Pharmacologic Management of Microvascular Angina. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2022, 2022, 6080258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K.T.; Sun, Y.; Gerling, I.C.; Guntaka, R.V. Regression of Established Cardiac Fibrosis in Hypertensive Heart Disease. Am. J. Hypertens. 2017, 30, 1049–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engholm, M.; Bertelsen, J.B.; Mathiassen, O.N.; Bøtker, H.E.; Vase, H.; Peters, C.D.; Bech, J.N.; Buus, N.H.; Schroeder, A.P.; Rickers, H.; et al. Effects of renal denervation on coronary flow reserve and forearm dilation capacity in patients with treatment-resistant hypertension. A randomized, double-blinded, sham-controlled clinical trial. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 250, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, H.; Hammer, P.; Olschewski, M.; Münzel, T.; Escaned, J.; Gori, T. Coronary Venous Pressure and Microvascular Hemodynamics in Patients with Microvascular Angina: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2023, 8, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelshiker, M.A.; Seligman, H.; Howard, J.P.; Rahman, H.; Foley, M.; Nowbar, A.N.; A Rajkumar, C.; Shun-Shin, M.J.; Ahmad, Y.; Sen, S.; et al. Coronary flow reserve and cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 1582–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorbala, S.; Di Carli, M.F. Cardiac PET perfusion: Prognosis, risk stratification, and clinical management. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2014, 44, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, V.L.; Naya, M.; Foster, C.R.; Hainer, J.; Gaber, M.; Di Carli, G.; Blankstein, R.; Dorbala, S.; Sitek, A.; Pencina, M.J.; et al. Improved cardiac risk assessment with noninvasive measures of coronary flow reserve. Circulation 2011, 124, 2215–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Lee, J.C.Y.; Leung, S.T.; Lai, A.; Lee, T.-F.; Chiang, J.B.; Cheng, Y.W.; Chan, H.-L.; Yiu, K.-H.; Goh, V.K.-M.; et al. Long-Term Prognosis of Patients with Coronary Microvascular Disease Using Stress Perfusion Cardiac Magnetic Resonance. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 14, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]