1. Introduction

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI), also known as mild neurocognitive disorder (mild NCD), is an intermediate state between normal cognition and dementia. It is characterized by a slight cognitive decline that does not have a significant impact on independence in daily activities [1]. While a substantial number of people with MCI maintain stability or revert to normal cognition over time (about 16% [2]), over half of them progress to dementia within five years [3]. To mitigate cognitive decline, individuals with MCI may turn to non-pharmacological interventions, such as cognitive interventions. These interventions are broadly categorized into three approaches: cognitive stimulation, cognitive training (CT), and cognitive rehabilitation [4]. More specifically, cognitive stimulation reflects mentally stimulating activities in which the patient participates to improve cognition and social functioning; conversely, CT is usually conceived as individual or group sessions aimed at enhancing specific cognitive functions such as memory or executive exercises through paper and pencil instruments or computerized tools. Finally, cognitive rehabilitation involves tailored interventions designed and implemented to recover cognitive abilities temporarily and partially lost and to address each patient’s key difficulties and goals [4]. Among these, CT has demonstrated the highest efficacy in enhancing cognition and improving psychosocial functioning in both healthy and clinical populations [5,6,7].

Specifically, CT involves structured practice on standardized cognitive tasks designed to enhance specific cognitive functions like memory, attention, or language [8,9]. These tasks can be administered individually or in group settings, using paper-and-pencil or computerized formats, and sometimes can simulate activities of daily life [10]. A fundamental assumption of CT is that practice can either improve, or, at least, maintain, functioning in the targeted cognitive domain, with effects extending beyond the training context [9].

Numerous studies have investigated the efficacy of CT in treating neuropsychological profiles in MCI using both unimodal (solely CT) and multimodal interventions (e.g., CT combined with physical fitness or drug treatment). These studies have reported significant enhancements in cognitive abilities and daily living skills among older individuals with MCI [10,11,12,13]. These interventions may have tapped into pre-existing cognitive reserves [14,15] and facilitated neuroplasticity in various brain regions, including the frontoparietal network and the hippocampus—a critical region for memory support [16,17]. However, the results of CT research have not always been consistent. While some studies have found clear benefits for trained ability, including both near and far effects on untrained abilities, other research has yielded little to no evidence of CT’s benefit. These disparities in findings may be attributed to heterogeneity in the design and methodological rigor of CT studies, limiting the understanding of the mechanisms of CT and its applicability to different populations [18].

Furthermore, previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses examining the efficacy of cognitive interventions in MCI have reported mixed results, e.g., [6,18,19]. These reviews have often failed to differentiate between various forms of interventions and training, the instruments used to measure outcomes, and the inclusion of a control group. To address these limitations found in the existing literature, the current meta-analysis aims to update and assess the efficacy of CT on specific neuropsychological test performances in individuals diagnosed with MCI, as compared to MCI control groups (i.e., individuals engaged in alternative training, like mental leisure activities and usual care) in randomized controlled trials (RCTs). We sought to address the following research questions: (i) which cognitive domains exhibit improvement after the application of CT in MCI?; and (ii) what are the effects of relevant demographic, clinical, and CT characteristics (e.g., duration and frequency of CT, type of CT) on the calculated effect sizes? Identifying the specific cognitive variables that improve following CT in MCI could provide valuable insights for enhancing the management and planning of potential cognitive remediation interventions aimed at preventing cognitive decline and the associated loss of functionality.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Registration

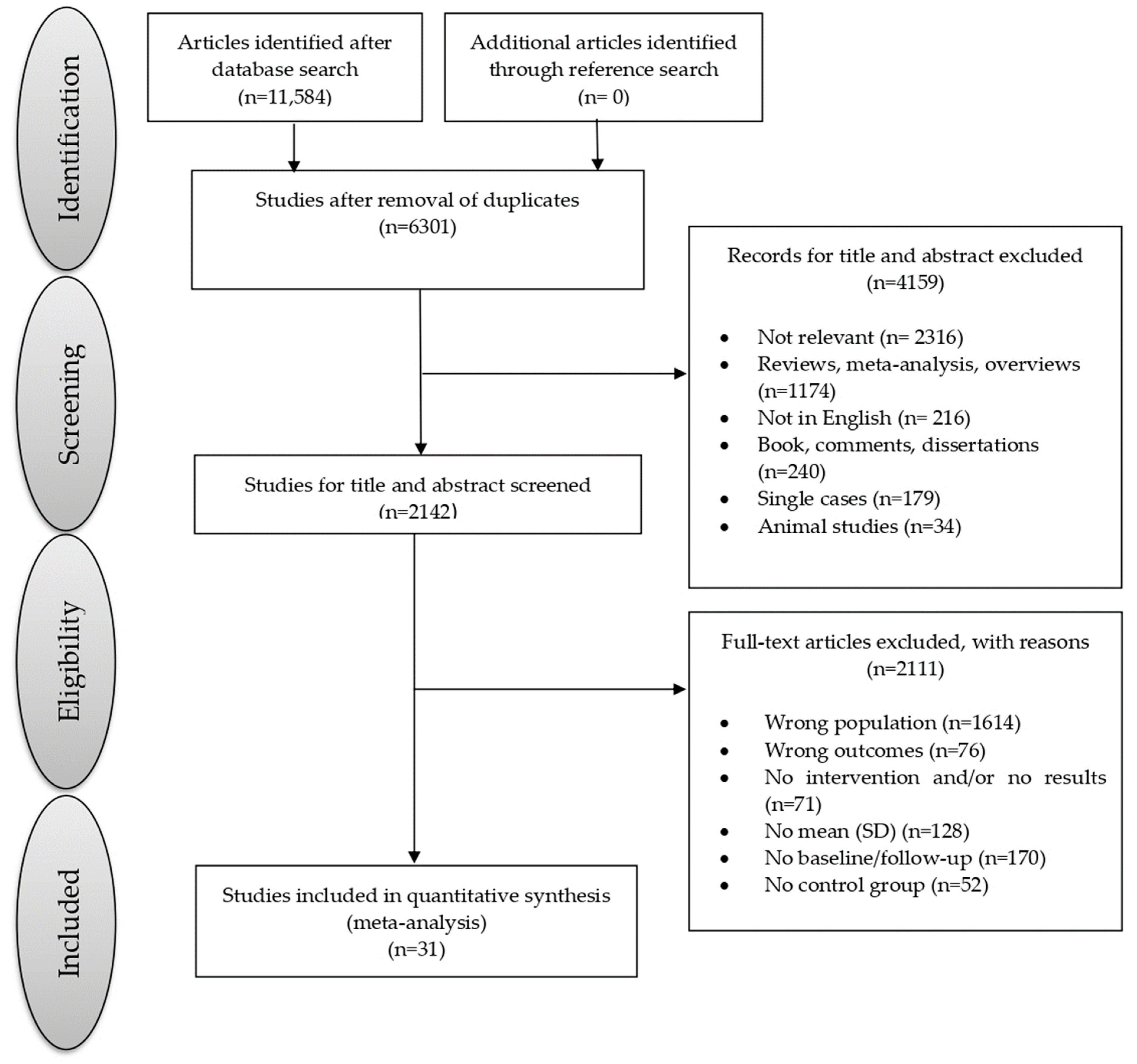

The current meta-analysis was preregistered electronically on the PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews under the registration number CRD42023421038. It was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [20,21]. The study selection process is visually represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the selection process of primary studies.

2.2. Data Sources and Study Selection

Article searches were comprehensively conducted on the PsycInfo (PROQUEST), PubMed, and Scopus databases. The search query utilized the term string: “cognitive training” AND (cognit* OR memory OR attention OR “executive function” OR Language) AND (MCI OR “mild cognitive impairment” OR “mild neurocognitive disorder”) AND (longitudinal OR “follow-up” OR outcomes OR predict*). The final date for the database searches was the end of March 2023. Peer-reviewed English studies that evaluated cognitive status in MCI were included if they met the following criteria: first, the study should compare individuals diagnosed with MCI or mild NCD undergoing CT against individuals diagnosed with MCI or mild NCD engaged in an alternative control training (e.g., active interventions like non-adaptive/non-tailored CT, educational activities on cognitive functions; or passive interventions like mental leisure activities or usual care); second, the study should assess cognitive functioning using a validated neuropsychological battery composed of recognized neuropsychological tests; third, the study should have provided adequate data (e.g., mean and median) to compute effect sizes for cognitive outcomes, both before and after the execution of the CT. The primary studies with the highest number of participants were selected when 2 or more studies provided data obtained from the same database [22].

2.3. Screening and Data Extraction

Article screening, data extraction, and quality evaluation were independently conducted by two investigators (SR and MC). The extracted information included: (i) publication characteristics; (ii) sample characteristics; (iii) CT characteristic; and (iv) means and standard deviations of raw scores or age- and education-adjusted scores, as reported in primary studies, for neuropsychological tests used to assess cognitive domains. To assess the overall external and internal validity and analysis of studies included in the meta-analysis, we calculated a quality score according to a modified version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale [23].

2.4. Outcomes

The outcomes assessed in this meta-analysis included: global cognitive functioning, memory, executive functions, and their subdomains (i.e., shifting, inhibition, generativity, and working memory), processing speed/attention, visuospatial abilities, and language. We categorized neuropsychological tasks into the aforementioned cognitive domains based on the indication provided by primary studies. To avoid higher levels of inter-study heterogeneity, we selected for each cognitive domain the most frequently utilized neuropsychological task from the primary studies, ensuring it was performed by the largest number of participants, serving as the outcome for the meta-analysis. A list of the neuropsychological tasks corresponding to each cognitive domain can be found in .

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted utilizing ProMeta 3.0 software (Intenovi 2015, Cesena, Italy). To achieve the primary objectives of the meta-analysis, we calculated effect sizes (ES) from the data reported in the primary studies using the Hedges unbiased approach [24]. Hedges’g-values were interpreted according to the following conventions: values < 0.20 indicated small effects, values around 0.50 suggested moderate effects, and values near 0.80 indicated large effects. Specifically, we examined the following comparisons of interest: (i) individuals with MCI involved in cognitive training (+CT) compared to those engaged in control training (−CT). Positive Hedges’ g-values indicated that individuals with MCI + CT scored higher than those with MCI − CT. Heterogeneity among the studies was evaluated using the Q and I2 statistics index [25]. We explored the impact of demographic and clinical characteristics (such as age, gender, years of education, and type of MCI), type of training (computerized or traditional), mode of training (unimodal or multimodal intervention), and duration of CT (intervention duration in weeks, session duration in minutes, and sessions per week), type of control group (i.e., passive or active), through several meta-regressions. The presence of publication bias was assessed using a scatter plot of estimated ES from individual studies against a measure of study precision (e.g., their standard errors [26]). To ensure a more robust funnel plot analysis, we utilized Egger’s regression method [27]. Furthermore, we employed the trim-and-fill procedure [28] to assess the potential impact of data censoring on the outcomes of the meta-analysis. According to this method, studies that introduce asymmetry in funnel plots are identified and adjusted, allowing for the overall effect estimate derived from the remaining studies to be minimally influenced by publication bias. A p-value of <0.05 was set as the cut-off for significance in all analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

A total of 11,584 studies were identified through the search process. After assessing the title and abstract, the full texts of these 31 studies were obtained, enrolling a cumulative total of 2496 individuals with MCI (mean age = 73.86 years, SD = 6.51 years; mean education = 10.92 years, SD = 3.18 years, 32.45% male). Specifically, of the 2496 individuals with MCI, 1310 participated in CT (mean age = 73.76 years, SD = 6.37 years; mean education = 11.01 years, SD = 3.04 years; 32.36% male; mean intervention duration = 12.11 weeks; mean session duration = 73.39 min; mean session for week = 2.28 times), while 1186 were included in a control training group (mean age = 73.97 years, SD = 6.66 years, mean education = 10.83 years, SD = 3.32 years, 32.54% male; mean intervention duration = 13.53 week; mean session duration = 60.41 min; mean session for week = 2.58 times). Details regarding the demographic and clinical characteristics of participants, as well as the type of training, are presented in . The table also provides results from the quality assessment based on the Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale; the quality scores of the included studies ranged from 6 to 10, indicating relatively high quality and, consequently, yielding reliable findings.

3.2. Meta-Analytic Results

3.3. Moderator Analysis

We found that the mode of CT moderated performance on task evaluating abstraction ability/concept formation. Specifically, the multimodal interventions of CT were associated with a higher performance (Q(1) = 6.49, p = 0.011). Neither the effects of other demographic, clinical, and CT variables (i.e., age, sex, years of education, type of MCI, type of control group, intervention duration in weeks, session duration in minutes, and session for a week) were statistically significant.

4. Discussion

The current meta-analysis provides new insights into the effectiveness of CT in MCI through a systematic exploration of studies that compared individuals with MCI + CT to those with MCI − CT on a comprehensive neuropsychological battery to identify the cognitive functions that improve after training. Its findings contribute to the existing literature in several significant ways. First, the results provide a detailed and precise comprehension of the cognitive functions influenced by CT in individuals with MCI. This specificity is crucial for tailoring interventions that target distinct cognitive deficits, potentially improving the overall quality of life for affected individuals [60]. Notably, moderate to high positive ES with statistical significance was found in verbal memory, generativity, working memory, and visuospatial abilities. However, no significant effects were found for abstraction ability/concept formation, processing speed, and language. The improvements on memory and visuospatial abilities domains are unsurprising given their central focus in most interventions and promising given this is the primary complaint in most cases of MCI [61]. Indeed, memory and visuospatial impairments are common and often debilitating in MCI, and the findings suggest that CT can effectively address memory-related difficulties [62]. Additionally, the improvement in working memory and generativity would suggest that CT would have positive effects also on higher-order cognitive abilities mediated by the frontal brain networks, and necessary to maintain independence in activities of daily living (ADL) and delaying dementia development.

These results partly differ from previous meta-analyses that found small to moderate effects on global cognitive functioning [63,64], attention, working memory, learning, and memory [63] after CT in people with MCI. These discrepancies could be due to the different inclusion criteria used in these studies, in particular, they considered only computerized CT and selected for each cognitive domain different types of neuropsychological tests while in the present study, we included computerized or traditional CT and identified the most frequently utilized neuropsychological task from the primary studies for each cognitive domain to avoid higher levels of inter-study heterogeneity.

On the other hand, the lack of effects on shifting and abstraction ability/concept formation might indicate that CT approaches employed in the meta-analysis included studies might not have effectively targeted these cognitive domains, with a lack of far transfer. This issue encourages clinicians to implement and refine CT specifically targeting these cognitive domains to have significant benefits [65,66]. In particular, we found that the type of intervention (unimodal or multimodal) moderated performance on task evaluating abstraction ability/concept formation with multimodal interventions (CT combined with physical exercise) resulted in being more effective in enhancing these abilities compared to interventions involving CT alone. These findings are in line with previous randomized control studies demonstrating that CT immediately preceded by aerobic exercise improved multiple cognitive processes due to the benefic effect of cortisol on learning and memory produced by moderate-intensity physical exercise [67,68]. Otherwise, no significant results were also found for processing speed and language abilities between individuals with MCI + CT and those with MCI − CT. However, the high heterogeneity in these results would suggest that the effectiveness of CT might vary across different studies and interventions. Moreover, the moderator effect of CT mode on abstraction ability/concept formation (i.e., the combined mode of CT was associated with higher performance in this cognitive domain) would encourage us to consider how different CT designs may play a role in their efficacy in certain cognitive domains within clinical setting [69,70].

Thus, the present meta-analyses updated the previous meta-analytic results [18,71], by reducing heterogeneity through the selection of widely used cognitive tests for each domain and considering executive functioning in its different subcomponents (i.e., generativity, abstraction ability/concept formation, working memory, and shifting). It also expands analysis to previously unexamined cognitive domains due to the limited number of primary studies. Nevertheless, this study is not without limitations. First, separate meta-analyses between amnestic and non-amnestic forms of MCI were not conducted. This might lead to significantly different effects among participants and make it difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of the CT and the generalizability of the current results. However, the selection of primary studies with established clear diagnostic criteria for MCI, and implementing RCTs reduced significantly the number of selected studies to perform a deeper analysis. Second, the lack of long-term follow-up made it unclear whether observed post-intervention benefits contributed to delaying or preventing progression from MCI to dementia. Moreover, we should underline that we did not explore the duration necessary to obtain long-term maintenance of benefits. However, although it has been proved that CT performed every week for one year approximately generated improvements in cognitive functions observed also 4 years after the end of the training, the duration seems to have a null on outcome measures [67]. Finally, we suggested taking the results of our meta-analyses with a limited number of studies (i.e., 2–4), with caution as heterogeneity cannot be reliably estimated and can happen a significant statistically moderate or high effect when combining few statistically significant studies with effects pointing into the same direction [72]. These limitations may be potentially overcome by more RCTs examining long-term cognitive outcomes to assess the transfer of CT to daily life and provide more insight into its impact on dementia progression.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the results from the meta-analysis provide valuable new insight into the efficacy of CT in MCI. By thoroughly examining cognitive domains and identifying specific functions that improve with training, this study offers guidance for the development of targeted and effective interventions to support individuals with MCI. The findings underscore the potential benefits of CT in enhancing cognitive functioning and quality of life within this population. Nevertheless, the study also highlights areas where further research and refinement of CT approaches are needed to effectively address certain cognitive deficits.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Koepsell, T.D.; Monsell, S.E. Reversion from mild cognitive impairment to normal or near-normal cognition: Risk factors and prognosis. Neurology 2012, 79, 1591–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, S.; Reisberg, B.; Zaudig, M.; Petersen, R.C.; Ritchie, K.; Broich, K.; Belleville, S.; Brodaty, H.; Bennett, D.; Chertkow, H.; et al. Mild cognitive impairment. Lancet 2006, 367, 1262–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, J.; Magalhaes, R.; Thomas, R.E.; Goncalves, O.F.; Petrosyan, A.; Sampaio, A. Is there evidence for cognitive intervention in Alzheimer disease? A systematic review of efficacy, feasibility, and cost-effectiveness. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2013, 27, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Abrahamson, K. Cognitive interventions for individuals with mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2016, 3, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, D.S.; Mauser, J.; Nuno, M. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive training using a visual speed of processing intervention in middle aged and older adults. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuli, C.; Fattoretti, P.; Lattanzio, F.; Balietti, M.; Di Stefano, G.; Solazzi, M. Cognitive rehabilitation in patients affected by mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clare, L.; Woods, R.T. Cognitive training and cognitive rehabilitation for people with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease: A review. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2003, 13, 293–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clare, L.; Woods, R.T. Cognitive training and cognitive rehabilitation for people with mild to moderate dementia of the Alzheimer’s or vascular type: A review. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2004, 14, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar-Fuchs, A.; Clare, L.; Woods, B. Cognitive training and cognitive rehabilitation for mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD003260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Clare, L.; Altgassen, A.M.; Cameron, M.H.; Zehnder, F. Cognition-based interventions for healthy older people and people with mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 1, CD006220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, S.S.; Yokomizo, J.E.; Bottino, C.M. Cognitive intervention in amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2012, 36, 1163–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.Y.; Tseng, H.Y.; Lin, Y.J.; Wang, C.J.; Hsu, W.C. Using virtual reality-based training to improve cognitive function, instrumental activities of daily living and neural efficiency in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2020, 56, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2012, 11, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirth, M.; Haase, C.M.; Villeneuve, S.; Vogel, J.; Jagust, W.J. Neuroprotective pathways: Lifestyle activity, brain pathology, and cognition in cognitively normal older adults. Neurobiol. Aging 2014, 35, 1873–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passow, S.; Thurm, F.; Li, S.C. Activating Developmental Reserve Capacity Via Cognitive Training or Non-invasive Brain Stimulation: Potentials for Promoting Fronto-Parietal and Hippocampal-Striatal Network Functions in Old Age. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutchess, A. Plasticity of the aging brain: New directions in cognitive neuroscience. Science 2014, 346, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huntley, J.; Bhome, R.; Holmes, B.; Cahill, J.; Gould, R.L.; Wang, H.; Yu, X.; Howard, R. Effect of computerised cognitive training on cognitive outcomes in mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reijnders, J.; van Heugten, C.; van Boxtel, M. Cognitive interventions in healthy older adults and people with mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2013, 12, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; The PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, G.; Raimo, S.; Cropano, M.; Vitale, C.; Barone, P.; Trojano, L. Neural bases of impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and an ALE meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. 2019, 107, 672–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modesti, P.A.; Reboldi, G.; Cappuccio, F.P.; Agyemang, C.; Remuzzi, G.; Rapi, S.; Perruolo, E.; Parati, G.; ESH Working Group on CV Risk in Low Resource Settings. Panethnic differences in blood pressure in Europe: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Huedo-Medina, T.B.; Sánchez-Meca, J.; Marín-Martínez, F.; Botella, J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol. Methods 2006, 11, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, H.R.; Sutton, A.J.; Borenstein, M. Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis: Prevention, Assessment and Adjustments; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Egger, M.; Smith, G.D.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, S.; Tweedie, R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 2000, 56, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balietti, M.; Giuli, C.; Fattoretti, P.; Fabbietti, P.; Postacchini, D.; Conti, F. Cognitive Stimulation Modulates Platelet Total Phospholipases A2 Activity in Subjects with Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016, 50, 957–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barban, F.; Annicchiarico, R.; Pantelopoulos, S.; Federici, A.; Perri, R.; Fadda, L.; Carlesimo, G.A.; Ricci, C.; Giuli, S.; Scalici, F.; et al. Protecting cognition from aging and Alzheimer’s disease: A computerized cognitive training combined with reminiscence therapy. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2016, 31, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretti, B.; Borella, E.; Fostinelli, S.; Zavagnin, M. Benefits of training working memory in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: Specific and transfer effects. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2013, 25, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yang, H.; Rooks, B.; Anthony, M.; Zhang, Z.; Tadin, D.; Heffner, K.L.; Lin, F.V. Autonomic flexibility reflects learning and associated neuroplasticity in old age. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2020, 41, 3608–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciarmiello, A.; Gaeta, M.C.; Benso, F.; Del Sette, M. FDG-PET in the Evaluation of Brain Metabolic Changes Induced by Cognitive Stimulation in aMCI Subjects. Curr. Radiopharm. 2015, 8, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnezan, L.C.; Perrot, A.; Belleville, S.; Bloch, F.; Kemoun, G. Effects of simultaneous aerobic and cognitive training on executive functions, cardiovascular fitness and functional abilities in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz Baquero, A.A.; Franco-Martín, M.A.; Parra Vidales, E.; Toribio-Guzmán, J.M.; Bueno-Aguado, Y.; Martínez Abad, F.; Perea Bartolomé, M.V.; Asl, A.M.; van der Roest, H.G. The Effectiveness of GRADIOR: A Neuropsychological Rehabilitation Program for People with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Mild Dementia. Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial After 4 and 12 Months of Treatment. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2022, 86, 711–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djabelkhir, L.; Wu, Y.H.; Vidal, J.S.; Cristancho-Lacroix, V.; Marlats, F.; Lenoir, H.; Carno, A.; Rigaud, A.S. Computerized cognitive stimulation and engagement programs in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: Comparing feasibility, acceptability, and cognitive and psychosocial effects. Clin. Interv. Aging 2017, 12, 1967–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duff, K.; Ying, J.; Suhrie, K.R.; Dalley, B.C.A.; Atkinson, T.J.; Porter, S.M.; Dixon, A.M.; Hammers, D.B.; Wolinsky, F.D. Computerized Cognitive Training in Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2022, 35, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiatarone Singh, M.A.; Gates, N.; Saigal, N.; Wilson, G.C.; Meiklejohn, J.; Brodaty, H.; Wen, W.; Singh, N.; Baune, B.T.; Suo, C.; et al. The Study of Mental and Resistance Training (SMART) study—Resistance training and/or cognitive training in mild cognitive impairment: A randomized, double-blind, double-sham controlled trial. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2014, 15, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, M.; McDonald, S. Repetition-lag training to improve recollection memory in older people with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. A randomized controlled trial. Neuropsychology, development, and cognition. Neuropsychol. Dev. Cogn. B Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2015, 22, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuli, C.; Papa, R.; Lattanzio, F.; Postacchini, D. The Effects of Cognitive Training for Elderly: Results from My Mind Project. Rejuvenation Res. 2016, 19, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenaway, M.C.; Duncan, N.L.; Smith, G.E. The memory support system for mild cognitive impairment: Randomized trial of a cognitive rehabilitation intervention. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 28, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagovská, M.; Olekszyová, Z. Impact of the combination of cognitive and balance training on gait, fear and risk of falling and quality of life in seniors with mild cognitive impairment. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2016, 16, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, C.; Chambon, C.; Michel, B.F.; Paban, V.; Alescio-Lautier, B. Positive effects of computer-based cognitive training in adults with mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychologia 2012, 50, 1871–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.F.; Flatt, J.D.; Fu, B.; Butters, M.A.; Chang, C.C.; Ganguli, M. Interactive video gaming compared with health education in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A feasibility study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2014, 29, 890–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyer, L.; Scott, C.; Atkinson, M.M.; Mullen, C.M.; Lee, A.; Johnson, A.; Mckenzie, L.C. Cognitive Training Program to Improve Working Memory in Older Adults with MCI. Clin. Gerontol. 2016, 39, 410–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.C.; Chan, W.C.; Leung, T.; Fung, A.W.; Leung, E.M. Would older adults with mild cognitive impairment adhere to and benefit from a structured lifestyle activity intervention to enhance cognition?: A cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, L.L.; Barnett, F.; Yau, M.K.; Gray, M.A. Effects of functional tasks exercise on older adults with cognitive impairment at risk of Alzheimer's disease: A randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 2014, 43, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Heffner, K.L.; Ren, P.; Tivarus, M.E.; Brasch, J.; Chen, D.G.; Mapstone, M.; Porsteinsson, A.P.; Tadin, D. Cognitive and Neural Effects of Vision-Based Speed-of-Processing Training in Older Adults with Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Pilot Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 1293–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavros, Y.; Gates, N.; Wilson, G.C.; Jain, N.; Meiklejohn, J.; Brodaty, H.; Wen, W.; Singh, N.; Baune, B.T.; Suo, C.; et al. Mediation of Cognitive Function Improvements by Strength Gains After Resistance Training in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: Outcomes of the Study of Mental and Resistance Training. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 63, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nousia, A.; Martzoukou, M.; Siokas, V.; Aretouli, E.; Aloizou, A.M.; Folia, V.; Peristeri, E.; Messinis, L.; Nasios, G.; Dardiotis, E. Beneficial effect of computer-based multidomain cognitive training in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2021, 28, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olchik, M.R.; Farina, J.; Steibel, N.; Teixeira, A.R.; Yassuda, M.S. Memory training (MT) in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) generates change in cognitive performance. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2013, 56, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poptsi, E.; Tsatali, M.; Agogiatou, C.; Bakoglidou, E.; Batsila, G.; Dellaporta, D.; Kounti-Zafeiropoulou, F.; Liapi, D.; Lysitsas, K.; Markou, N.; et al. Longitudinal Cognitive and Physical Training Effectiveness in MCI, Based on the Experience of the Alzheimer's Hellas Day Care Centre. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2022, 35, 512–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapp, S.; Brenes, G.; Marsh, A.P. Memory enhancement training for older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A preliminary study. Aging Ment. Health 2002, 6, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, G.J.; Villar, V.; Iturry, M.; Harris, P.; Serrano, C.M.; Herrera, J.A.; Allegri, R.F. Efficacy of a cognitive intervention program in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2013, 25, 825–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitter-Edgecombe, M.; Dyck, D.G. Cognitive rehabilitation multi-family group intervention for individuals with mild cognitive impairment and their care-partners. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2014, 20, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savulich, G.; Piercy, T.; Fox, C.; Suckling, J.; Rowe, J.B.; O'Brien, J.T.; Sahakian, B.J. Cognitive Training Using a Novel Memory Game on an iPad in Patients with Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment (aMCI). Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017, 20, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukontapol, C.; Kemsen, S.; Chansirikarn, S.; Nakawiro, D.; Kuha, O.; Taemeeyapradit, U. The effectiveness of a cognitive training program in people with mild cognitive impairment: A study in urban community. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2021, 35, 18–23, Erratum in Asian J. Psychiatr. 2021, 55, 102000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolaki, M.; Kounti, F.; Agogiatou, C.; Poptsi, E.; Bakoglidou, E.; Zafeiropoulou, M.; Soumbourou, A.; Nikolaidou, E.; Batsila, G.; Siambani, A.; et al. Effectiveness of nonpharmacological approaches in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Neurodegener Dis. 2011, 8, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, W.; Liang, J.; Xue, J.; Zhu, T.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, S. The Transfer Effects of Cognitive Training on Working Memory Among Chinese Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimo, S.; Trojano, L.; Siciliano, M.; Cuoco, S.; D'Iorio, A.; Santangelo, F.; Abbamonte, L.; Grossi, D.; Santangelo, G. Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the multifactorial memory questionnaire for adults and the elderly. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 37, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega, J.N.; Newhouse, P.A. Mild cognitive impairment: Diagnosis, longitudinal course, and emerging treatments. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2014, 16, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar-Fuchs, A.; Martyr, A.; Goh, A.M.; Sabates, J.; Clare, L. Cognitive training for people with mild to moderate dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 3, CD013069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, N.T.; Mowszowski, L.; Naismith, S.L.; Chadwick, V.L.; Valenzuela, M.; Lampit, A. Computerized Cognitive Training in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2017, 174, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, N.J.; Vernooij, R.W.; Di Nisio, M.; Karim, S.; March, E.; Martínez, G.; Rutjes, A.W. Computerised cognitive training for preventing dementia in people with mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 3, CD012279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgeta, V.; McDonald, K.R.; Poliakoff, E.; Hindle, J.V.; Clare, L.; Leroi, I. Cognitive training interventions for dementia and mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2, CD011961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbo, I.; Casagrande, M. Higher-Level Executive Functions in Healthy Elderly and Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubert, C.; Chainay, H. Aging brain: The effect of combined cognitive and physical training on cognition as compared to cognitive and physical training alone—A systematic review. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 1267–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten Brinke, L.F.; Best, J.R.; Chan, J.L.C.; Ghag, C.; Erickson, K.I.; Handy, T.C.; Liu-Ambrose, T. The Effects of Computerized Cognitive Training with and Without Physical Exercise on Cognitive Function in Older Adults: An 8-Week Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2020, 75, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karssemeijer, E.G.A.; Aaronson, J.A.; Bossers, W.J.; Smits, T.; Olde Rikkert, M.G.M.; Kessels, R.P.C. Positive effects of combined cognitive and physical exercise training on cognitive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment or dementia: A meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 40, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanmore, E.; Stubbs, B.; Vancampfort, D.; de Bruin, E.D.; Firth, J. The effect of active video games on cognitive functioning in clinical and non-clinical populations: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 78, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, D.S.; Mauser, J.; Nuno, M.; Sherzai, D. The Efficacy of Cognitive Intervention in Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI): A Meta-Analysis of Outcomes on Neuropsychological Measures. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2017, 27, 440–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonnermann, A.; Framke, T.; Großhennig, A.; Koch, A. No solution yet for combining two independent studies in the presence of heterogeneity. Stat. Med. 2011, 34, 2476–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]