1. Introduction

Despite public health efforts, US suicide rates have been increasing steadily over the last 20 years, with steeper increases occurring more recently [1,2]. Data from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health indicated that among adults aged 18 or older in 2020, 12.2 million people had serious thoughts of suicide, 3.2 million people made a suicide plan, and 1.2 million people attempted suicide in the past year. In 2020, of those between the ages of 12 to 17, 3.0 million people had serious thoughts of suicide, 1.3 million people made a suicide plan, and 629,000 people attempted suicide in the past year [3]. Suicide is the second leading cause of death among ages 10 to 34, the fourth leading cause among ages 35 to 54, and the eighth for adults aged 55 to 64 [4]. This trend has been observed for all age groups, although in recent years the rates for young adults (ages 25–44) have surpassed that of adults aged 65 and older [1,5].

Rural communities in the US bear a disproportionate burden when it comes to suicide mortality, as rates are higher in rural areas than in urban ones [6]. Further, rates have been increasing more quickly in rural areas [7,8], contributing to widening rural health disparities [6]. The difference in suicide rates between rural and urban areas has widened from 1999 to 2017, increasing by 53% in rural areas when compared to only 16% in urban areas [9]. Specifically, suicide rates in rural areas have been higher and have continued to accelerate more quickly since 2007 [10]. Georgia is no exception to this trend, with 2021 data revealing an age-adjusted death rate due to suicide of 18.4 per 100,000 persons in rural Georgia counties compared to 14.2 in non-rural counties [11].

Suicide mortality reflects only a fraction of the burden on individuals and communities. Suicidal ideation and plans often lead to attempts, which are costly and more numerous than suicide deaths [1,12]. In 2018, almost 450,000 adults were hospitalized on at least one night for a suicide attempt—almost 10 times the number of deaths [12]. Additionally, 717,000 adults received medical attention for an attempt, and almost 1.5 million adults self-reported an attempt [12]. Therefore, when assessing the burden of suicide in a community, it is essential to consider suicidal ideation and behavior, in addition to suicide mortality. Unfortunately, regular and reliable surveillance data on non-lethal suicidal behavior are usually not available for rural areas, but it is probable that this disparity exists for suicidal ideation and behavior as well.

In addition to higher suicide rates, rural areas face unique contributors to suicide and barriers to suicide prevention in the form of cultural, social, and economic factors [10]. The aforementioned increased rates in rural counties have been linked to higher deprivation, higher social fragmentation, lower social capital, the higher availability of gun shops, and a greater proportion of veterans and an uninsured population residing within a county [7]. Culturally, access to firearms likely plays a role in elevated rural suicide rates. One study on gun owners found that those who owned a firearm for protection were less likely to engage in lethal means safety practice, more likely to store their firearm loaded, and were less likely to believe that firearm ownership and storage practices were linked to the risk of suicide [13], highlighting the importance of gun culture in rural areas.

Structural barriers to accessing care are also important. For example, access to specialty mental health care providers is limited due to the sparse number of providers in rural areas, as well as the lack of transportation [14,15]. This can affect suicide, as one US study found that for every 10% increase in the mental health workforce, there was a 1.2% reduction in firearm suicides [16]. Access to emergency medical facilities, often the place where suicide attempts are treated, is also limited [17].

Incorporating qualitative research into suicide prevention is essential, as it can illuminate the complex constellation of risk and protective factors that affect suicidal acts and behavior [18]. Qualitative research can also offer deeper understandings of the structural contexts (e.g., geographical, policy, service use landscape) in which prevention efforts take place [18]. This stands in contrast to quantitative studies, which often focus on explanation of phenomena (e.g., causal relationships) [18]. Unfortunately, qualitative studies reporting community-based suicide prevention efforts are sparse, particularly in the US. Existing international work underscores barriers, such as stigma or aspects of rural culture [19,20], or reinforces addressing barriers, such as healthcare shortages [21]. Efforts must be community-led and engage the entire community, not just clinical professionals, leveraging partnerships [22]. Such work must identify and address self-identified community needs [22], but also use trauma-informed strategies [19].

Role of Community-Based Suicide Research

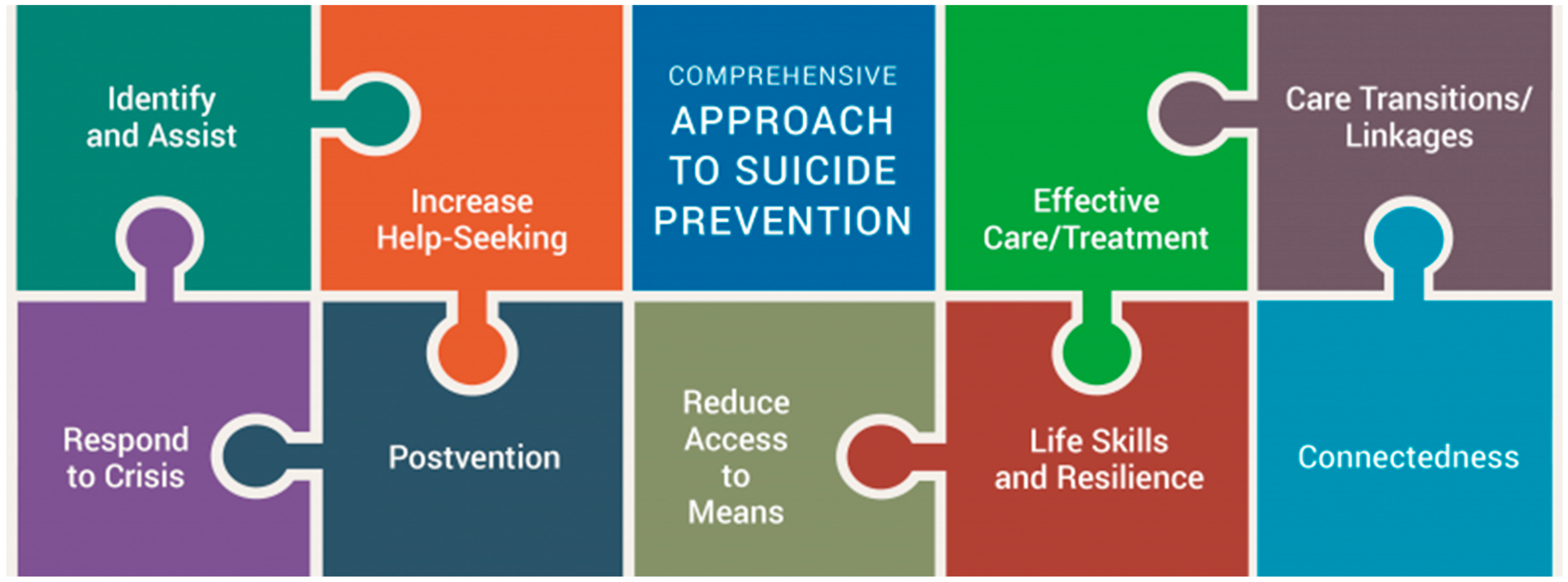

Suicide is a multi-faceted and multi-level problem; therefore, a social–ecological perspective [23] is useful when trying to understand its determinants in a specific community context. The Suicide Prevention Resource Center (SPRC) recommends a comprehensive approach to suicide prevention for it to be effective, which typically requires “a combination of efforts that work together to address different aspects of the problem” [24]. It contains several strategies, programs, and practices to consider, spanning several socio-ecological levels (i.e., from individual to systems-level solutions) [23].

Tailoring preventive interventions to specific contexts and communities is essential, yet often this crucial step is overlooked [25]. Although the available county-level data can provide some broad insight into possible contributing factors (e.g., high poverty and unemployment rates), qualitative data from a community perspective can provide a deeper and more nuanced understanding of who in the community is struggling and potential ways to support them. Qualitative data provide a rich picture of the community context from the perspective of community members, so that any suicide prevention effort will be appropriate for that community.

This study gathered the necessary formative research through in-depth qualitative interviews and focus groups to successfully adapt the most appropriate preventive intervention to the population and context. Specifically, we aimed to: (1) gain a deeper understanding of the perceived problem as it relates to suicide and suicidality in the county; (2) understand the unique community context of the county as it relates to suicide and suicidal behavior, with a focus on identifying previous or existing suicide prevention efforts in county and key informants who are instrumental in implementing or enhancing such efforts; and (3) assess the feasibility and accessibility of implementing different rural suicide prevention efforts, including identifying barriers to their success. This formative research project will lay the essential groundwork for future prevention work in which a feasible and acceptable suicide preventive intervention will be implemented to reduce suicide and suicidal behavior in the identified high-risk group(s).

2. Materials and Methods

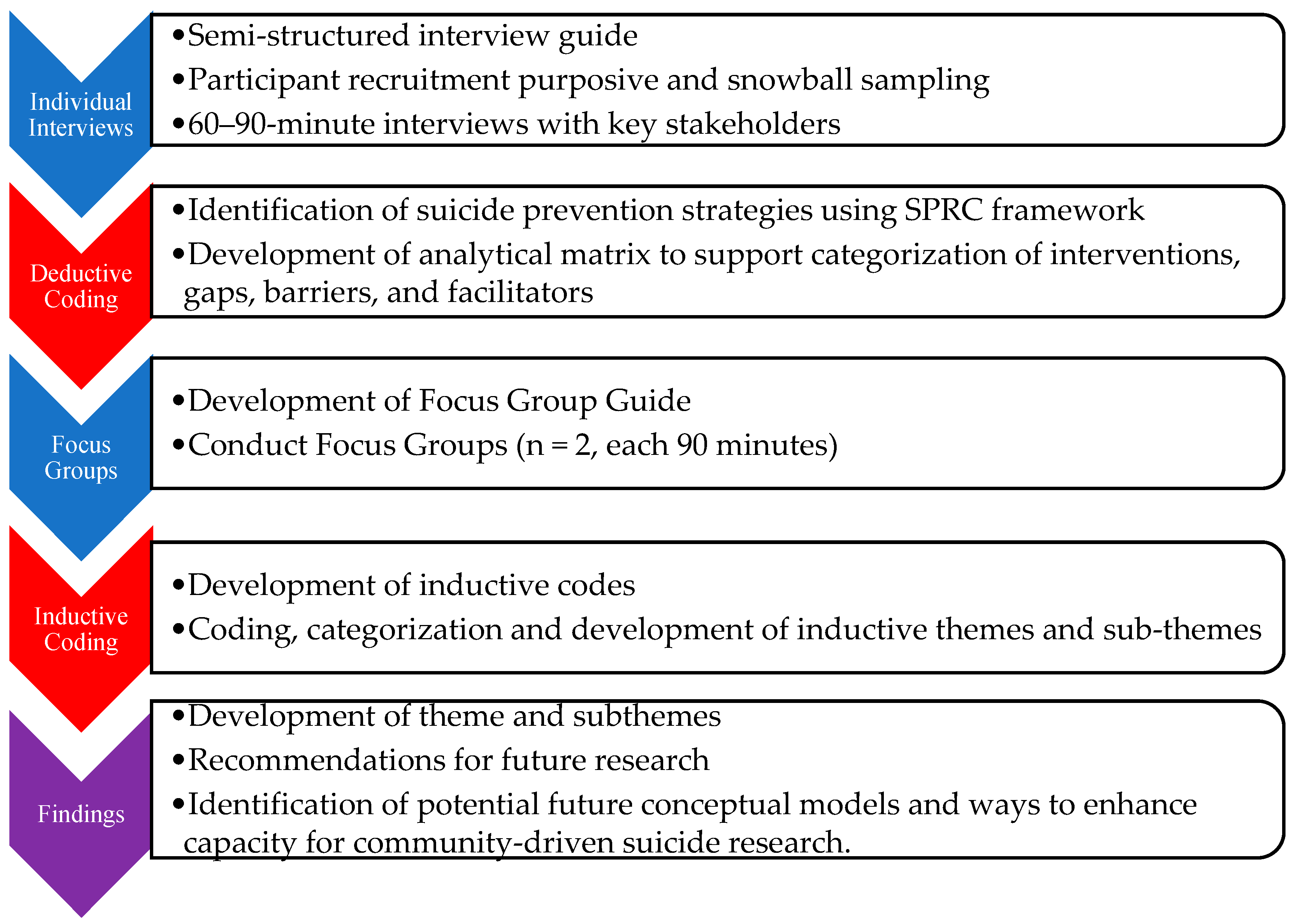

This is a community-based qualitative study using both in-depth interviews and focus groups. Figure 1 displays a visual flow chart of the data collection and analysis process.

Figure 1. Flow Chart of Study Data Collection and Analysis Processes. Note: data collection activities are shown in blue and analyses are shown in red.

2.1. Setting

The study county, located in Georgia, is a relatively small, rural county with a military base that is a prominent part of the local economy and county members’ livelihood. This county is no exception to the disproportionately high suicide rates in rural areas, ranking fourteenth in suicide mortality in the state [26]. Suicide was in the top 10 leading causes of death in the county in 2015–2019, and ranked as the top cause of years of potential life loss [26], indicating that younger residents are dying by suicide. In 2019, there were 15 suicide deaths, amounting to a death rate of 24.4 per 100,000 residents—60% higher than the state average [26]. The suicide rate has increased 2.5-fold since 2000, an increase much more dramatic than that observed for the state as a whole [26]. Because of the lack of additional county-wide data, it is essential to gain a deeper understanding of the scope of the problem (regarding fatal and non-fatal suicidal behavior) in the community and the subgroups within the community that are experiencing the highest need in order to identify the most appropriate program or intervention to address the high suicide rates in the county.

2.2. Participants and Data Collection

Data collection occurred from August 2021 to June 2022.

Individual data collection consisted of 20 semi-structured one-on-one interviews with 22 community stakeholders, purposively selected from the community and through snowball sampling. Recruitment involved contacting potential participants by email and/or phone. In order to be eligible for participation, individuals had to be over 18 years of age, living and/or working in the study county, and interested in discussing the topic of suicide in the community. To ensure coverage across the entire community, we identified five broad sectors of stakeholders and contacted individuals with leadership positions in those sectors who might have insight into the problem. We asked all participants, regardless of willingness or ability to participate, to recommend additional community members that we should talk to. Interview participants primarily came from the non-profit/religious sector (n = 7, 32%), followed by the healthcare (n = 6, 27%), education (n = 5, 23%), military (n = 2, 9%), and government (n = 2, 9%) sectors. The majority of participants were female (73%), with an average age of 51.7 years of age. Fifteen individuals were living in the county (an average of 19.1 years of residence), and six worked in the county but lived elsewhere (an average of 12.5 years worked).

Senior members of the research team (who have expertise in suicide prevention, qualitative research, psychiatric epidemiology, social work, sociology, and lived experience in suicide prevention research) developed a semi-structured interview guide to align with our goal of gaining a deeper understanding of the scope of the problem, including which members of the community are struggling and the community context. We explored interviewees’ views on contributing and protective factors that may affect the high suicide rate and what they want to see changed in their community. Interviews were carried out by two members of the senior research team and research assistants. Research assistants were medical students at Mercer University from a wide range of backgrounds, including both rural and urban contexts, including rural Georgia. Prospective participants were not contacted more than three times. Interviews were conducted either in person or via Zoom, depending on the interviewee’s preference, and lasted approximately 60 to 90 min. All interviews were recorded and later transcribed by a member of the research team using Transcribe [27]. Interviewers memoed their experience post interview to allow the research team to ground the context in which the data were collected.

Focus group members were recruited from participants in the individual interviews as well as other stakeholders interested in implementing a community-based suicide prevention effort, as identified through the in-depth interviews. All interviewees were invited to participate in the focus groups. Snowball sampling was also employed for focus group recruitment. Focus group guides were informed through the deductive analysis of individual interviews and reviewed by senior members of the research team. Focus groups consisted of 6 to 10 participants who identified as a stakeholder in suicide prevention efforts in the community. Sessions lasted approximately 1.5 h, were conducted in person, and were led by two members of the research team. Sessions were audio recorded and transcribed in the same manner as the semi-structured interviews. In addition to audio capturing the focus group sessions, a third research team member memoed their observations, interactions, and experiences during the focus group sessions. Participants received a USD 50 Amazon gift card for their participation in the interviews or focus groups.

2.3. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using a two-step deductive and inductive content analysis adapted from Elo and Kyngäs [28] and Sandström et al. [29] (see Figure 1). Content analysis is a flexible analysis method that involves the distilling of textual data into categories or themes and is helpful for drawing connections from data to context, simplifying a broad phenomenon, and developing new insights and actions [28]. This process allowed development of themes and subthemes that are both conceptually driven (deductive) and derived from the data (inductive) [30,31]. Both rounds of coding were conducted in Dedoose 9.0.17 [32].

Phase I deductive coding used the SPRC’s Comprehensive Approach to Suicide Prevention (hereafter, SPRC framework) to distill the data into more concise meaning units or excerpts [33] and organize these excerpts into one of nine intervention types identified by the SPRC framework (see Figure 2 for the nine intervention types). Members of the study team then conducted a sorting exercise adapted from Sandström et al. [29], in which excerpts were sorted into whether they described existing resources/facilitators or barriers/gaps or could not be sorted. Reflections on the exercise and excerpts that could not be sorted and why were then discussed with members of the research team. Deductive findings contributed to materials for the focus group discussion, where participants were presented with intervention types that came up most often and sample quotes for different intervention types.

Figure 2. Elements of a Comprehensive Approach to Suicide Prevention. Note: taken from the Suicide Prevention Research Center’s website: https://sprc.org/effective-prevention/comprehensive-approach (accessed on 21 September 2023).

Phase II inductive codes were developed through memoing and discussion during the deductive Phase I of coding. The process of memoing in qualitative data collection and analysis allows the researchers to reflect on the process, helps shape codes and themes, and allows for further thought about new connections to facilitate deeper understanding [34]. Additionally, open coding of the focus groups contributed to the refinement of the codes and sorting codes into categories, subthemes, and themes. The development of findings was an iterative process in which researchers discussed each step of the data collection and analysis and how they built upon each other, as well as what is known from the literature. As part of the entire iterative process, the authors reflected on their own positionality in relation to the data as mental health and community health researchers and medical students, as well as how their own biases toward desired outcomes and perspectives may have affected the interpretation of the data.

3. Results

Three themes emerged from the data: (1) cumulative trauma and isolation; (2) support networks and systems; and (3) treatment gaps and community response . Theme 1, cumulative trauma and isolation, illuminates perceived contextual drivers of suicide in the county, including how individuals, families, and the county are responding to crisis and geographic isolation (subtheme 1.1), as well as a substantial loss of life due to death by suicide in the community. Theme 2, support networks and systems, illustrates how access to suicide prevention in rural areas is not universal but dependent on connection to formal (i.e., health and mental health care; subtheme 2.1) and informal (i.e., family and friends) systems and resources (subtheme 2.2). Finally, Theme 3, treatment gaps and community response, illustrates gaps in long-term mental health care, crisis services, and postvention (subtheme 3.1) and grassroots community efforts to provide community and postvention support (subtheme 3.2).

3.1. Theme 1: Cumulative Trauma and Isolation

In this theme, participants gave insight into the perceived contextual drivers of suicide. Two subthemes, 1.1 community crisis and 1.2 survivors of suicide loss, illustrate how the rural county context exacerbates known drivers of suicide, such as exposure to family violence, trauma, substance use, and economic crisis. Specific rural contexts that are explored in this theme include isolation, rural-specific patterns in substance use and economic crises (e.g., homelessness), and small social networks with high proportions of suicide loss survivors. In addition to exposure to known risk factors, these contexts also contributed to barriers of known protective factors, such as connectedness and social support, reduced capacity for resilience, as well as a need for increased community postvention services. Postvention involves activities, such as providing evidence-based services, to reduce risk and facilitate healing in the wake of a suicide death.

3.2. Theme 2: Support Networks and Systems

Theme 2 illustrates how a connection to formal public systems (subtheme 2.1) and reduced availability of family resources, including knowledge and finances (subtheme 2.2), contribute to access to suicide prevention interventions. This theme illustrates perceived supportive resources in the county, with many evidence-based interventions mentioned by providers in schools or connected with the military base/VA combined. Many providers mentioned gaps in family resources financially and socially, with stigma as a salient barrier to accessing care. Thus, this theme expands upon the contextual drivers of death by suicide (Theme 1) and illustrates how it is not only exposure to trauma that reduces resources; there are also larger implications for suicide prevention access. Deductive coding highlighted specific SPRC framework areas salient to this theme, largely implemented in schools: identify and assist, crisis response, long-term mental health care, life skills and resilience, and connectedness and social support.

3.3. Theme 3: Treatment Gaps and Community Response

Theme 3 highlights gaps in suicide prevention interventions (subtheme 3.1) in the county and how community stakeholders aim to fill these gaps (subtheme 3.2). As discussed in Theme 2, access and barriers to suicide prevention interventions described by participants were dependent on institutional and family connections. In contrast, Theme 3 illustrates gaps and needs following the development of a safety plan (i.e., a written list of coping strategies and sources of support to be used in a suicidal crisis) as part of an intervention such as ASIST [37]. The SPRC framework intervention areas of care transitions and linkages, long-term mental health care, post intervention, and responding to individuals in crisis all relate to this theme. Community-conceived responses to these gaps include strengthening community collaboration.

4. Discussion

This study used qualitative methods to conduct formative work necessary to tailor suicide prevention and postvention programming for this unique rural community. Through semi-structured interviews and focus groups, we identified three overarching themes: cumulative trauma and isolation, support networks and systems, and treatment gaps and community response. These themes highlighted important contextual drivers of suicide in the community, populations with strong supports in place, specific barriers to care, as well as a systems-level assessment of weak points in the crisis care continuum.

Broadly, many of the identified themes and sub-themes are consistent with current literature. For example, in an era where social determinants of health are gaining more attention, our results that economic crises are perceived as drivers of community suicides underscore the importance of addressing more than individual behaviors and mental illness—two factors that have traditionally received much more attention in the literature [41,42]. This also highlights the need to consider suicide and its prevention from a socio-ecological perspective. Conceptual frameworks like Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory [23] provide a foundation for understanding the drivers of suicide and using a multilevel approach to address it. Our results confirm this by highlighting both drivers and supports at the family, peer, and organizational level. Finally, rural-specific factors such as stigma and lack of available providers also rose to the top in our results. These factors are barriers consistently discussed in the literature when considering mental health care in rural areas [43]. Further, the linkage gaps in the mental health care system that were discussed are representative of nationwide system gaps (e.g., staff shortage, burnout, long waitlists/lack of beds, siloed provider communication), but other factors like long travel times are more prevalent in rural communities.

Similarly, the lack of certain themes should be noted. First, there was no mention of access to firearms as a driver of suicide, or limiting access as a possible prevention strategy. This stands in stark contrast to the evidence that one of the most effective ways to reduce suicide is to reduce the lethality of attempts [10], compounded with evidence that individuals in rural areas are more likely to choose to die by firearm [44], which is the most lethal method [45]. Second, although a wide variety of factors were described when participants discussed drivers of the suicide problem in the county, mental illness was rarely explicitly mentioned as a cause of suicide. Although suicide is a multifaceted problem, many studies show that mental illness is a precursor to suicidal thoughts and behaviors [41]. Third, the lack of emphasis on postvention is striking, especially given the small, highly interconnected community. Postvention has long been promoted as a way to prevent suicide among suicide survivors—those who have lost a loved one by suicide and, as a result, are at an increased risk of suicide themselves [46]. Some have argued that postvention is so essential to suicide prevention that any program must include a postvention component [47].

We also saw some themes that likely arose from the unique community context of this rural Georgia county. Although we saw recurring themes that are common among rural communities (e.g., stigma, lack of healthcare providers) [43,48], the county has unique factors that affect the context in which suicide drivers and prevention take place. Most salient is the military base located within its borders, not only creating a high percentage of service members, veterans, and their families—which we know have higher suicide rates than the general population [49,50]—but also a transience and sense of isolation that respondents felt were more prominent in the county. There was also a realization of a fair number of programs available, particularly if you were connected to the school system or military, but that these initiatives and available providers were extremely siloed.

Our findings have important implications for next steps. First, there appears to be a place for capacity building in this community. Chaskin [51] defines community capacity as “the interaction of human, organizational, and social capital existing within a given community that can be leveraged to solve collective problems and improve or maintain the well-being of a given community. It may operate through informal social processes and/or organized efforts by individuals, organizations, and the networks of association among them and between them and the broader systems of which the community is a part”. In this context, capacity is a community’s ability to address the suicide problem and/or implement and enhance suicide prevention efforts. Respondents talked about capacity in both an individual/emotional as well as an institutional/structural manner. In particular, some structural dimensions of Chaskin’s framework were highlighted, such as the current limited capacity in facilities (e.g., not enough inpatient beds) and the limited communication across sectors. In light of this, a reasonable next step would be a county-wide inventory of available services across the crisis care continuum, such as the Crisis Intercept Mapping process that the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) undertakes in for suicide prevention among service members, veterans, and their families. This is a locally driven approach to strengthen a community’s coordination of crisis care, stakeholder partnerships, and delivery of evidence-based suicide prevention policies [52]. Such an approach could help address the siloed efforts that are unevenly distributed in this county and identify gaps and barriers to crisis services.

Second, it is clear more rural-focused suicide preventive interventions and postventions are needed. The identified themes can help move these evidence-based interventions forward. Strikingly, the community must undertake this while still grieving from suicide loss. At least three different levels of responses are needed: universal prevention to inform the community about suicide risk and to help address stigma; communication pathways between providers and institutions, and resource lists for the community when intervention is needed; and community healing via postvention so that individuals can process a loss. Taken together, these things would help fill the identified gaps in a community that is actively trying to mobilize around suicide prevention.

Limitations

Despite its strengths, this study was not without limitations. We used snowball sampling, which may lead to a biased sample, but it allowed us to recruit key stakeholders across multiple domains. A couple of interviews experienced technical difficulties, making parts difficult to transcribe due to glitches or noise. While we conducted an adequate number of interviews for a small qualitative study, we were relying on a relatively small number of people in each stakeholder domain; thus, themes arising from their subjective perspectives on the subject matter may have differed if we had interviewed more people per domain. We had a finite number of people in these different domains, and likely missed important groups. For example, military and non-mental health services were under-represented in our sample.

5. Conclusions

This study laid the essential groundwork to address high suicide rates in a community where stakeholders across a variety of sectors recognize the need for prevention and intervention. Knowing the unique community context is critical in order to tailor such prevention programming to meet the specific needs of a rural community, which in and of itself presents unique challenges. Although many themes support the existing knowledge base in the literature, understanding perceived drivers and existing gaps will help guide intervention selection. There is also a readiness at the grassroots level to address the problem, yet it has been difficult to gain traction in building a suicide prevention coalition. Because suicide is a multifactorial problem, it is important to take a holistic approach, incorporating multiple social–ecological levels, when building and tailoring prevention programming.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health. Statistics 1999–2018 Wide Ranging Online Data for Epidemiological Research (WONDER); Multiple Cause of Death Files [Data File]; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020.

- Hedegaard, H.; Curtin, S.C.; Warner, M. Increase in Suicide Mortality in the United States, 1999–2018; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2020.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health; NSDUH Series H-56; Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). 2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center. Suicide by Age. Available online: https://www.sprc.org/scope/age (accessed on 26 May 2021).

- Kegler, S.R.; Stone, D.M.; Holland, K.M. Trends in Suicide by Level of Urbanization—United States, 1999–2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2017, 66, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steelesmith, D.L.; Fontanella, C.A.; Campo, J.V.; Bridge, J.A.; Warren, K.L.; Root, E.D. Contextual Factors Associated with County-Level Suicide Rates in the United States, 1999 to 2016. JAMA Netw/Open 2019, 2, e1910936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivey-Stephenson, A.Z.; Crosby, A.E.; Jack, S.P.D.; Haileyesus, T.; Kresnow-Sedacca, M. Suicide Trends Among and Within Urbanization Levels by Sex, Race/Ethnicity, Age Group, and Mechanism of Death—United States, 2001–2015. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2017, 66, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedegaard, H.; Curtin, S.C.; Warner, M. Suicide Mortality in the United States, 1999–2017; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2018.

- Barnhorst, A.; Gonzales, H.; Asif-Sattar, R. Suicide Prevention Efforts in the United States and Their Effectiveness. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2021, 34, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgia Department of Public Health. Online Analytical Statistical Information System (OASIS). Mortality Web Query. Available online: https://oasis.state.ga.us/oasis/webquery/qryMortality.aspx (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables; Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2019.

- Butterworth, S.E.; Daruwala, S.E.; Anestis, M.D. The Role of Reason for Firearm Ownership in Beliefs about Firearms and Suicide, Openness to Means Safety, and Current Firearm Storage. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2020, 50, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rural Health Information Hub. Barriers to Mental Health Treatment in Rural Areas. Available online: https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/mental-health/1/barriers (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Gamm, L.; Stone, S.; Pittman, S. Mental Health and Mental Disorders—A Rural Challenge: A Literature Review. In Rural Healthy People 2010: A Companion Document to Healthy People 2010; The Texas A&M University System Health Science Center, School of Rural Public Health, Southwest Rural Health Research Center: College Station, TX, USA, 2003; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, E.V.; Prater, L.C.; Wickizer, T.M. Behavioral Health Care and Firearm Suicide: Do States with Greater Treatment Capacity Have Lower Suicide Rates? Health Aff. 2019, 38, 1711–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, B.G.; Branas, C.C.; Metlay, J.P.; Sullivan, A.F.; Camargo, C.A. Access to Emergency Care in the United States. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2009, 54, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelmeland, H.; Knizex, B.L. Why We Need Qualitative Research in Suicidology. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2010, 40, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epp, D.; Rauch, K.; Waddell-Henowitch, C.; Ryan, K.D.; Herron, R.V.; Thomson, A.E.; Mullins, S.; Ramsey, D. Maintaining Safety While Discussing Suicide: Trauma Informed Research in an Online Focus Groups. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2022, 21, 16094069221135973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlbeck, S.A.; Quinn, K.; deRoon-Cassini, T.; Hargarten, S.; Nelson, D.; Cassidy, L. “I’ve given up”: Biopsychosocial factors preceding farmer suicide in Wisconsin. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2023, 93, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varia, S.G.; Ebin, J.; Stout, E.R. Suicide prevention in rural communities: Perspectives from a Community of Practice. J. Rural Ment. Health 2014, 38, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grattidge, L.; Hoang, H.; Mond, J.; Lees, D.; Visentin, D.; Auckland, S. Exploring Community-Based Suicide Prevention in the Context of Rural Australia: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979; ISBN 978-0-674-02884-5. [Google Scholar]

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center. A Comprehensive Approach to Suicide Prevention. Available online: https://www.sprc.org/effective-prevention/comprehensive-approach (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Baker, R.; Camosso-Stefinovic, J.; Gillies, C.; Shaw, E.J.; Cheater, F.; Flottorp, S.; Robertson, N.; Wensing, M.; Fiander, M.; Eccles, M.P.; et al. Tailored Interventions to Address Determinants of Practice. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, CD005470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgia Department of Public Health. Online Analytical Statistical Information System (OASIS). Available online: https://oasis.state.ga.us/oasis/webquery/qryDrugOverdose.aspx (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Wreally. Transcribe. [Software]. Available online: https://transcribe.wreally.com/ (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The Qualitative Content Analysis Process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, B.; Willman, A.; Svensson, B.; Borglin, G. Perceptions of National Guidelines and Their (Non) Implementation in Mental Healthcare: A Deductive and Inductive Content Analysis. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis; Flick, U., Ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2014; pp. 170–183. ISBN 978-1-4462-8224-3. [Google Scholar]

- Dedoose. Web Application for Managing, Analyzing, and Presenting Qualitative and Mixed Method Research Data. 2021. [Software]. Available online: https://www.dedoose.com/ (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative Content Analysis in Nursing Research: Concepts, Procedures and Measures to Achieve Trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, M.; Chapman, Y.; Francis, K. Memoing in Qualitative Research: Probing Data and Processes. J. Res. Nurs. 2008, 13, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, A.; Osborn, D.; King, M.; Erlangsen, A. Effects of Suicide Bereavement on Mental Health and Suicide Risk. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoMurray, M. Sources of Strength Facilitators Guide: Suicide Prevention Peer Gatekeeper Training; The North Dakota Suicide Prevention Project: Bismarck, ND, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- LivingWorks ASIST. Suicide Prevention Training Program. Available online: https://www.livingworks.net/asist (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Quinnett, P. QPR: Ask a Question, Save a Life; QPR Institute and Suicide Awareness/Voices of Education: Spokane, WA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention [AFSP]. Out of the Darkness Walks. Available online: https://supporting.afsp.org/?fuseaction=cms.page&id=1370 (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Goffman, E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity; First Touchstone; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1986; ISBN 978-1-4391-8833-0. [Google Scholar]

- Chesney, E.; Goodwin, G.M.; Fazel, S. Risks of All-Cause and Suicide Mortality in Mental Disorders: A Meta-Review. World Psychiatry 2014, 13, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turecki, G.; Brent, D.A. Suicide and Suicidal Behaviour. Lancet 2016, 387, 1227–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, J.K.; Cukrowicz, K.C. Suicide in Rural Areas: An Updated Review of the Literature. J. Rural Ment. Health 2014, 38, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, R.; Rehm, J.; de Oliveira, C.; Gozdyra, P.; Kurdyak, P. Rurality and Risk of Suicide Attempts and Death by Suicide among People Living in Four English-Speaking High-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Can. J. Psychiatry 2020, 65, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnour, A.A.; Harrison, J. Lethality of Suicide Methods. Inj. Prev. 2008, 14, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, R.T.P.; Slater, H. Suicide Postvention as Suicide Prevention: Improvement and Expansion in the United States. Death Stud. 2010, 34, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, J.R. Postvention Is Prevention—The Case for Suicide Postvention. Death Stud. 2017, 41, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S.K.; Cantrell, P.; Edwards, J.; Dalton, W. Factors Influencing Mental Health Screening and Treatment Among Women in a Rural South Central Appalachian Primary Care Clinic. J. Rural Health 2016, 32, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoge, C.W.; Castro, C.A. Preventing Suicides in US Service Members and Veterans: Concerns After a Decade of War. JAMA 2012, 308, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nock, M.K.; Stein, M.B.; Heeringa, S.G.; Ursano, R.J.; Colpe, L.J.; Fullerton, C.S.; Hwang, I.; Naifeh, J.A.; Sampson, N.A.; Schoenbaum, M.; et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Suicidal Behavior Among Soldiers: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry 2014, 71, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaskin, R.J. Building Community Capacity: A Definitional Framework and Case Studies from a Comprehensive Community Initiative. Urban Aff. Rev. 2001, 36, 291–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA]. Crisis Intercept Mapping for SMVF Suicide Prevention. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/smvf-ta-center/activities/crisis-intercept-mapping (accessed on 25 May 2023).