1. Introduction

Saffron, which is widely used in foods, cosmetic ingredients, and phytopharmaceuticals, is extracted from the dried stigmas of Crocus sativus L., which belongs to the family Iridaceae [1,2,3,4]. Saffron is used in both folk and modern medicines [5,6,7,8]. Crocin is one of the major bioactive constituents of saffron that is favored for oral administration owing to its water-solubility, safety, and lack of toxicity or side effects [9,10,11]. Crocin is converted into its active metabolite, crocetin (CRT), in the intestine after oral administration to exert pharmacological effects [12]. The direct administration of CRT can potentially yield improved pharmacological effects.

CRT, extracted and separated from the stigmas of C. sastivus [13,14], exhibits several pharmacological activities, such as anti-tumor, heart protection, memory enhancement, anti-anxiety, and anti-depression activities, and is effective against Alzheimer’s disease, myocardial ischemia, and coronary heart diseases [15,16,17]. CRT has two isomers—cis and trans—and its pharmacological efficacy is attributed primarily to the trans-isomer [18]. However, CRT is sensitive to heat, light, and pH and is insoluble in water and most organic solvents [19]. It partially dissolves in pyridine, dimethyl sulfoxide, and alkaline aqueous solutions above pH 9.0 [20]. Poor stability and solubility are major obstacles in its formulation and limit the pharmaceutical applications of CRT. Most formulation methods use solvents to encapsulate drugs; however, for CRT, suitable encapsulation formulations and preparation methods are extremely limited. In addition, improving the water solubility and bioavailability of CRT is crucial for maximum pharmacological efficacy. Several reports have evaluated various delivery approaches for CRT, including nanoliposomes, microencapsulation, and lipid nanoparticles; however, few studies have focused on improving the stability, water solubility, and bioavailability of CRT [21,22,23]. Li et al. used β-cyclodextrin-based nanosponges to improve the solubility of CRT, obtaining an elevated aqueous solubility of 7.27 ± 1.11 μg/mL [24]. Wong et al. developed an effective method to prepare CRT–γ-CD inclusion complexes (ICs) with enhanced CRT bioavailability and pharmacological effects against Alzheimer’s disease after intravenous injection; however, the authors did not describe the oral bioavailability of CRT [25]. Research aimed at improving the storage stability and oral bioavailability of CRT remains lacking.

Cyclodextrin (CD) is an effective drug carrier for CRT [24,25] with a wide range of applications in the agrochemical, pharmaceutical, fragrance, and food industries owing to its complexation ability and other versatile characteristics [26,27]. In addition to naturally occurring CDs (α, β, and γ-CD), modified CDs, including HP-β-CD, RM-β-CD, and SBE-β-CD, have attracted substantial attention in the pharmaceutical industry [28,29]. CDs are commonly used to enhance the water solubility, bioavailability, and stability of guest molecules while maintaining their pharmacological properties after forming ICs [30]. Moreover, CDs can mask the pungent odor and bitterness of drugs, making them ideal for the development of pharmaceutics and healthy food products.

Oral administration has several advantages over other routes, including the lack of damage to the skin or mucous membranes, low cost, and convenient storage. In addition, orally administered drugs are better tolerated by patients. Aiming to increase the oral bioavailability of CRT, this study used a trans-isomer of CRT along with two natural CDs (α and γ-CD) and a modified CD (HP-β-CD) to prepare three solid CRT/CD ICs using sonication and freeze-drying. The ICs were characterized based on the molecular states of each component. In addition, the water solubility, storage stability, and oral bioavailability of the CRT inclusion complex were investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

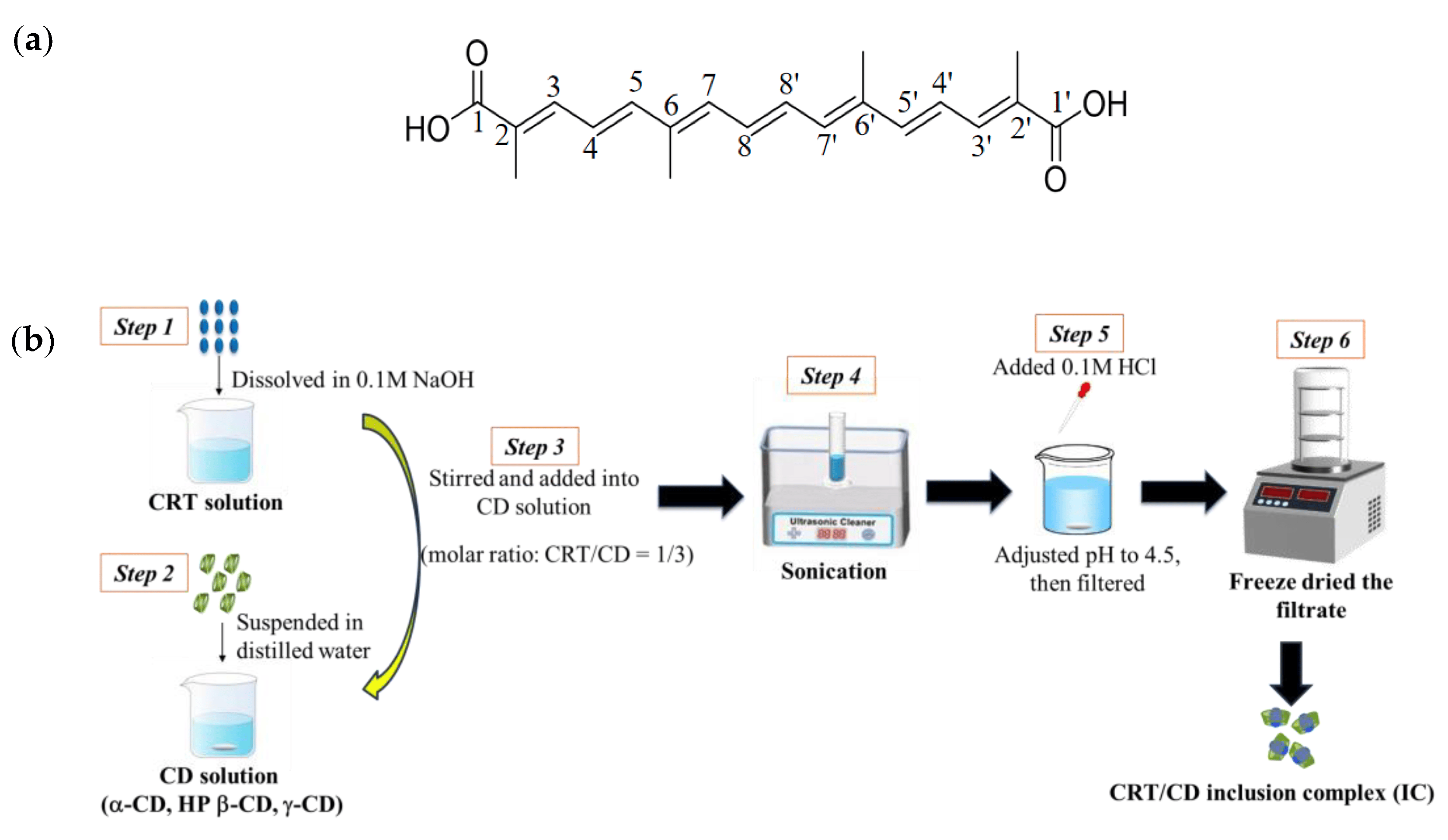

The trans-isomer of CRT (≥98%) was obtained from saffron and purified in our laboratory using an alkaline hydrolysis via response surface methodology, as previously described [31]. α-CD, HP-β-CD, and γ-CD were purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All chemicals and solvents used in this study were of analytical grade. The chemical structure of CRT is presented in Figure 1a.

Figure 1. (a) Chemical structure of crocetin (CRT). (b) Schematic processes for preparing CRT/CD inclusion complex (IC).

2.2. Animals

Male Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats (weighing 180–220 g) were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Center of Shenyang Pharmaceutical University (Shenyang, China).

2.3. Preparation of CRT/CD Inclusion Complexes

An outline of sample preparation processes is illustrated in Figure 1b. CRT was dissolved into 0.1 M NaOH to make the CRT solution. Each CD sample was suspended in distilled water. Next, the CRT solution was added dropwise to each aqueous CD solution with a molar ratio of CRT to CD of 1:3 for all CDs (α-, HP-β-, and γ-CD). All mixed solutions were sonicated for 3 h and supplemented with 0.1 M HCl to adjust the pH to 4.5. The mixed solutions were filtered through a 0.22 μM microporous filter membrane. The filtrate was freeze-dried to obtain solid CRT/CD ICs. CRT concentrations in ICs were assayed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) at a detection wavelength of 424 nm. The encapsulation efficiency (EE) of CRT was calculated using the following equation:

The EEs for CRT/α-CD IC, CRT/HP-β-CD, and CRT/γ-CD IC were 89.20 ± 0.43%, 89.93 ± 0.57%, and 91.90 ± 0.39%, respectively .

CRT was mixed with each CD (α-CD, HP-β-CD, and γ-CD) for 3 min using a vortex mixer with molar ratios of 1:3 to obtain the CRT/CD physical mixtures (PMs).

2.4. Characterization of CRT/CD ICs

2.5. Phase Solubility Study

The phase solubility of CRT was evaluated according to the method reported by Higuchi and Connors [32]. An excess of the drug (5 mg) was added to 10 mL of phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) with various concentrations of α-CD, HP-β-CD, and γ-CD (0–500 mM) in 25 mL stoppered conical flasks, which were shaken at 37 ± 0.5 °C for 72 h to reach equilibrium. The excess drug was removed via filtration using a 0.22 μM microporous filter membrane, and the drug concentrations were analyzed using HPLC. The assay was performed in triplicate for each CRT/CD system. The amount of CRT dissolved was plotted against the molar concentration of CDs, and assuming 1:1 complex formation, the apparent stability constant Kc was calculated from phase solubility diagrams using the following equation:

2.6. HPLC Analysis (Excluding Pharmacokinetics Study)

Each sample was analyzed using a Waters HPLC system consisting of a 2695–2487 UV detector (Milford, MA, USA). The analysis was carried out on a COSMOSIL-C18 (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) column. The mobile phase was a 15:85 (v/v%) mixture of 3.33% glacial acetic acid aqueous solution and methanol. The flow rate was 1.0 mL/min, the detection wavelength was 424 nm, and the injection volume was 10 μL.

2.7. Dissolution Test

The dissolution of CRT, PMs, and ICs was evaluated using the USP (version 26) paddle method with a dissolution tester (Tianjin University Electronics Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China). The dissolution medium was phosphate buffer (pH 6.8, 900 mL); the paddles were rotated at 100 rpm at 37.0 ± 0.5 °C. A sample volume of 5 mL was withdrawn from the dissolution medium at predetermined sampling points, filtered using a 0.22 μM microporous filter membrane, and analyzed via HPLC. All dissolution tests were performed in triplicate.

2.8. Solubility Determination

Drug solubility at 25 ± 0.5 °C was determined in water and phosphate buffer (pH 6.8). Excesses of CRT and each IC were added to each fluid and placed in a thermostatic water bath in the dark at 25 ± 0.5 °C with a constant shaking rate of 100 rpm for 72 h. After the equilibrium state was reached, the solutions were centrifuged for 15 min, and 2 mL of the supernatant was diluted with an appropriate amount of methanol. Drug concentrations were determined using HPLC.

2.9. Effect of Storage on Stability

All samples were sealed in transparent glass bottles and divided into three groups, each containing CRT/α-CD IC (500 mg), CRT/HP-β-CD IC (500 mg), CRT/γ-CD IC (500 mg), and intact CRT (500 mg). The first group was stored at 60 ± 0.5 °C for 10 days. The second group was stored at 25 ± 0.5 °C with a light intensity of 4500 ± 500 lx for 10 days. The third group was stored at 25 ± 0.5 °C with 75% relative humidity for 10 days. The CRT contents were sampled and measured on days 0, 5, and 10. Each test was repeated at least three times.

2.10. Pharmacokinetics Study

Twenty-four SD rats were randomly divided into four groups and administered CRT/α-CD IC, CRT/HP-β-CD IC, CRT/γ-CD IC, or intact CRT. All rats were fasted for 12 h and only provided water before experiments. All samples at a dose of 20 mg/kg body weight were administered intragastrically. Blood samples (0.4 mL) were collected from the orbital venous plexus at predetermined time points (0.083, 0.167, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h) into tubes containing heparin sodium. The blood samples were centrifuged immediately at 4000 rpm for 15 min; the supernatant layer of plasma was separated and stored at 4 °C for 24 h. CRT in plasma was extracted with 600 μL methanol with an internal standard of 10 μL ATRA from 200 μL plasma samples and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant layer was transferred to a new tube, concentrated to remove solvents under the LSE-1K vacuum centrifuge concentrator (JTLIANGYOU, Changzhou, China), and redissolved in 200 μL of methanol for analysis. The concentration of CRT was determined using an HPLC (Waters HPLC system consisting of a 2695–2487 UV detector, Milford, MA, USA) using a COSMOSIL-C18 (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) column with a detection wavelength of 424 nm. The injection volume was 20 μL, the column temperature was 35 °C, the mobile phase was methanol with water and glacial acetic acid in a ratio (v:v:v) of 92:7.7:0.3, and the flow rate was 1 mL/min. The pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using DAS 2.0. Relative bioavailability percentage was calculated as follows [33]:

2.11. Statistical Analysis

All results are presented as means ± standard deviation. Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance was used to evaluate significance.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of CRT/CD IC

3.2. Phase Solubility Study

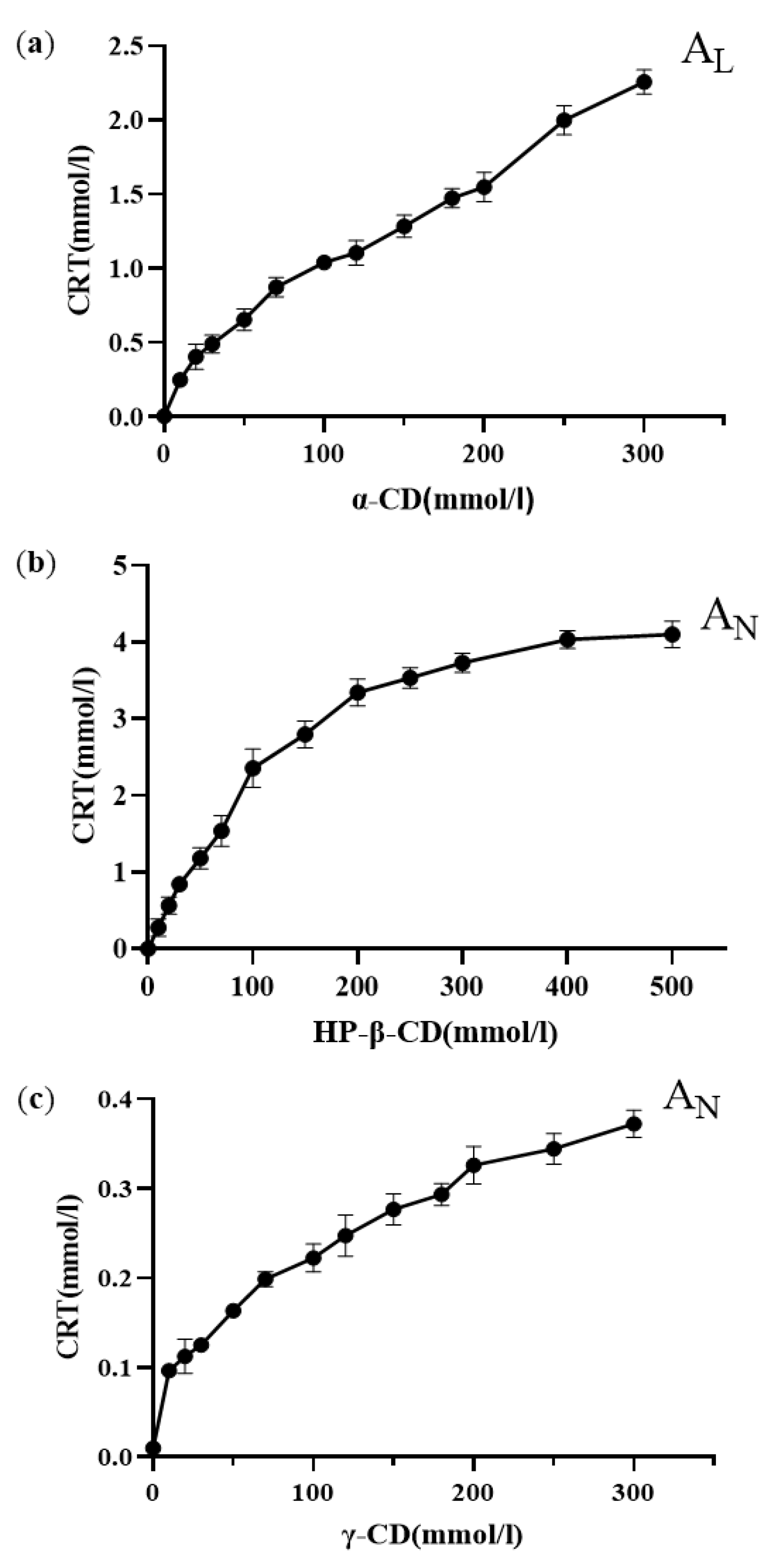

The phase solubility curves of CRT in α-CD, HP-β-CD, and γ-CD at 37 ± 0.5 °C in phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) are shown in Figure 6a–c. The solubility of CRT increased linearly as the CD concentration increased for α-CD, whereas the solubility of CRT in HP-β-CD and γ-CD increased nonlinearly and deviated from the straight line in the negative direction as the CD concentrations increased. This indicated that soluble ICs formed for all three types of CDs. According to the Higuchi and Connors classification [32], these diagrams could be classified as AL-type (linear increase in drug solubility as a function of cyclodextrin concentration) for α-CD and AN-type (negatively deviating isotherm) for HP-β-CD and γ-CD [53]. It was speculated that the inclusion ratios of CRT to CD may be 1:1 for α-CD and 1:2 for both HP-β-CD and γ-CD. Combined with the results of 1H NMR, changes in the chemical shifts of H3 and H5 for CRT/α-CD IC were relatively small; thus, CRT was only partially incorporated in α-CD, and the drug did not fully penetrate into its cavity. As listed in , the ΔG values of the three ICs were all negative, indicating that the inclusion reactions occur spontaneously. Based on the initial linear part of the profile, the stability constants (Kc) were 3027, 7912, and 427 M−1 for α-CD, HP-β-CD, and γ-CD, respectively . The stability constant of the IC formed between CRT and HP-β-CD was higher than that of the IC formed with the other two CDs, indicating that the IC formed between CRT and HP-β-CD was more stable, which could be due to the greater water solubility and higher wetting and complexing ability of HP-β-CD. The Kc of the CRT/γ-CD IC was lower than those of the other two ICs, possibly because γ-CD exhibits a larger pore size and CRT was more likely to dissociate from the CD cavity, resulting in the lowest stability among the ICs [49]. As determined using the continuous variation method [54] , the inclusion ratios were 1:1 for CRT/α-CD IC and 1:2 for both CRT/HP-β-CD and CRT/γ-CD ICs, consistent with the phase solubility results.

Figure 6. Phase solubility diagrams of (a) CRT/α-CD IC, (b) CRT/HP-β-CD IC, and (c) CRT/γ-CD IC (n = 3, mean ± S.D.).

3.3. Dissolution and Solubility of CRT/CD ICs

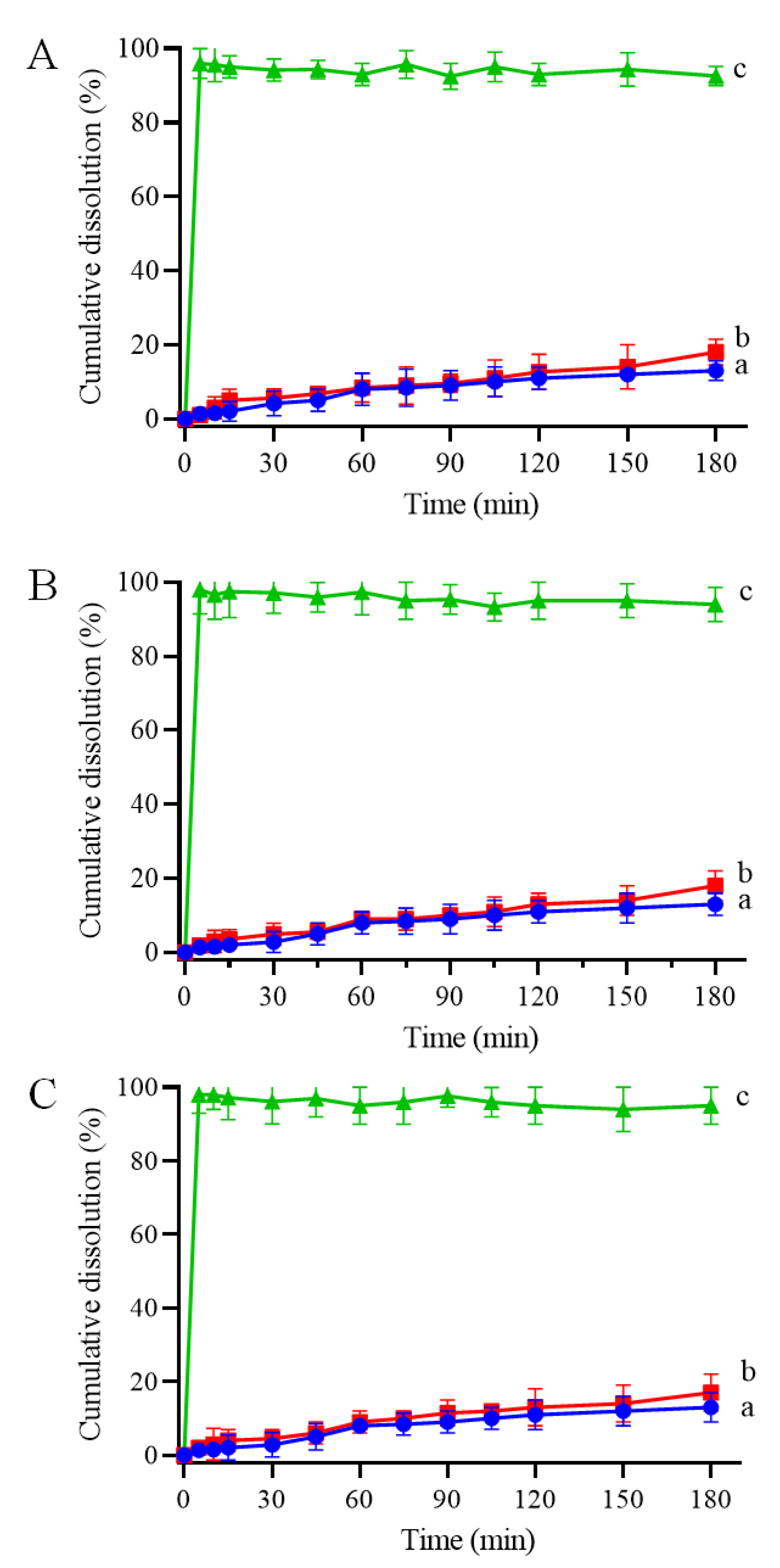

CRT is insoluble in water and most organic solvents; therefore, to determine whether the IC formation improves its dissolution behavior, dissolution properties in phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) were investigated. The CRT dissolution profiles of crystalline CRT, PMs, and ICs of CRT/α-CD, CRT/HP-β-CD, and CRT/γ-CD systems are shown in Figure 7A–C, respectively. The cumulative dissolution rate of crystalline CRT was only 13% at 180 min. Additionally, the dissolution rate of the PMs did not differ substantially from that of crystalline CRT, and the cumulative dissolution rates were 16, 18, and 19% at 180 min for CRT/α-CD, CRT/HP-β-CD, and CRT/γ-CD, respectively. The dissolution rates for both crystalline CRT and PMs were extremely low. Conversely, the cumulative dissolution of CRT from CRT/CD ICs at a sampling time of 5 min was approximately 97%, demonstrating much higher dissolution rates than those of PMs and crystalline CRT. The better solubility of CRT observed in 1H NMR and phase solubility studies might explain the fast dissolution of CRT/CD ICs (Figure 5 and Figure 6). In addition, the improvement in dissolution could be largely attributed to the amorphization of CRT after complexation, as indicated by the PXRD results (Figure 3). Solubility tests were performed to compare CRT/CD ICs and pure CRT. The solubility values of the prepared ICs with different CDs are listed in . The solubilities of pure CRT in water (1.23 ± 0.07 mg/L) and buffer salts (1.84 ± 0.11 mg/L) were extremely low. The solubility of CRT after forming ICs increased by approximately 6500–10,000 times . Notably, the best solubility was observed for CRT/HP-β-CD IC, possibly because HP-β-CD, a modified CD, has the best water solubility among the three CDs. Overall, all three CRT/CD ICs conferred an enhanced CRT dissolution rate and solubility, revealing their potential use in the development of effective strategies to enhance the dissolution rate of poorly water-soluble CRT.

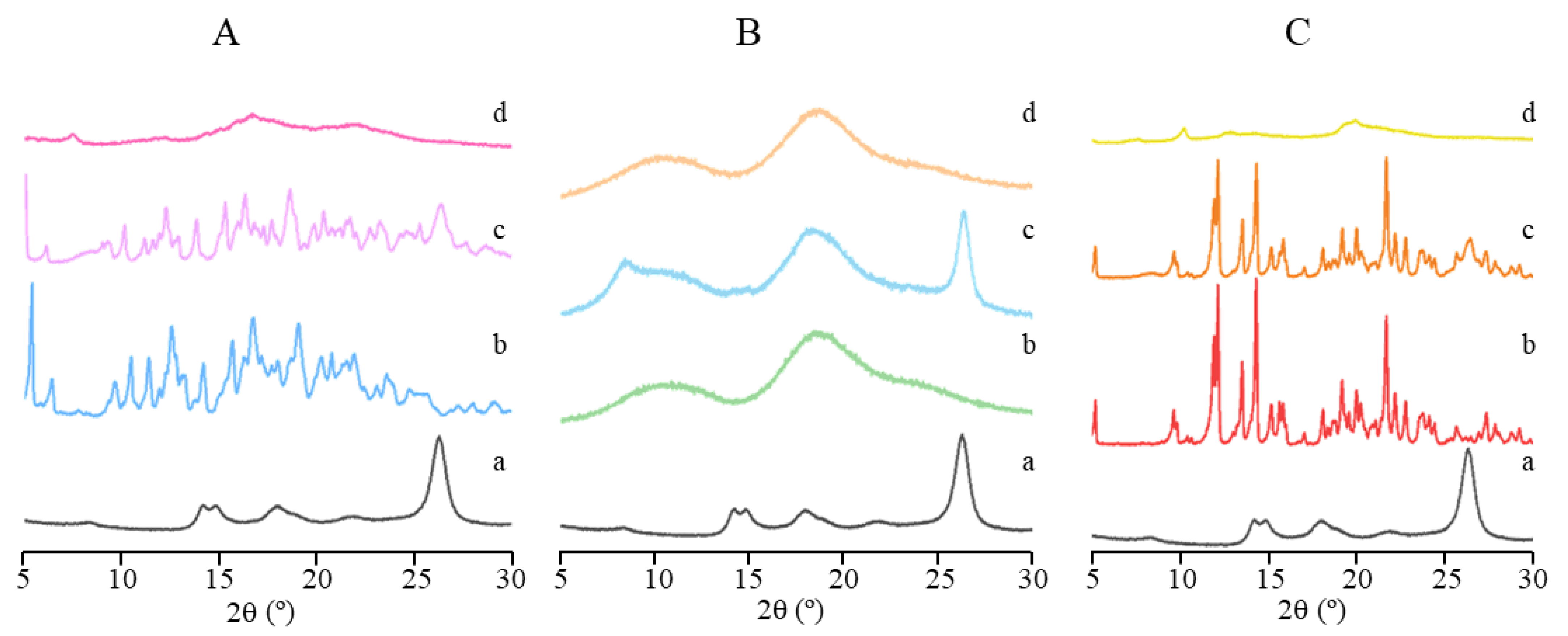

Figure 3. PXRD patterns of (a) CRT, (b) CD, (c) PM, and (d) IC in CRT/α-CD (A), CRT/HP-β-CD (B), and CRT/γ-CD (C) systems.

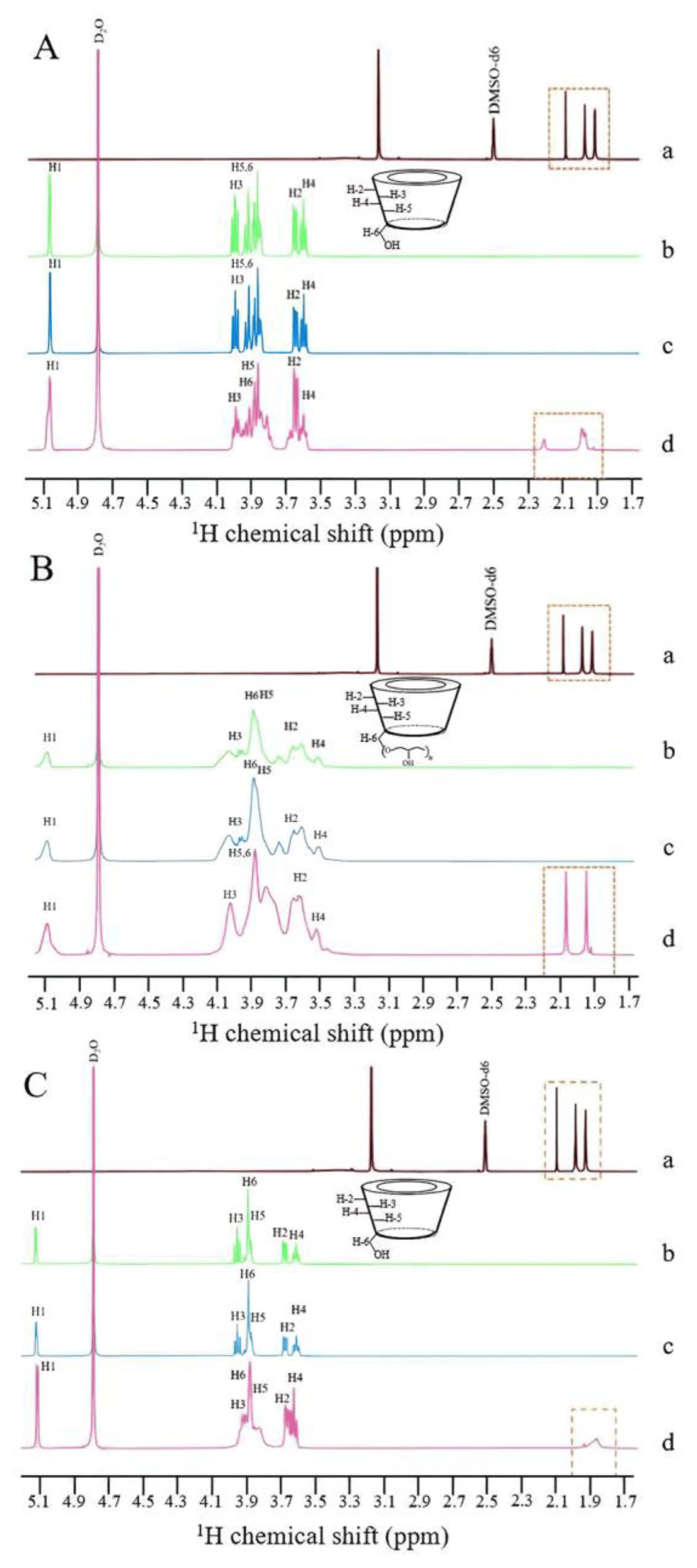

Figure 5. 1H NMR spectra of (a) CRT (DMSO-d6), (b) CD (D2O), (c) PM (D2O), and (d) IC (D2O) in CRT/α-CD (A), CRT/HP-β-CD (B), and CRT/γ-CD (C) systems from 1.7 to 5.1 ppm.

Figure 7. Dissolution profiles of (a) CRT, (b) PM, and (c) IC in CRT/α-CD (A), CRT/HP-β-CD system (B), and CRT/γ-CD (C) systems in phosphate-buffered solution at 37 °C and pH 6.8 (n = 3, mean ± S.D.).

3.4. Effect of Storage on the Stability of CRT

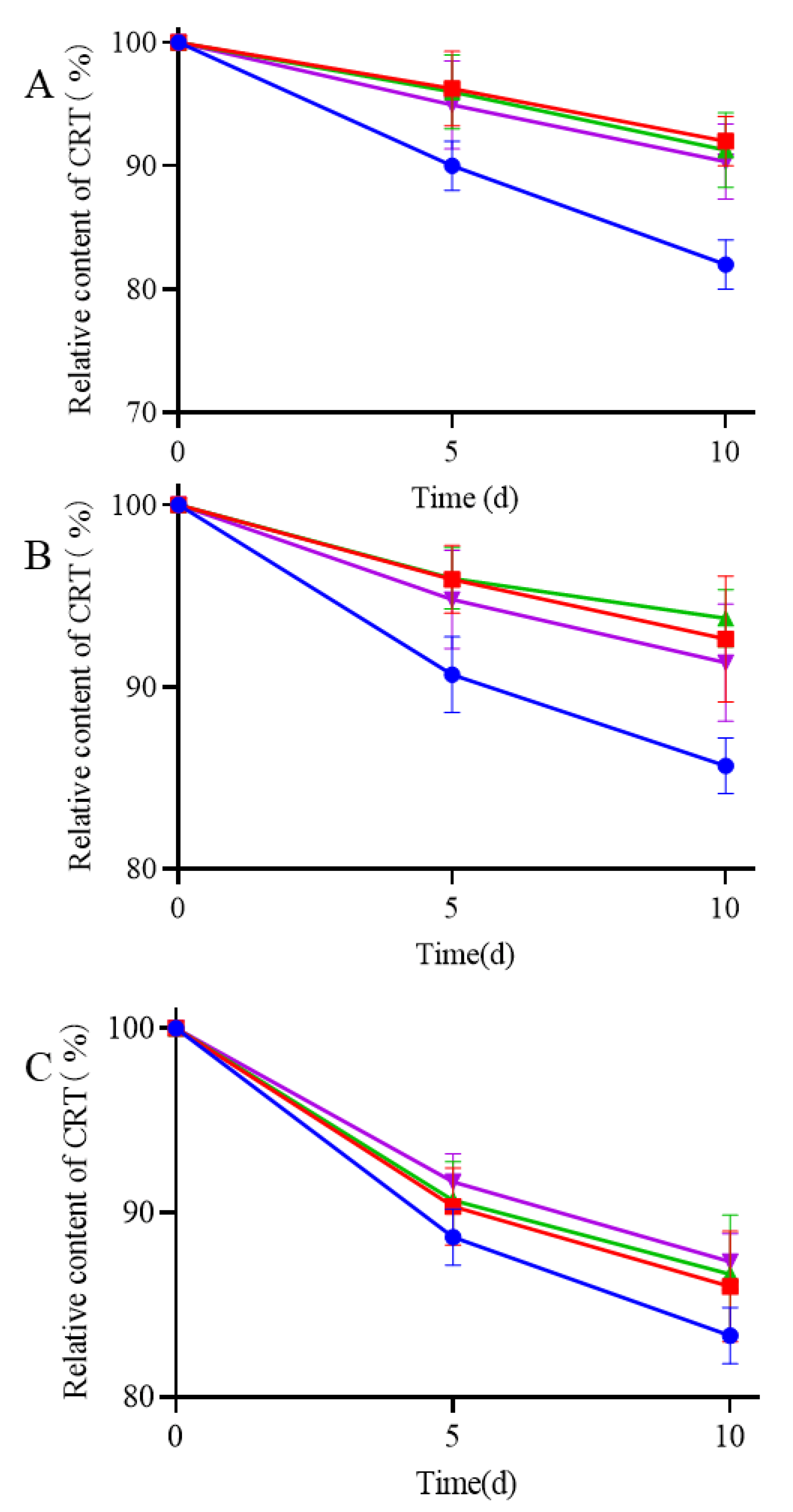

Stability was evaluated under various heat, light, and moisture conditions to investigate the effect of storage on the CRT content. The degradation curves of all samples (pure CRT, CRT/α-CD IC, CRT/HP-β-CD IC, and CRT/γ-CD IC) were determined by plotting the relative CRT content versus storage time (days) under different conditions. The storage conditions under heat, light, and moisture treatments are shown in Figure 8A–C. The relative contents of CRT and three types of ICs decreased to varying extents under all storage conditions. During thermal treatment (60 ± 0.5 °C) of CRT, the relative content of pure CRT significantly decreased to 80%, whereas ICs exhibited at least 90% retention even after 10 days. The preparation of ICs can significantly mitigate the decrease in CRT and improve thermal instability. During storage at a light intensity of 4500 ± 500 lx at 25 °C, the retention of CRT in ICs was at least 85%, slightly higher than that of pure CRT, indicating that ICs had greater stability than that of pure CRT under light conditions. During storage at an RH of 75% at 25 °C, the retention of both pure CRT and ICs decreased, although the decrease was slightly lower for ICs than pure CRT. CD may be a hydrophilic excipient that exhibits hygroscopicity under highly humid conditions. The encapsulation of water molecules affected the interaction between CD and CRT, resulting in a decrease in CRT contents in ICs [55]. During storage, CRT was degraded under heat, light, and moisture, whereas the formation of ICs could protect CRT from damage caused by these factors.

Figure 8. Stability experiments of (●) CRT, (■) CRT/α-CD IC, (▲) CRT/HP-β-CD IC, and (▼) CRT/γ-CD IC at 60 ± 0.5 °C (A), light intensity of 4500 ± 500 lx under 25 ± 0.5 °C (B), and 75% relative humidity conditions under 25 ± 0.5 °C (C).

3.5. Pharmacokinetics Study of CRT/CD ICs

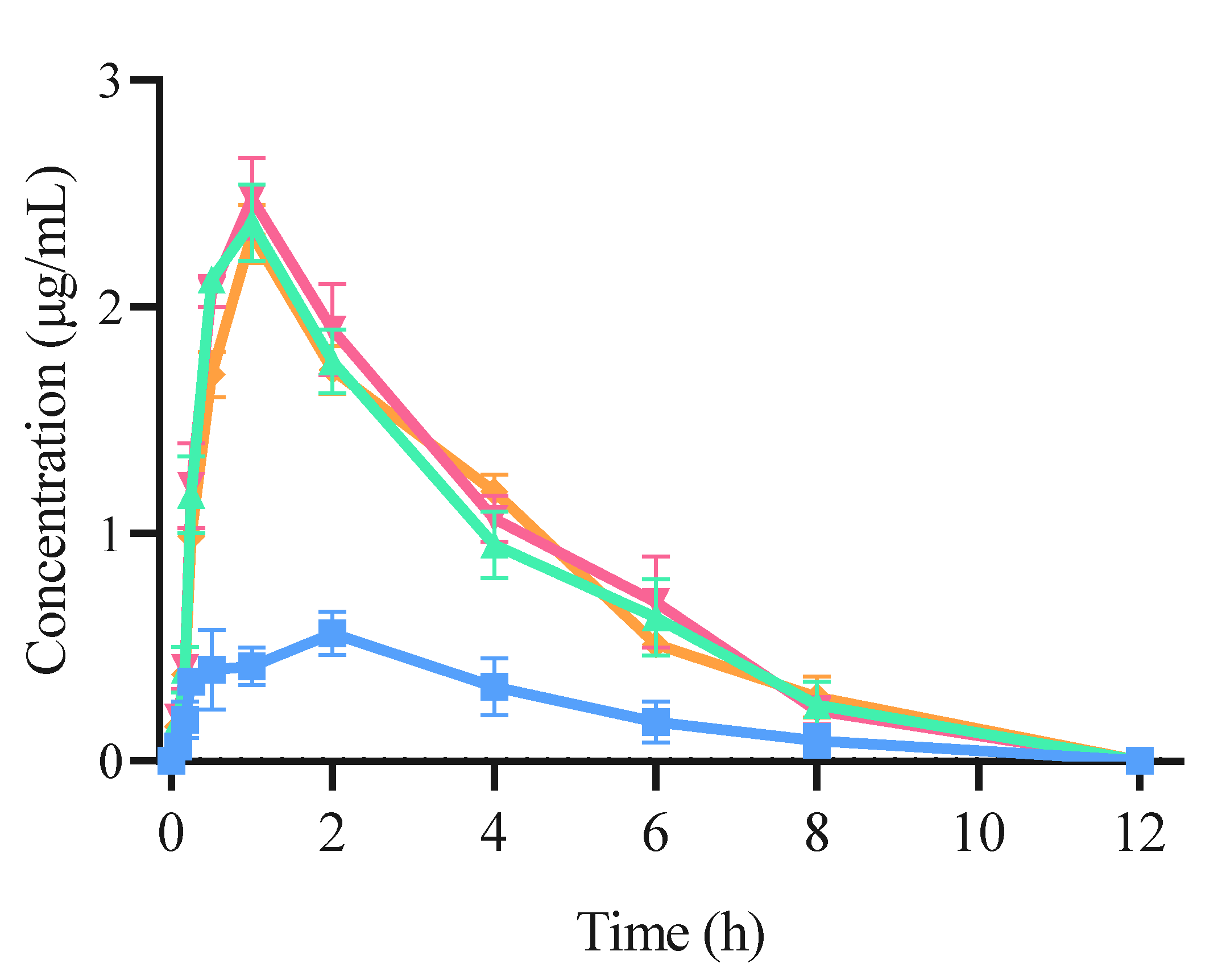

The plasma concentration–time curves following the intragastric administration of both free CRT and CRT/CD ICs are shown in Figure 9, and the main pharmacokinetic parameters are listed in . The pharmacokinetic curves of the three CRT/CD ICs were significantly better than those of free CRT, indicating that IC formation increased blood CRT concentration in rats. The peak concentration (Cmax) was 0.545 ± 0.023 μg/mL for free CRT, compared with 2.376 ± 0.118, 2.487 ± 0.126, and 2.355 ± 0.095 μg/mL for CRT/α-CD IC, CRT/HP-β-CD IC, and CRT/γ-CD IC, respectively. In addition, following oral administration (20 mg/kg), the time to reach the maximum concentration (Tmax) was 2 h for free CRT and 1 h for all three CRT/CD ICs.

Figure 9. Concentration–time curve of CRT pharmacokinetic profile using SD rats from (■) CRT, (▲) CRT/α-CD IC, (▼) CRT/HP-β-CD IC, and (◆) CRT/γ-CD IC (n = 6, mean ± S.D.).

Therefore, compared with free CRT, the three ICs significantly decreased the peak time of CRT in rats, and the relative bioavailability of the three ICs using α-CD, HP-β-CD, and γ-CD was increased by 4.35, 4.49, and 4.37 times, respectively. Therefore, CRT/CD IC significantly increased the peak concentration, absorption rate, and degree of CRT in vivo, consistent with the in vivo results for various IC formulations [33,56,57]. As calculated using Equation (2), the mean AUC0-∞ values of free CRT, CRT/α-CD IC, CRT/HP-β-CD IC, and CRT/γ-CD IC were 2.665 ± 0.196, 9.723 ± 0.222, 10.237 ± 0.343, and 9.869 ± 0.245 μg·h/mL (p < 0.01), respectively. This indicated that the CRT/CD ICs could significantly enhance the degree and rate of intestinal absorption of CRT. The bioavailability of free CRT was relatively low, possibly due to its poor solubility in water. The dissolution and absorption in the intestine were both low, lowering the drug contents in vivo. In contrast, the IC formation could improve the solubility of CRT, increase the amount of CRT dissolved in the intestine, and increase the amount of CRT entering the blood from the intestine. These results demonstrated that the oral relative bioavailability of CRT was increased by 3.68, 3.94, and 3.77 times when administrated as IC using α-CD, HP-β-CD, and γ-CD, respectively. CRT/HP-β-CD IC showed a slightly higher relative bioavailability than those of CRT/α-CD and CRT/γ-CD ICs, roughly analogous to the results of the solubility test. In a previous study, the highest plasma concentration of CRT was 1249.3 ± 788.1 ng/mL at approximately 2 h after oral administration in mice, even for a dose of 117.2 mg/mL [58]. Moreover, CRT or saffron tea administered orally to humans showed a Tmax concentration at approximately 4.6 h, and the concentrations of CRT in the blood ranged from 100.9 to 279.7 ng/mL based on the dose [59,60]. CRT/CD ICs could significantly reduce CRT dose to achieve a higher plasma concentration and shorten Tmax than those obtained in previous studies after oral administration.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we successfully prepared CRT/CD ICs using two natural CDs (α-, and γ-CD) and a modified CD (HP-β-CD) with lower toxicity than β-CD using the sonication method. Notably, we observed enhanced solubility, stability, and bioavailability of CRT. The formation of all three ICs was confirmed using FTIR, PXRD, SEM, and 1H NMR. Solubility and dissolution tests indicated that the three CRT/CD ICs significantly improved the water solubility of CRT. Further, IC formation can improve the stability of CRT during storage under heat, light, and moisture conditions. The inclusion ratios determined using phase solubility diagrams and the continuous variation method were 1:1 for CRT/α-CD IC and 1:2 for both CRT/HP-β-CD and CRT/γ-CD ICs. These three ICs of the CRT showed significantly lower peak times than those of pure CRT in rats, and the relative bioavailability of the three ICs using α-CD, HP-β-CD, and γ-CD was increased by 3.68, 3.94, and 3.77 times, respectively. These findings indicated that ICs can improve the relative bioavailability of CRT substantially in rats. NMR analysis, phase solubility study, and solubility tests revealed a superior inclusion efficiency of HP-β-CD with a higher Kc value, solubility, and relative bioavailability than the other two. However, α-CD and γ-CD showed certain advantages in terms of security and environmental friendliness. These three CDs were effective in carrying CRT, although further evaluation is warranted in terms of pharmacodynamics and toxicology. The preparation of CRT/CD ICs improved the oral relative bioavailability of CRT, offering a new approach for the development of cost-effective solid formulations or healthy foods based on CRT.

References

- Cardone, L.; Castronuovo, D.; Perniola, M.; Cicco, N.; Candido, V. Saffron (Crocus sativus L.), the king of spices: An overview. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 272, 109560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Deng, H.; Du, B.; Wu, P.; Duan, L.; Zhu, R.; Ning, Z.; Feng, J.; Xiao, H. Saffron Petal, an Edible Byproduct of Saffron, Alleviates Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis by Inhibiting Macrophage Activation and Regulating Gut Microbiota. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2023, 71, 10616–10628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kothari, D.; Thakur, R.; Kumar, R. Saffron (Crocus sativus L.): Gold of the spices—A comprehensive review. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2021, 62, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, B.M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Saffron: A promising natural medicine in the treatment of metabolic syndrome. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2017, 97, 1679–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefi, M.; Shafaghi, K. Saffron in Persian traditional medicine. In Saffron; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2020; pp. 393–404. [Google Scholar]

- Musazadeh, V.; Zarezadeh, M.; Faghfouri, A.H.; Keramati, M.; Ghoreishi, Z.; Farnam, A. Saffron, as an adjunct therapy, contributes to relieve depression symptoms: An umbrella meta-analysis. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 175, 105963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koşar, M.; Başer, K.H.C. Beneficial effects of saffron (Crocus sativus L.) in ocular diseases. In Saffron; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Imenshahidi, M.; Hosseinzadeh, H.; Javadpour, Y. Hypotensive effect of aqueous saffron extract (Crocus sativus L.) and its constituents, safranal and crocin, in normotensive and hypertensive rats. Phytother. Res. 2010, 24, 990–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finley, J.W.; Gao, S. A perspective on Crocus sativus L.(Saffron) constituent crocin: A potent water-soluble antioxidant and potential therapy for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2017, 65, 1005–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.-N.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Y.-H.; Liu, T.-L.; Zhang, C. Crocins: A comprehensive review of structural characteristics, pharmacokinetics and therapeutic effects. Fitoterapia 2021, 153, 104969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, Y.; Mishra, V. Multifaceted roles of crocin, phytoconstituent of Crocus sativus Linn. In cancer treatment: An expanding horizon. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 160, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.-F. Research progress on pharmacokinetics and dosage forms of crocin and crocetin. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs. 2019, 50, 234–242. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, A.; Razavi, B.M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Pharmacokinetic properties of saffron and its active components. Eur. J. Drug. Metar. Pharmacokinet. 2018, 43, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeinali, M.; Zirak, M.R.; Rezaee, S.A.; Karimi, G.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Immunoregulatory and anti-inflammatory properties of Crocus sativus (Saffron) and its main active constituents: A review. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2019, 22, 334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.-L.; Li, M.-X.; Li, X.-L.; Wang, P.; Wang, W.-G.; Du, W.-Z.; Yang, Z.-Q.; Chen, S.-F.; Wu, D.; Tian, X.-Y. Crocetin: A systematic review. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 12, 745683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Song, X.; Chang, X.; Zu, E.; Ma, X.; Sukegawa, M.; Liu, D.; Wang, D.O. Crocetin Alleviates Ovariectomy-Induced Metabolic Dysfunction through Regulating Estrogen Receptor β. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2021, 69, 14824–14839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batool, Z.; Chen, J.-H.; Gao, Y.; Lu, L.W.; Xu, H.; Liu, B.; Wang, M.; Chen, F. Natural Carotenoids as Neuroprotective Agents for Alzheimer’s Disease: An Evidence-Based Comprehensive Review. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2022, 70, 15631–15646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- José Bagur, M.; Alonso Salinas, G.L.; Jiménez-Monreal, A.M.; Chaouqi, S.; Llorens, S.; Martínez-Tomé, M.; Alonso, G.L. Saffron: An old medicinal plant and a potential novel functional food. Molecules 2017, 23, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltani, F.; Ramezani, M.; Amel Farzad, S.; Mokhtarzadeh, A.; Hashemi, M. Comparison study of the effect of alkyl-modified and unmodified PAMAM and PPI dendrimers on solubility and antitumor activity of crocetin. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2017, 45, 1356–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautenschläger, M.; Lechtenberg, M.; Sendker, J.; Hensel, A. Effective isolation protocol for secondary metabolites from saffron: Semi-preparative scale preparation of crocin-1 and trans-crocetin. Fitoterapia 2014, 92, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirhadi, E.; Nassirli, H.; Malaekeh-Nikouei, B. An updated review on therapeutic effects of nanoparticle-based formulations of saffron components (safranal, crocin, and crocetin). J. Pharm. Investig. 2020, 50, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, J.; Mohanty, C.; Sahoo, S.K. Protective efficacy of crocetin and its nanoformulation against cyclosporine A-mediated toxicity in human embryonic kidney cells. Life Sci. 2019, 216, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyshaburinezhad, N.; Kalalinia, F.; Hashemi, M. Encapsulation of crocetin into poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles overcomes drug resistance in human ovarian cisplatin-resistant carcinoma cell line (A2780-RCIS). Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019, 46, 6525–6532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Cui, M.-Y.; Zha, S.-H.; Tian, R.-R.; Zhao, Q.-S. β-cyclodextrin-based nanosponges for crocetin delivery: Physicochemical characterization, aqueous solubility, and bioactivity. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 384, 122235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.H.; Xie, Y.; Huang, X.; Kadota, K.; Yao, X.-S.; Yu, Y.; Chen, X.; Lu, A.; Yang, Z. Delivering crocetin across the blood-brain barrier by using γ-cyclodextrin to treat Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasheed, A. Cyclodextrins as drug carrier molecule: A review. Sci. Pharm. 2008, 76, 567–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulson, B.G.; Alsulami, Q.A.; Sharfalddin, A.; El Agammy, E.F.; Mouffouk, F.; Emwas, A.-H.; Jaremko, L.; Jaremko, M. Cyclodextrins: Structural, chemical, and physical properties, and applications. Polysaccharides 2021, 3, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Valle, E.M. Cyclodextrins and their uses: A review. Process Biochem. 2004, 39, 1033–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crini, G. A history of cyclodextrins. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 10940–10975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loftsson, T. Cyclodextrins in parenteral formulations. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 110, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-Y.; Li, C.-W.; Xu, Y.-J.; Yu, Q.; Liu, N.; Liu, D.-C. Optimization of the Preparation of Trans-crocetin from Crocin by Alkaline Hydrolysis via Response Surface Methodology. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2021, 42, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi, T.; Connors, K.A. Advances in Analytical Chemistry and Instrumentation; Interscience Publishers, Inc.: New York, USA, 1965; pp. 117–212. [Google Scholar]

- Soliman, K.A.; Ibrahim, H.K.; Ghorab, M.M. Effect of different polymers on avanafil–β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. Int. J. Pharmaceut. 2016, 512, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, N.; Ghosh, B.; Roy, D.; Bhaumik, B.; Roy, M.N. Exploring the inclusion complex of a drug (umbelliferone) with α-cyclodextrin optimized by molecular docking and increasing bioavailability with minimizing the doses in human body. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 30243–30251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.-N.; Jiang, X.-X.; Naeem, A.; Chen, F.-C.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.-X.; Li, Z.; Ming, L.-S. Fabrication and Characterization of β-Cyclodextrin/Mosla Chinensis Essential Oil Inclusion Complexes: Experimental Design and Molecular Modeling. Molecules 2022, 28, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wdowiak, K.; Rosiak, N.; Tykarska, E.; Żarowski, M.; Płazińska, A.; Płaziński, W.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Amorphous Inclusion Complexes: Molecular Interactions of Hesperidin and Hesperetin with HP-Β-CD and Their Biological Effects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wu, H.; Ao, X.; Hao, H.; Bi, J.; Hou, H.; Zhang, G. Characterization of the Inclusion Complexes of Isothiocyanates with γ-Cyclodextrin for Improvement of Antibacterial Activities against Staphylococcus aureus. Foods 2021, 11, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhang, W.; Xie, S.; Zhao, F.; Peng, X.; Qin, Z.; Zeng, D.; Zeng, Z. Enhancement of the oral bioavailability of isopropoxy benzene guanidine though complexation with hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin. Drug. Deliv. 2022, 29, 2824–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Gaetano, F.; Cristiano, M.C.; Paolino, D.; Celesti, C.; Iannazzo, D.; Pistarà, V.; Iraci, N.; Ventura, C.A. Bicalutamide Anticancer Activity Enhancement by Formulation of Soluble Inclusion Complexes with Cyclodextrins. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondal, M.; Basak, S.; Ali, S.; Roy, D.; Saha, S.; Ghosh, B.; Ghosh, N.N.; Lepcha, K.; Roy, K.; Roy, M.N. Exploring inclusion complex of an anti-cancer drug (6-MP) with β-cyclodextrin and its binding with CT-DNA for innovative applications in anti-bacterial activity and photostability optimized by computational study. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 30936–30951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Bie, C.; Ji, Q.; Ling, H.; Li, C.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Ye, F. Preparation and characterization of cyanazine–hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin inclusion complex. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 26109–26115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Yang, Q.; Wu, L.; Qi, R.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Tang, L.; Guo, D.-A.; Liu, B. Investigation of inclusion complex of patchouli alcohol with β-cyclodextrin. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, G.K.; Gallo, A.; Novicki, L.H.; Neto, H.R.; de Paula, E.; Marsaioli, A.J.; Cabeça, L.F. Inclusion Complex between Local Anesthetic/2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin in Stealth Liposome. Molecules 2022, 27, 4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Calsteren, M.-R.; Bissonnette, M.C.; Cormier, F.; Dufresne, C.; Ichi, T.; LeBlanc, J.Y.; Perreault, D.; Roewer, I. Spectroscopic characterization of crocetin derivatives from Crocus sativus and Gardenia jasminoides. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 1997, 45, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesari, A.; Recchimurzo, A.; Fabiano, A.; Balzano, F.; Rossi, N.; Migone, C.; Uccello-Barretta, G.; Zambito, Y.; Piras, A.M. Improvement of peptide affinity and stability by complexing to cyclodextrin-grafted ammonium chitosan. Polymers 2020, 12, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascenso, A.; Guedes, R.; Bernardino, R.; Diogo, H.; Carvalho, F.A.; Santos, N.C.; Silva, A.M.; Marques, H.C. Complexation and full characterization of the tretinoin and dimethyl-βeta-cyclodextrin complex. AAPS PharmSciTech 2011, 12, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivalli, K.M.R.; Mishra, B. Improved aqueous solubility and antihypercholesterolemic activity of ezetimibe on formulating with hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin and hydrophilic auxiliary substances. AAPS PharmSciTech 2016, 17, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Zheng, Z.-P.; Zhu, Q.; Guo, F.; Chen, J. Encapsulation mechanism of oxyresveratrol by β-cyclodextrin and hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin and computational analysis. Molecules 2017, 22, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Su, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, R.; Fu, X.; Li, Y.; Xue, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, R. Preparation and properties of cyclodextrin inclusion complexes of hyperoside. Molecules 2022, 27, 2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahad, A.; Bin Jardan, Y.A.; Hassan, M.Z.; Raish, M.; Ahmad, A.; Al-Mohizea, A.M.; Al-Jenoobi, F.I. Formulation and characterization of eprosartan mesylate and β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex prepared by microwave technology. Drug Deliv. 2022, 29, 1512–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Azevedo, M.d.B.M.; Tasic, L.; Fattori, J.; Rodrigues, F.H.; Cantos, F.C.; Ribeiro, L.P.; de Paula, V.; Ianzer, D.; Santos, R.A. New formulation of an old drug in hypertension treatment: The sustained release of captopril from cyclodextrin nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2011, 6, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, C.; Jin, Z.; Xu, X. Inclusion complex of astaxanthin with hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin: UV, FTIR, 1H NMR and molecular modeling studies. Carbohyd. Polym. 2012, 89, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, S.S.; Alshehri, S.; Mahdi, W.A.; Alotaibi, A.M.; Alhwaifi, M.H.; Hussain, A.; Altamimi, M.A.; Qamar, W. Formulation of multicomponent chrysin-hydroxy propyl β cyclodextrin-poloxamer inclusion complex using spray dry method: Physicochemical characterization to cell viability assessment. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, S.S.; El-Saleh, F.; Lysenko, K.; Paz, F.A.A. Inclusion compound of efavirenz and γ-cyclodextrin: Solid state studies and effect on solubility. Molecules 2021, 26, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paramera, E.I.; Konteles, S.J.; Karathanos, V.T. Stability and release properties of curcumin encapsulated in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, β-cyclodextrin and modified starch. Food. Chem. 2011, 125, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.B.; Attimarad, M.; Al-Dhubiab, B.E.; Wadhwa, J.; Harsha, S.; Ahmed, M. Enhanced oral bioavailability of acyclovir by inclusion complex using hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin. Drug Deliv. 2014, 21, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesharwani, P.; Johnston, T.P.; Sahebkar, A. Anticancer potential of curcumin-cyclodextrin complexes and their pharmacokinetic properties. Int. J. Pharmaceut. 2022, 631, 122474. [Google Scholar]

- Asai, A.; Nakano, T.; Takahashi, M.; Nagao, A. Orally administered crocetin and crocins are absorbed into blood plasma as crocetin and its glucuronide conjugates in mice. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2005, 53, 7302–7306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umigai, N.; Murakami, K.; Ulit, M.; Antonio, L.; Shirotori, M.; Morikawa, H.; Nakano, T. The pharmacokinetic profile of crocetin in healthy adult human volunteers after a single oral administration. Phytomedicine 2011, 18, 575–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chryssanthi, D.G.; Lamari, F.N.; Georgakopoulos, C.D.; Cordopatis, P. A new validated SPE-HPLC method for monitoring crocetin in human plasma—Application after saffron tea consumption. J. Pharmaceut. Biomed. 2011, 55, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]