1. Introduction

It is estimated that 400,000 people in the UK have type 1 diabetes (T1DM), and this figure is increasing by approximately 4% per year, ranking the UK with one of the highest rates of T1DM in the world [1]. Of this total, 29,000 are children and young people (CYP), representing the highest number of CYP aged 0–14 with T1DM in Europe [2]. Although the literature concerning the risk factors for developing T1DM is well established, the reason why T1DM is increasing is not fully understood, and this is likely to remain the case for the foreseeable future despite ongoing research targeting the prevention of T1DM. Therefore, it makes sense to concentrate efforts on the management of the condition, optimising the care that children, young people and their families (CYPF) receive and ensuring they are supported in the best way possible to improve diabetes outcomes and general health and wellbeing. This includes providing an individualised, integrated package of care delivered by a multidisciplinary paediatric diabetes team alongside self-management [3].

T1DM is one of the most common chronic, lifelong conditions in CYP, and self-management represents a constant challenge, as CYP need to adhere to a daily insulin regimen to maintain appropriate blood glucose levels [4]. People with T1DM spend over 10,000 h per year self-managing their condition, significantly more than the scant 3 h per year interacting with a healthcare professional (HCP) [5]. Given the responsibility for self-management that is placed on CYP with T1DM, it is important that they receive the appropriate diabetes skills and support to be empowered to manage their condition.

One component of the package of support available for CYP is that provided by diabetes technology, namely insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), including apps that can be downloaded onto a mobile device. In recent years, the number of CYP using technology has increased substantially, helping CYP to better control their diabetes while also reducing the burden of self-management [6,7,8]. Evidence-based standards for diabetes self-management and support advocate the use of technology, particularly engagement platforms such as apps, in what is a developing and expanding market [9]. Indeed, various systematic reviews have shown that apps can help to improve self-efficacy regarding the self-management of T1DM and the maintenance of target HbA1c levels [10,11].

The DigiBete app is a free self-management and educational app and video platform for CYPF and HCPs that was designed as an intervention to help CYPF manage T1DM. The app was designed by DigiBete (https://www.digibete.org, accessed on 13 December 2023) in collaboration with CYPF and HCP. It provides an ever-increasing range of clinically approved and age-appropriate resources to help with self-management, including access to over 200 T1DM films, for example, carbohydrate counting, sports and exercise. In addition, the app offers the ability to store insulin ratios/doses and pump settings and enables the user to receive communications directly to the app from their diabetes team [12]. The app is also available in different languages, including British Sign Language, Arabic, Bengali, Chinese, Polish, Somali, Tamil, and Urdu, and this list has been further extended. The DigiBete app has been introduced in 230 clinics nationally across the UK and is in partnership with the National Children and Young People’s Diabetes Network and the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust. It is used by CYP in an age range of 5–16 years and their parents/guardians.

The importance of thoroughly evaluating the implementation of healthcare interventions is widely recognised [13]. A key component of evaluations necessarily includes the perspectives of CYPF and key stakeholders, for example, HCPs [3,14,15]. This is part of a patient-centred approach outlined in the policy guidance provided by the Department of Health [16]. Therefore, this evaluation investigated the implementation of the DigiBete app from the perspective of these key stakeholders, including what worked well and why as well as what aspects of the app did not work as well and the reasons for this. A main driver of the evaluation was to ascertain what needed to be done to refine the app to help support CYPF with their T1DM and to assist HCPs to this end.

Therefore, the aim of this investigation was to evaluate the impact and implementation of the DigiBete app with a focus on assessing the utility of the DigiBete app regarding self-management education and improved outcomes for CYPF with T1DM and to explore its on-going efficacy as a resource for both HCPs and CYPF.

2. Materials and Methods

The evaluation was a mixed-method, multi-site service evaluation, and investigative data were collected at sites between 1 November 2020 and 29 February 2023. A partnership approach, where independent evaluators were assisted with some evaluation activities by partners (e.g., DigiBete and the delivery sites), formed the basis of the evaluation framework. This was to gain the views of key stakeholders in the design and delivery of interventions as advocated by Eldredge et al. [14] and the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [13] and, in this case, specifically the experiences of HCPs and CYPF who were using the DigiBete app. The DigiBete app can be downloaded at the following link: https://apps.apple.com/gb/app/digibete/id1488447232, accessed on 13 December 2023). Further information on the app can be found here: https://www.digibete.org/digibete-app/, accessed on 12 December 2023.

The aim of this investigation was to evaluate the impact and implementation of the DigiBete app. To meet the aim, the objectives for the service-level evaluation were as follows:

- To investigate children’s, young people’s, families’, and healthcare professionals’ qualitative experiences of using the app during the first year of care following diagnosis of T1DM in children and young people;

- To identify which parts of the DigiBete app worked well and why as well which parts of the DigiBete app did not work as well and why;

- To collect quantitative data on the use of the app of CYP with T1DM within one year of diagnosis.

2.1. Instrumentation and Sampling

Five NHS hospitals across England participated in the evaluation from which participants were recruited, ensuring geographical diversity. At four sites, both qualitative and quantitative data were collected regarding the objectives above. At the fifth site only, qualitative data were available and were collected at the time of the evaluation.

2.2. Ethics and Recruitment

The required NHS Research and Development approvals for the evaluation were obtained through the relevant Research and Development (R&D) Department at each of the five NHS sites prior to recruitment. Following submission of an application/information, the R&D Departments assessed the investigation as either an audit or a service-level evaluation. Approval numbers were not provided. At their request, evidence of the R&D approvals were shared with the editorial team at Children, and this evidence is stored in the non-published materials. CYPF were invited to participate in the evaluation by letter, which was distributed via a gatekeeper through the email function of the DigiBete app. All potential participants were provided with an information sheet and consent form, as per normal practice. Prior to formally engaging in the evaluation, CYPF were required to provide informed consent and were made aware that they could withdraw at any time without giving a reason. They were also informed how they could withdraw from the evaluation.

For HCPs who were members of the diabetes teams, information about the evaluation and what participation involved was promoted to HCPs internally as part of the team’s multi-disciplinary team meetings. Following this, HCPs were invited to contact members of the evaluation team directly to express an interest in taking part in a semi-structured interview. Participation in the evaluation was voluntary. These HCPs were then issued an information sheet, and prior to taking part in the interview, HCPs provided informed consent and were informed how they could withdraw from the evaluation without giving a reason.

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Data

Findings from CYPF, using the data sources outlined above, aimed to determine the impact of the DigiBete platform and evaluate the impact of remote support to aid in better diabetes self-management. Results were generated for data that were collected up to February 2023.

3.2. The DigiBete Platform

The data were captured via the DigiBete app for the four participating NHS Trust sites and are summarised in below. Users of the app were CYP in the age range of 5–16 years as well as their parents and/or their guardians.

Initial findings show that there are N = 1165 CYPF DigiBete app users across the four sites, indicating a wide reach across the service. Data capture for demographic information was variable. However, of the participants providing information, 55.7% (n = 512/919) of app users were female, showing a relatively even split by gender. On average, the app users had been diagnosed for between 3.1 years and 4.2 years, which indicated that the content is valuable in maintaining diabetes control for CYPFs beyond the initial diagnosis period and helpful in sustaining healthy practices. In total, 4855 videos were viewed across the participating areas, with an average of 1213 videos per site (range of 776–1679) and 4.4 videos per app user, which indicated that users were returning to the site to view and digest content.

Regarding the most popular videos, “My Sick Day Rules” (which outlines the actions that CYPF should take when they are feeling unwell because of their T1DM) was the most popular, followed by “How to give a glucagon injection”. There were a wide range of other videos viewed that covered areas from exercise, nutrition, and general diabetes knowledge. This engagement with the videos on the app highlights the cross-cutting appeal of DigiBete, and in turn, this is likely to have reduced the demand created by clinic requests, therefore saving HCPs time and resources. Moreover, these videos are likely to be an integral part of the on-going package of care and continued programmes of education while providing up-to-date information that NICE recommends should be offered to CYPF with T1DM. DigiBete continues to promote access to learning and education to help CYPF manage T1DM.

Not only did CYPFs engage with videos on the app, but they also utilized quizzes and achieved awards, therefore broadening their understanding and consolidating their learning. For example, 902 quizzes were completed across the participating areas, with an average of 226 per site (range of 136–293), just short of one quiz per app user. The average quiz score across the participating sites ranged from 61% to 69%. This learning can aid in developing skills that are essential to living with T1DM and navigating challenges as patients become older.

3.3. Survey Results: Health Care Professionals

The following analysis is based on a sample of n = 178 HCPs from multiple sites across the country who provided responses between December 2020 and December 2022.

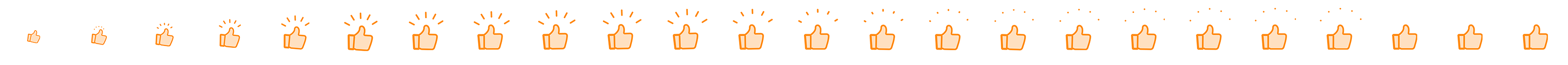

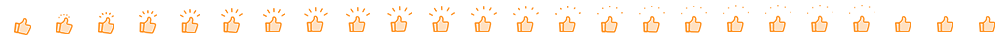

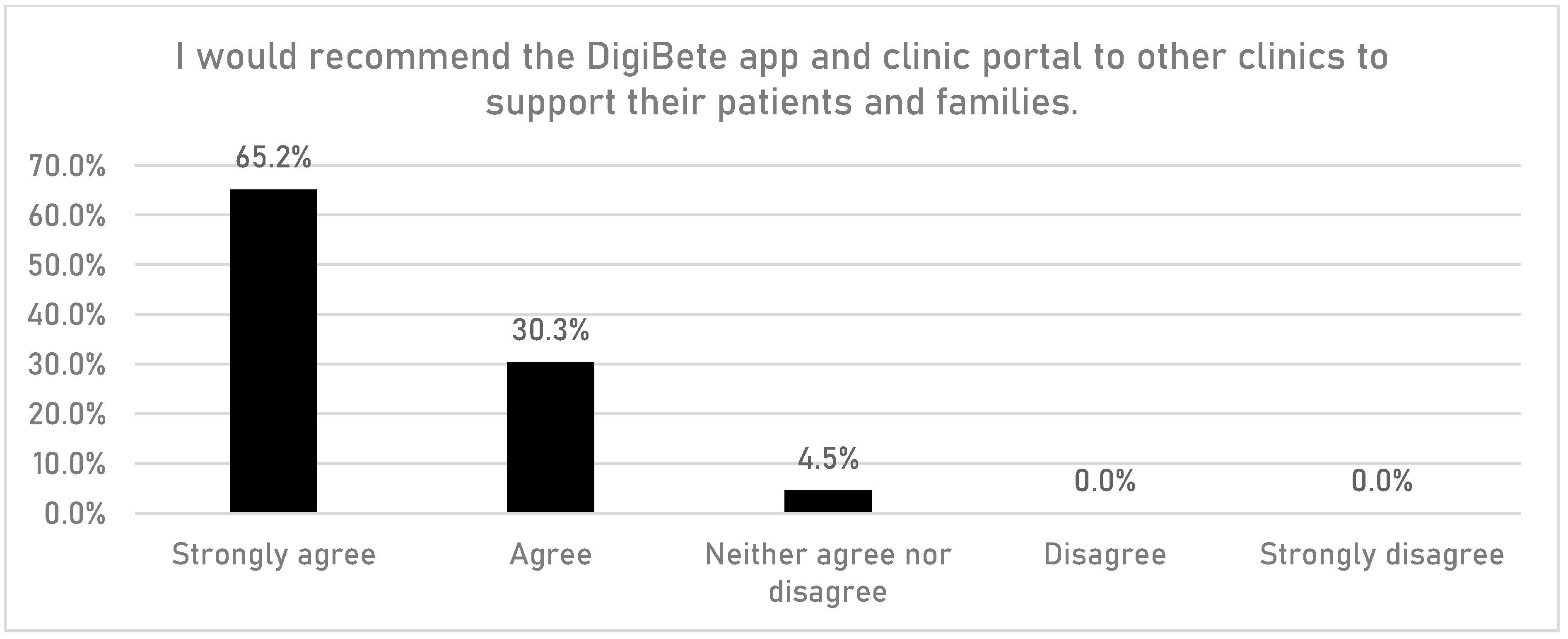

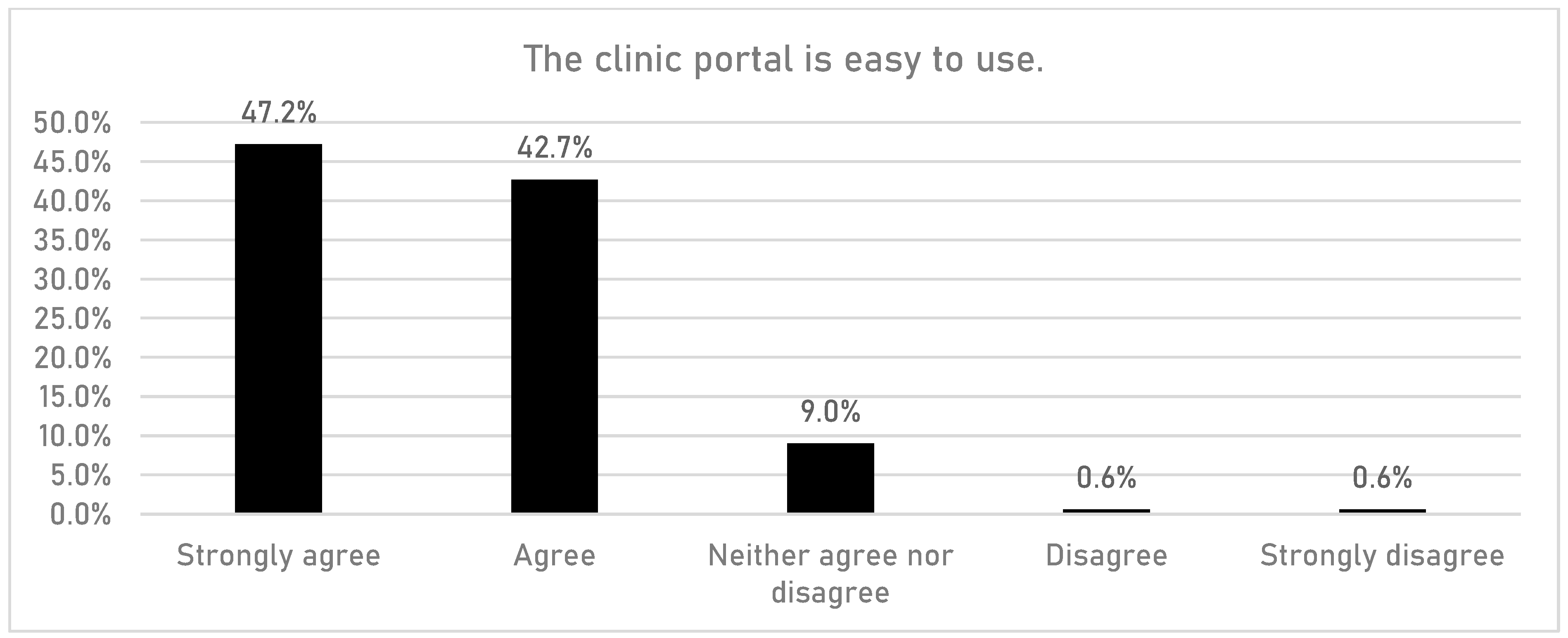

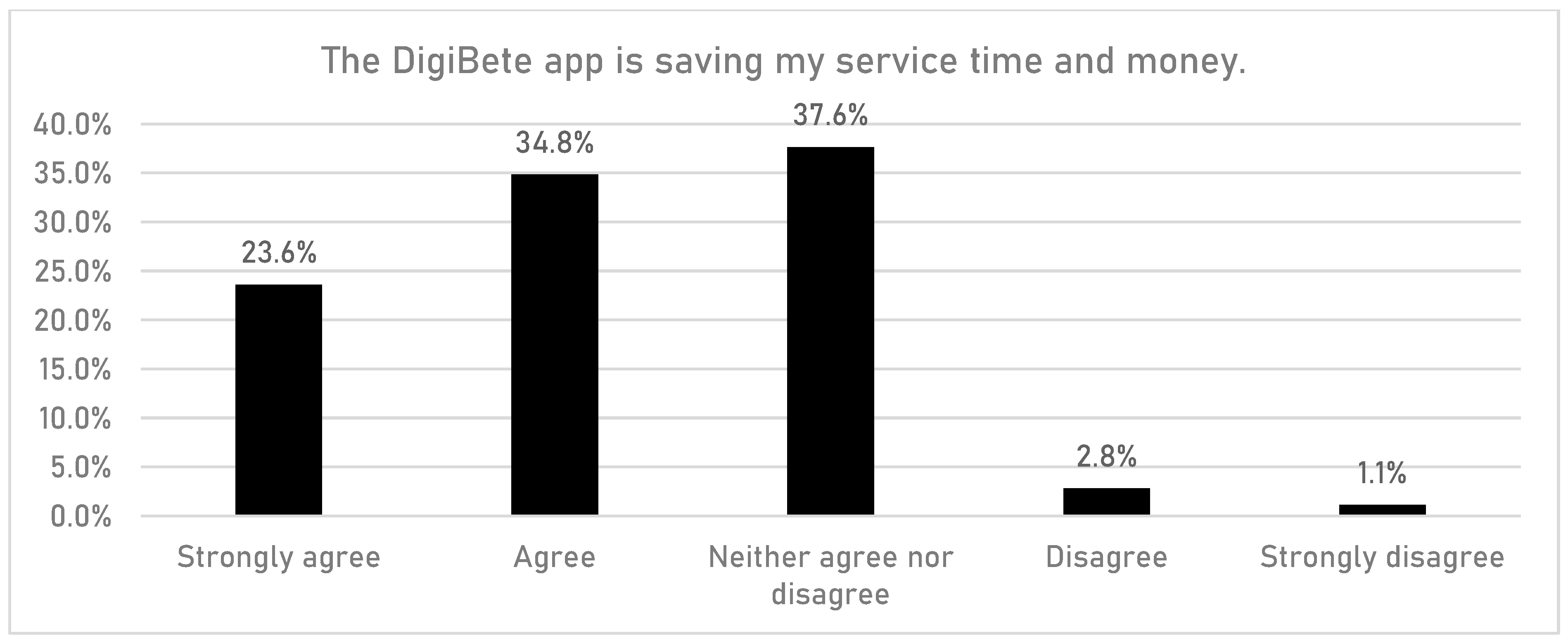

HCPs were asked if having access to the DigiBete app helped patients to manage their T1DM (Figure 1). In total, 83.7% (n = 149/178) of respondents reported that they agreed or strongly agreed with that statement. Furthermore, HCPs were asked if their clinic sent out information and news to support their patients and families via the clinic portal in the app (Figure 2). Overall, more than half of HCPs surveyed (55.6%, n = 99/178) reported that they frequently or very frequently did. The next question asked whether HCPs would recommend DigiBete to other clinics (Figure 3), and 95.5% (n = 170/178) of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they would recommend DigiBete. Moreover, HCPs were asked if the clinic portal on the DigiBete app was easy to use (Figure 4), and 89.9% (n = 160/178) of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that it was. Finally, 58.4% (n = 104/178) of HCPs agreed or strongly agreed that the DigiBete app was saving their service time and money (Figure 5). In addition, HCPs were asked about the functionality of the app and which parts were most useful in supporting patients. Access to education, quizzes, videos, and resources (30.4%) was deemed to be the most useful, followed by the app creating a place for patients to access their own clinic’s information (20.8%) and having the ability to create groups of patients and send customisable clinic support and updates (20.5%).

Figure 1. Helping patients manage their diabetes (according to HCPs).

Figure 2. Supporting families via the DigiBete app (according to HCPs).

Figure 3. Recommending the DigiBete app (according to HCPs).

Figure 4. The clinic portal (according to HCPs).

Figure 5. Saving time and money (according to HCPs).

3.4. Survey Results: Children and Young People and Their Families

The following analysis is based on a sample of n = 1165 CYPFs from multiple sites across the country who provided responses between October 2020 and October 2022.

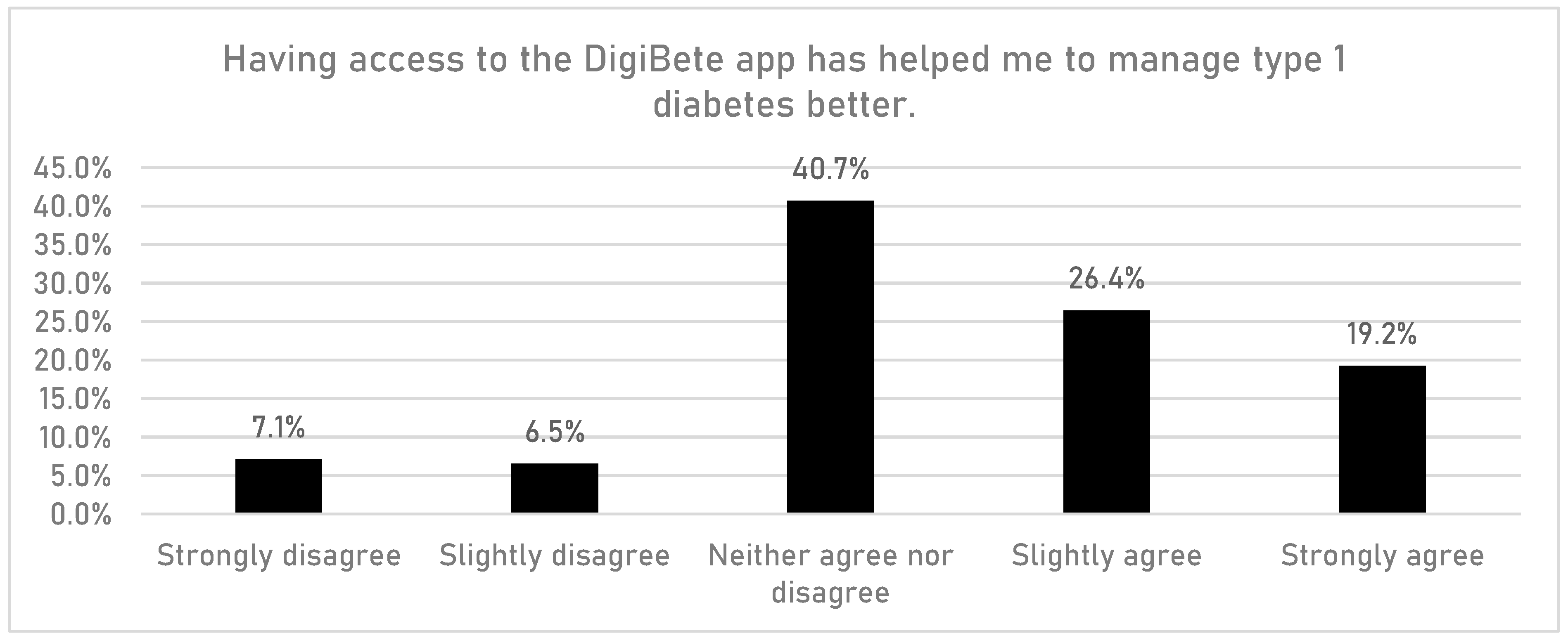

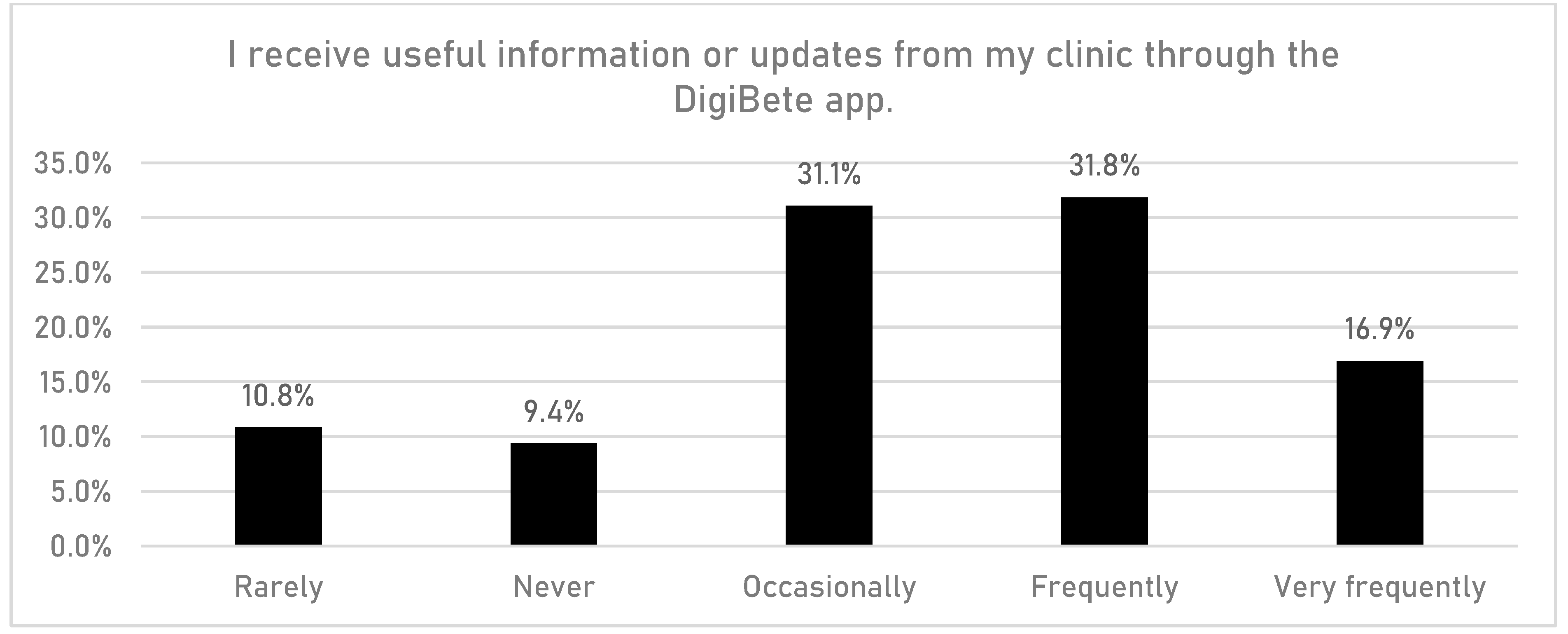

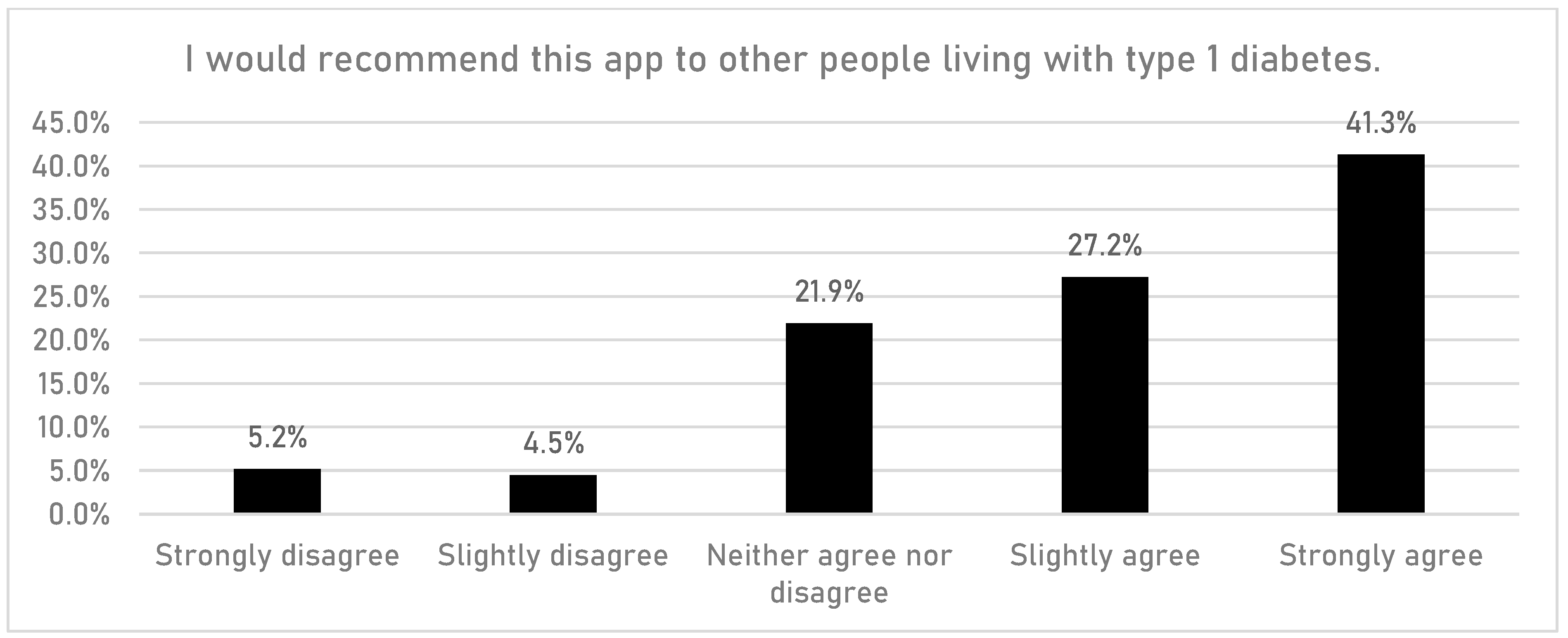

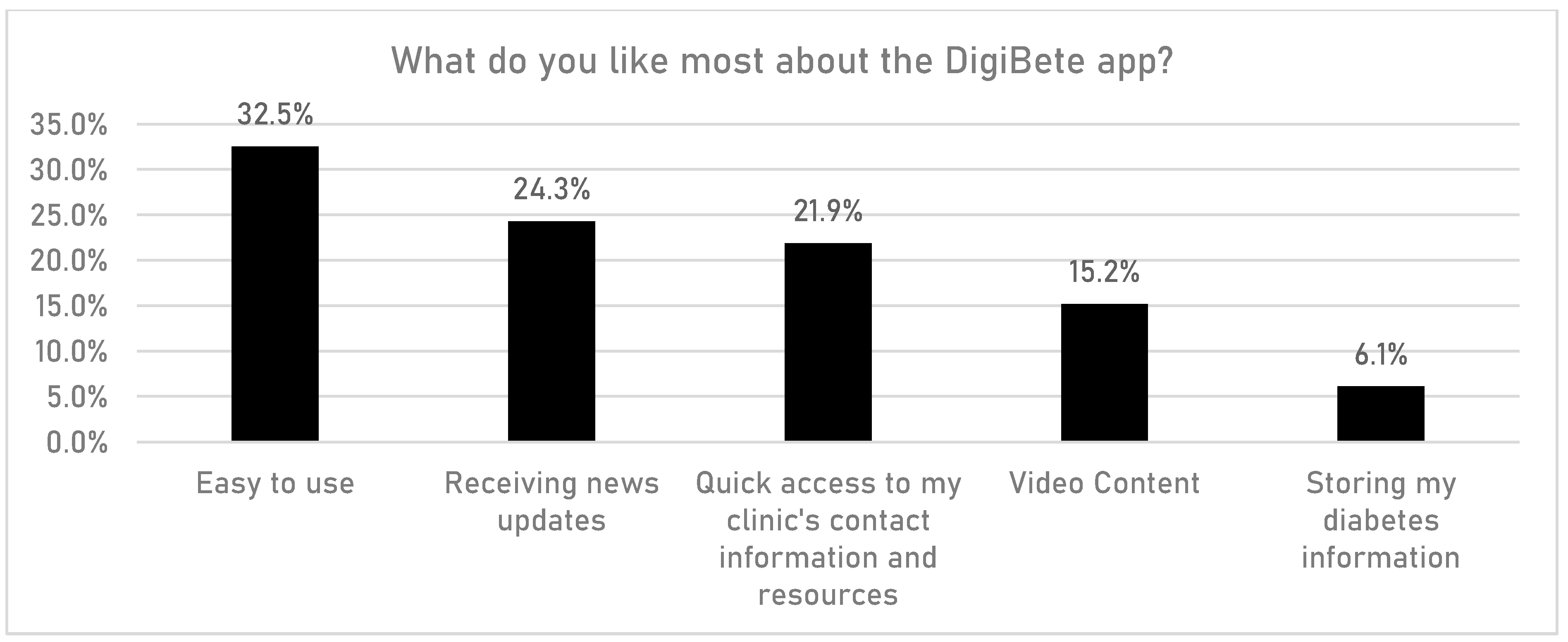

CYPFs were asked if having access to the DigiBete app helped them to manage their T1DM better (Figure 6). In total, 45.7% (n = 532/1165) of respondents reported that they slightly agreed or strongly agreed with that statement. Furthermore, CYPFs were asked if they received useful information or updates from their clinic through the app (Figure 7). Overall, around half of CYPFs surveyed (48.8%, n = 568/1165) reported that they frequently or very frequently did. The next question asked whether CYPFs would recommend DigiBete to other people living with T1DM (Figure 8), and 68.5% (n = 798/1165) of respondents slightly agreed or strongly agreed that they would recommend DigiBete. In addition, CYPFs were asked about what they liked most about the app (Figure 9). The most popular response was that it was easy to use (32.5%), followed by the ability to receive news updates (24.4%) and have quick access to their clinic’s contact information and resources (21.9%). Moreover, CYPFs were asked what they used the app for (Figure 10). Receiving updates from their clinic was the most popular response (32.7%), along with accessing resources (31.5%).

Figure 6. Helping manage diabetes (according to CYPFs).

Figure 7. Being supported via the DigiBete app (according to CYPFs).

Figure 8. Recommending the DigiBete app (according to CYPFs).

Figure 9. DigiBete app features (according to CYPFs).

3.5. Qualitative Data

In total, n = 63 participants, namely n = 38 CYPF and n = 25 HCPs, were interviewed. The CYP were aged between 5 and 16 years. For HCPs (n = 25), this comprised doctors (n = 3), nurses (n = 14), and other healthcare professionals (n = 8). The results are presented for CYPF and HCPs and grouped according to nine key themes that emerged from the interviews. Selected quotations from the interviews are detailed in this section.

3.6. Interviews with CYPF

3.7. Interviews with HCPs

4. Discussion

Diabetes technology for use by young people and their families can optimise T1DM management and outcomes from an early age [22]. Disease management requires interdisciplinary care coordination between CYPF and HCPs as well as others involved in the care of CYP with T1DM [22]. The importance of thoroughly evaluating the implementation of healthcare interventions is widely recognised [13]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first service-level evaluation of an app for the self-management of T1DM to investigate the perspectives of CYPF and HCPs in the use of DigiBete, a digital app for self-management of T1DM. The key findings indicate that CYPF and HCPs found the app an essential tool in the management of T1DM. CYPF and HCPs felt the app provided a valuable educational resource in a central place, and it was invaluable in an emergency or unknown situation. Furthermore, the app was a trusted and bona-fide source of information that could be accessed at any time, and it helped CYPF take back some of the control in managing their diabetes. In a climate of scarce health resources, HCPs felt the app had been a contributory factor in saving the NHS time and money. For example, almost two-thirds of HCPs agreed or strongly agreed that the DigiBete app was saving their service time and money. In addition, CYPF and HCPs identified areas for improvements, which shared with the developers so they can refine the app.

The NHS has been profoundly affected by the availability of mobile devices and apps in recent years, especially since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. More than 90,000 new apps were added to app stores in 2020 [1]. The rise in popularity of apps has enabled patients to engage with the health system through virtual visits, track their general health metrics, and, importantly, monitor and manage their health condition or symptoms remotely [1]. Resource issues and capacity have been some of the major drivers of this shift as well as the need for better communication and fast access to information at the point of care. The DigiBete app provides a “one-stop-shop” intervention to help CYPF and HCPs.

4.1. How the DigiBete App Was Used by CYPF and HCPs

The NDPA Spotlight Report highlights that, in general, CYPF are benefitting from using diabetes-related technologies to manage their condition depending on the paediatric diabetes service they attend [6]. Indeed, in this study, CYPF reported that the app helped them change their behaviour to manage their T1DM. Furthermore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, CYPF and HCPs reported using the app to access information on lifestyle and to check “My Sick Day Rules” at a time when there were restrictions on what people were permitted to do and where people could go. This extended the reach of the diabetes services. Alaslawi reported that the potential for technology to become an integral part of T1DM routine care has been accelerated due to the pandemic, a situation which resulted in reduced or non-existent face-to-face CYPF and HCPs interactions. Indeed, CYPF reported that having the app during the pandemic was very reassuring, especially for parents who were worried about their child having a diabetes episode and needing to be able to access trusted information about what to do in unknown circumstances [23].

HCPs reported that the app was helpful in their practice when working with them in clinics and at home, particularly for newly diagnosed CYP. Some HCPs found that they needed to be both flexible and creative when encouraging CYPF to use the app. With some CYPF, HCPs were constantly having to promote the app and had to consider the readiness and preparedness of CYPF to engage in the app. HCPs sometimes needed to adopt negotiating strategies for encouraging CYPF who might be more resistant to using the app. HCPs referred to “picking and choosing their battles” with more reluctant, resistant, or rebellious young people in terms of when would be the right time, if at all, to encourage their use of the app. Even if CYP were not prepared to engage at that point, the app provided the facility for them to re-engage with the content when they were ready to do so at a later stage.

4.2. The Importance of the DigiBete App

For the CYPF, the app was helpful in navigating the sheer volume of information that is available on T1DM, especially when first diagnosed, which can be an overwhelming and stressful time for CYPF. The app provided CYPF with an opportunity to go back and retrieve information on managing their T1DM effectively and at a time when they were in the necessary “headspace” and could more readily process the information they required. As the information was available online, it was centrally available to all users and seen as a determinant to better self-care, which was appreciated by CYPF. Furthermore, they could access answers to their questions immediately rather than having to call HCPs, and they used the app frequently to refresh their knowledge on relevant topics, for example, how to give an injection. CYPF reported that the app helped them take back some control and autonomy when managing their T1DM, especially when recently diagnosed or when they were away from their normal routine, for example, on a family holiday or school trip. CYPF also said the app was helpful for people who were looking after their child, specifically when a child was on a school activity during which a teacher needed more information or when a grandparent was looking after their grandchild. Families of younger children used the age-specific videos, and HCPs encouraged parents to watch the videos with their children to help facilitate learning and development. For teenagers, research has identified that adolescence is a time when young people seek to achieve increasing independence and to separate emotionally from their parents, prioritising relationships with their peers [22]. The app was seen as a tool to help young people make the transition from being dependent on their parents to achieving independence and managing their own T1DM.

Our findings indicate that CYPF found the app reassuring in this respect, knowing that CYP could access key information on the app whenever they needed it, for example, managing T1DM after consuming alcohol. An additional advantage of the app was that it gave CYP autonomy and meant they did not have to speak with an adult or one of their parents if they chose not to. Moreover, HCPs informed us that some CYP were reluctant to engage with them in the clinic, and therefore, the app provided an opportunity for CYP to access the information they needed when they were ready. CYPF found the videos on recipes helpful for young people when they started university and needed to cook for themselves. However, one of the most important ways that CYPF used the app was for the “My Sick Day Rules” to help them manage an unknown situation or when they were feeling poorly due to their diabetes. HCPs felt that having information in an app that was easily accessible meant that some CYPF were more likely to use the app as a first port of call for information to self-manage their T1DM rather than ringing the clinic straightaway. HCPs reported that there were CYPF who, in an unknown situation or T1DM crisis, had used the “My Sick Day Rules” in the app initially instead of contacting their diabetes nurse or clinic, This not only helped CYPF manage their situation, but it also helped save scarce NHS resources such as HCPs’ time. However, CYPF knew to contact their diabetes team if they had additional concerns and/or the problem could not be addressed by using the app. It should also be stated that the “My Sick Day Rules” feature in the app aims to supplement NHS guidance, which recommends CYPF contact their diabetes team if they have a “hypo”. Furthermore, HCPs also reported that the app was a trusted and bona-fide source of information that CYPF could consult for correct advice. This contrasted with web-based resources, which could not be relied upon to be accurate, potentially leading to the worsening condition of CYP and more urgent medical intervention.

HCPs felt the app was an important tool to be used alongside regular clinic visits, during which they could direct CYPF to the many different features of the app, for example, videos, “My Sick Day Rules”, and key HCP contacts. However, some HCPs reported that they were required to constantly nudge CYPF to use the app. This was important in helping CYPF to appreciate the benefits of the app, which became increasingly apparent the more the CYPF used it. Furthermore, in the context of limited healthcare resources, the app meant HCPs could send out group notifications when previously they would have had to “stuff and label” envelopes to send to CYPF. Interviews with CYPF and HCP indicated that learning had taken place, and this was reflected in examples of CYPF who amended their lifestyles as well as the practices that enhanced their preparedness for managing their or their child’s diabetes. It would be valuable to add to the learning identified in this evaluation in future research and to further investigate both the depth of learning that took place and how this was best facilitated.

4.3. How the DigiBete App Could Be Improved

Overall, CYPF and HPCs were very positive about the app, but as with any intervention, our service-level evaluation identified areas for improvement. This reflects the benefits of undertaking an evaluation of an intervention from the perspective of key stakeholders [13,14,15] and a genuine aspiration to improve the app and better serve the needs of CYPF.

Lupton [24] reported that CYP appreciate the availability of information online and the opportunities to learn more about their bodies and how to improve their health and physical fitness. They enjoy being able to connect with peers and they find emotional support and relief from distress by using social media platforms, for example, YouTube and online forums. Research has indicated that CYPF are active users of digital health technologies, but it is notable that they still rely on older technologies such as websites and search engines to find information [24]. Therefore, it is important in an evaluation of the DigiBete app to examine how CYPF use various platforms for accessing information on different content. CYPF identified an area for improvement in the app, which was the ability to communicate with other CYP who had T1DM. They stated that such a feature would have been particularly advantageous during the pandemic when lockdown restrictions were in place. However, this poses additional considerations regarding monitoring and safeguarding in the use of the app and the associated resources involved in these activities.

As well as increased interaction with CYP with T1DM through the app, CYPF reported that it would be beneficial if the app could facilitate real-time engagement with HCPs. This was seen as especially important during the pandemic when some CYPF experienced increased isolation [25]. Clearly, interaction with HCPs through the app poses an additional resource challenge for services that are already working to full capacity [26].

Furthermore, CYPF suggested they would benefit from a print function on the app to enable them to print the newsletters and important information; a link to the quizzes in order to see if CYP were learning from the content on the app; the ability for the app and a diabetes pump to “speak” to one another to avoid input error; and the ability to share their T1DM care plan with other people, particularly staff in schools. Also, CYPF wanted to see links to mental health support and content focused on the management of T1DM in relation to key life events, for example, starting school, going to university, and starting a new job.

HCPs suggested that the usefulness of the app could be increased by considering the order in which content appeared on the app, particularly for those who were newly diagnosed; syncing clinic appointments through the app; and incorporating more images to accommodate the needs of those individuals for whom English was not their first language. Helping to make the app an integral part of diabetes services has been identified as important for ensuring clinical effectiveness. However, while some apps support HCP engagement/consultation, many others have little or no involvement with the healthcare team [8,10], Our results demonstrate that this was not the case for the HCPs and the DigiBete app. The HCPs that we interviewed did engage with the app; indeed, HCPs or DigiBete champions were often the main drivers and promoters of the app, especially with newly diagnosed CYPF. For example, HCPs used the app on a regular basis to communicate with CYPF and post notifications for their attention. In this respect, the DigiBete app differs from most other apps, which is one of its unique selling points, as emphasised by both the CYPF and HCPs.

Evaluating public health interventions is important to help improve their delivery [27]. Having highlighted the different improvements that CYPF would like to see, our findings have identified that CYPF have different needs and expectations of the app, which can pose a challenge in catering to everyone. On-going communication from HCPs to CYPF, in terms of what to expect from the app, becomes even more important when promoting its use [28]. Therefore, in facilitating engagement, working with HCPs to make apps useful for the routine care of CYP is a good investment. The involvement of end-users in research can enhance its quality, relevance, credibility, and legitimacy [27,29]. Brew-Sam advocated an integrative approach involving CYP, parents, and health care providers to develop future technology [22]. Feedback from these groups is regarded as extremely valuable when improving health systems to meet the needs of CYPF. However, this can result in rising expectations of CYPF regarding their T1DM care. Our findings and the literature demonstrate how important it is that CYPFs’ expectations of the app do not translate into additional demands on HCPs, many of whom already report increasing workloads [26].

4.4. Inequalities and Use of the App

When delivering technological interventions, an important aspect to consider is that of inequalities in technology. This includes the ability of CYPF to afford smartphones and the functionality to access apps and a home Wi-Fi connection. These issues were not widely apparent in our evaluation, and similarly, the absence of ability to access IT hardware and software were not evident in the CYPF we interviewed. However, HCPs reported that they experienced difficulties when accessing the app on ageing departmental phones and/or slow organisational Wi-Fi connections. These are important considerations when developing technology-based interventions [30,31]. Furthermore, we asked HCPs if CYPF experienced difficulties with buying a smartphone and purchasing data for accessing the app. In most cases, this was not an issue. HCPs reported that having a smartphone was regarded as a basic requirement if not a necessity. Some NHS Trusts had levelling-up initiatives for tackling digital poverty, which involved distributing IT hardware such as laptops to CYPF most in need or recycling old smartphones. CYPF who were refugees had, in some cases, been given a smartphone bought by their host families. At one site, HCPs reported that families changed their smartphone contract frequently to obtain the most competitive phone contract or deal, and this meant that, on occasions, their telephone number changed. Another difficulty occurred when families changed phone contracts, and the transfer of apps from the old to the new phone did not always happen. This meant CYPF had to download the DigiBete app to their new phone again and re-input the clinic code to access the app, which sometimes they did not do. This led to problems and an inability to carry on using the app.

An issue that emerged from our findings with the CYPF and HCPs was that, regardless of the family, while some preferred the app, the app did not replace face-to-face contact with HCPs. Rather, it was part of a “toolbox” of services offered by diabetes teams to help all CYPF manage T1DM. The literature indicates that CYPF frequently turn to trusted adults to help them make sense of online information and to provide alternative sources of support [24]. Therefore, face-to-face interactions, either virtual or digital, with HCPs remain important for all families when supporting them with their management of T1DM.

4.5. Limitations and Strengths

Learning from the process of conducting evaluations is important [27]. Limitations might indicate that the external validity of the results of this evaluation may be limited due to volunteer bias resulting from the non-probability sample and sample size. This limits the generalisability of the findings to other CYPF and HCPs, although similar determinants to the management of T1DM are likely to exist. We also recognize that the CYPF who engaged with the evaluation were more likely to be those using the app and were a self-motivated sample. Recruiting those not using the app, although difficult, would have provided a different perspective. This evaluation did not include an economic evaluation, which was not within the scope of this study but was conducted in a separate investigation [32]. Furthermore, this study did not assess the impact of the app on different insulin modalities or perform a comparative research design, so these are considerations for future investigations. People signed up to use the app on an individual basis, but we do not know if single accounts were accessed by multiple members of the same family. Not all app users participated in the evaluation. The app evaluation only covered five sites, so the generalisability of the findings might be limited. In addition, future investigations might assess cohorts in a prospective pattern comparing the knowledge, psychological condition, quality of life, and glycaemic control of the studied cohort before and after the use of the app.

The limitations of the evaluation are balanced by strengths and include the adoption of a mixed-methods evaluation design that collected quantitative and qualitative data at multiple NHS sites across England. The quantitative data were combined with qualitative data from four of the five sites to provide detailed insight into the impact and implementation of the DigiBete app. Furthermore, the evaluation is, to the best of our knowledge, the only service-level evaluation of an innovative app for helping CYPF and HCPs to improve the management of their T1DM. The accounts of CYPF and HCPs provided rich information on the impact and implementation of the app, including what works well and why and, importantly, what does not work as well and why, as is called for in the literature [14], this is important in improving interventions for CYPF with diabetes. The involvement of CYPF and HCPs in the evaluation is important in helping to improve the effectiveness and delivery of T1DM interventions [3]. With that in mind, information provided through the evaluation was shared with the developers of the DigiBete app in early 2023, so that refinements can be made to areas identified in this evaluation, that will help improve the care provided through the app. In doing so, this evaluation aspires to be beneficial and help improve the diabetes care of the CYPF who use the app. Moreover, our investigation provides insights into how we conducted this service-level evaluation that will be invaluable to other stakeholders contemplating and planning their own investigations.

5. Conclusions

T1DM is a major public health problem. However, structured interventions can help people living with the condition enhance their knowledge and skills and motivate them to take control and manage it effectively. In the understanding that face-to-face interventions are not ubiquitously effective, digital health interventions like DigiBete provide opportunities to optimise patient experience and outcomes while offering services in a more efficient way, reducing the burden on HCPs and proving cost effective.

Digital health interventions are proven to be effective in managing and preventing the occurrence of complications, improving self-efficacy [33], and facilitating improvements in HbA1c [34], especially when delivered through mobile apps or patient portals [35]. This evaluation found that the DigiBete app represents a trusted source of approved and regulated information, which provides a constant source of reassurance for CYPF. Moreover, HCPs validated DigiBete in helping CYPF to manage their T1DM while saving their service time and money. The evaluation was beneficial for informing learning [3,27] and also the delivery of the DigiBete app, that could subsequently shape future provision.

References

- Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF). Available online: https://www.jdfr.org.uk/information-support/about-type-1-diabetes/facts-and-figures/ (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes ATLAS, 9th ed.; IDF: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kime, N.; Zwolinsky, S.; Pringle, A.; Campbell, F. Children and Young People’s Diabetes Services: What works well and what doesn’t? Public Health Pract. 2022, 3, 100272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, N.C.; Beck, R.W.; Miller, K.M.; Clements, M.A.; Rickels, M.R.; DiMeglio, L.A.; Maahs, D.M.; Tamborlane, W.V.; Bergenstal, R.; Smith, E.; et al. State of Type 1 Diabetes Management and Outcomes from the T1D Exchange in 2016–2018. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2019, 21, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, L.; Maryniuk, M.; Beck, J.; Cox, C.E.; Duker, P.; Edwards, L.; Fisher, E.B.; Hanson, L.; Kent, D.; Kolb, D.; et al. National standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 2393–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health; National Paediatric Diabetes Audit. Spotlight Audit Report: Diabetes-Related Technologies 2017–2018; RCPCH: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Desrochers, H.R.; Schultz, A.T.; Laffel, L.M. Use of diabetes technology in children: Role of structured education for young people with diabetes and families. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 49, 10–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kordonouri, O.; Riddell, M. Use of apps for physical activity in type 1 diabetes: Current status and requirements for future development. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 10, 2042018819839298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.; Greenwood, D.A.; Blanton, L.; Bollinger, S.T.; Butcher, M.K.; Condon, J.E.; Cypress, M.; Faulkner, P.; Fischl, A.H.; Francis, T.; et al. National Standards for Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 1409–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonoto, B.C.; de Araújo, V.E.; Godói, I.P.; Pires de Lemos, L.L.; Godman, B.; Bennie, M.; Diniz, L.M.; Junior, A.A.G. Efficacy of mobile apps to support the care of patients with diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017, 5, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Xu, Q.; Diao, S.; Hewitt, J.; Li, J.; Carter, B. Mobile phone applications and self-management of diabetes: A systematic review with meta-analysis, metaregression of 21 randomized trials and GRADE. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018, 20, 2009–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DigiBete. Available online: https://www.digibete.org (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Programme Evaluation. 2016. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/evaluation/index.htm (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Eldredge, L.K.; Markham, C.M.; Ruiter, R.A.; Fernández, M.E.; Kok, G.; Parcel, G.S. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach, 4th ed.; JohnWiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 541–585. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. The National Evaluation of the Local Exercise Action Pilots; Crown: London, UK, 2007.

- The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Patient Experience in Adult NHS Services: Improving the Experience of Care for People Using Adult NHS Services; NICE: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kime, N.; Pringle, A.; Rivett, M.J.; Robinson, P.M. Physical activity and exercise in adults with type 1 diabetes: Understanding their needs using a person-centered approach. Health Educ. Res. 2018, 33, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, O.; Berry, A.; Joule, N.; Rayman, G. Inpatient diabetes care during the COVID-19 pandemic: A Diabetes UK rapid review of healthcare professionals’ experiences using semi-structured interviews. Diabet. Med. 2021, 38, e14442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearman, M. Eliciting rich data: A practical approach to writing semi-structured interview schedules. Focus Health Prof. Educ. A Multi-Prof. J. 2019, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, N. Doing template analysis. In Qualitative Organizational Research: Core Methods and Current Challenges; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; Volume 26, p. 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.; McCluskey, S.; Turley, E.; King, N. The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2015, 12, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brew-Sam, N.; Chhabra, M.; Parkinson, A.; Hannan, K.; Brown, E.; Pedley, L.; Brown, K.; Wright, K.; Pedley, E.; Nolan, C.J.; et al. Experiences of young people and their caregivers of using technology to manage type 1 diabetes mellitus: Systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. JMIR Diabetes 2021, 6, e20973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaslawi, H.; Berrou, I.; Hamid, A.; Alhuwail, D.; Aslanpour, Z. Diabetes self-management apps: Systematic review of adoption determinants and future research agenda. JMIR Diabetes 2022, 7, e28153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, D. Young people’s use of digital health technologies in the global north: Narrative review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e18286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, L.; Helland, M.S.; Holt, T. The impact of school closure and social isolation on children in vulnerable families during COVID-19: A focus on children’s reactions. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 1231–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, J.; Leary, A.; Walden, E.; Stanisstreet, D.; Punshon, G. The workload of the diabetes specialist nurse workforce in the UK. J. Diabetes Nurs. 2020, 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pringle, A.; Kime, N.; Lozano, L.; Zwolinksy, S. Evaluating interventions. In The Routledge International Encyclopedia of Sport and Exercise Psychology; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=pWDdDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT333&dq=A+Pringle,+N+Kime,+L+Lozano,+S+Zwolinksy&ots=qmFCJMhkFx&sig=xKOp4t4WWgU7P0oyocLPVPLc7gE#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- Norman, B. How family expectations change a healthcare organization. McNights Long Term Care News. 2016. Available online: https://www.mcknights.com/blogs/guest-columns/how-family-expectations-change-a-healthcare-organization/ (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- Desborough, J.; Parkinson, A.; Lewis, F.; Ebbeck, H.; Banfield, M.; Phillips, C. A framework for involving coproduction partners in research about young people with type 1 diabetes. Health Expect. 2022, 25, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, K.; Uddin, R.; Ridgers, N.D.; Brown, H.; Veitch, J.; Salmon, J.; Timperio, A.; Sahlqvist, S.; Cassar, S.; Toffoletti, K.; et al. The use of digital platforms for adults’ and adolescents’ physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic (our life at home): Survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e23389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Move Consulting Do Digital? Available online: https://moveconsulting.co.uk/blog/f/do-digital (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- York Health Economics Consortium. Cost-Effectiveness Model of the DigiBete Digital App for Children and Young People with Type 1 Diabetes Report; York Health Economics Consortium: York, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Garner, K.; Boggiss, A.; Jeffries, C.; Serlachius, A. Digital health interventions for improving mental health outcomes and wellbeing for youth with type 1 diabetes: A systematic review. Pediatr. Diabetes 2022, 23, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, S.; Gallagher, S.; Andrews, T.; Ashall-Payne, L.; Humphreys, L.; Leigh, S. The effectiveness of digital health technologies for patients with diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Front. Clin. Diabetes Healthc. 2022, 3, 936752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkhoma, D.; Soko, C.; Bowrin, P.; Manga, Y.; Greenfield, D.; Househ, M.; Li Jack, Y.; Iqbal, U. Digital interventions self-management education for type 1 and 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 210, 106370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]