1. Introduction

Late childhood and early adolescence (about ages 9–12) are times of heightened emotional turbulence. Transitioning from childhood to adolescence presents many physical, intellectual, social developmental, and personality changes. This period can also see the onset of mental health issues, and one of the most common issues for young people is anxiety disorder [1].

In developed countries, an estimated nine per cent of young people experience anxiety disorders, and this is likely an underestimate [2]. Although some degree of anxiety and fear is normal and healthy for children, high levels of anxiety can cause considerable harm and distress to children and their families [3]. High and chronic levels of anxiety include excessive fear and related behavioural disturbances like avoidance behaviours or repeated actions to prevent a feared situation from occurring [3]. Anxiety can affect, among other things, the child’s physical health (headaches, stomach aches, trouble sleeping) and emotional health (fears of being laughed at or afraid to take part in events) [4]. Anxiety can also limit essential socialisation and increase feelings of isolation, affecting children, parents, and family.

If left unresolved, mental health disorders in childhood can have an enduring negative impact. Helping children in early adolescence may present an optimal opportunity to support and help young people with their mental health needs. Indeed, the long-term benefits are magnified when children receive treatment around the onset of an anxiety disorder [5].

Despite recent investments in youth mental health in Australia, young individuals typically have low engagement with mental health services. Estimates suggest that only about a third of young individuals with a mental disorder have received formal mental health care [6]. When care is accessed, it is often found to be inappropriate for them [5]. While youth mental health care has improved over the last few decades, systemic weaknesses in youth mental healthcare have resulted in missed opportunities for prevention and early help [7]. Beyond systemic weaknesses, long-held cultural attitudes about and stigma around mental illness and seeking help for mental illness create additional barriers to help [8]. The knock-on effect of stigma in mental illness effectively limits access to treatment with lifelong consequences for children [9]. Thus, the need for accessible, trusted, and non-stigmatising mental health interventions and support for children and early adolescents is urgent and vital.

Parents can play an essential role in the development, prolongation, and treatment outcomes of anxiety disorders in children [10]. However, for clarity and brevity of space, this paper does not consider the parents’ roles in contributing to or explaining their child’s anxiety, or otherwise. Rather, we focus on the parent’s perspectives of an arts-based intervention that aims to support their child’s wellbeing, which we describe below.

1.1. Arts Engagement and Mental Health

In the context of our research, arts engagement programs (AEPs) refer to non-clinical, structured programs led by artists and educators to support wellbeing [11]. AEPs have been found to reduce stress and anxiety, as well as increase confidence and self-esteem in adults [12,13]. AEPs take a broader approach to health care, incorporating aspects of mental health, including social inclusion, creativity, and enjoyment [14,15]. Evidence demonstrates positive outcomes in adults as a result of AEP interventions, including facilitating social inclusion, reducing anxiety and depression symptoms, increasing self-confidence, producing feelings of empowerment and wellbeing, and enhancing quality of life [11,12].

AEPs acknowledge that access to cultural and artistic pursuits can enhance health outcomes by fostering positive psychological, social, and behavioural responses [11,12,13]. These programs play a pivotal role in supporting mental health as they serve as a platform for self-expression, enabling individuals to convey their emotions, thoughts, and experiences in ways that may be difficult to express verbally. This connection to self, in turn, deepens an understanding of one’s emotions, nurturing wellbeing. Furthermore, engagement in arts-related activities, such as painting, drawing, dance, or music, can aid relaxation, diminish stress, and improve mood [14,15]. Participating in creative endeavours often requires focused concentration and immersion, facilitating a state of mindfulness. AEPs offer respite from daily routines to counteract negative thought patterns. They also contribute to a sense of achievement and bolster self-esteem and social connections, fostering a sense of belonging [11,12,13,14,15].

A study of an arts–mental health relationship found that adults who took part in two or more hours per week of arts engagement reported significantly better mental wellbeing than other levels of engagement [12]. Evidence demonstrates positive outcomes in adults as a result of these interventions, including facilitating social inclusion and belonging, reducing anxiety and depression symptoms, increasing self-confidence, producing feelings of empowerment and wellbeing, and enhancing quality of life [12]. Among the range of community options available, arts interventions are well suited to address the needs of young people.

Arts engagement for better mental health in young people encompasses a variety of genres, from circus [16] and creative writing [17] to visual art programs (our specific interest) [18,19], among others. However, the peer-reviewed evidence is sparse on the role of AEPs in youth mental health worldwide, a gap reduced by our research [20].

Among the few published articles including parents and children together in arts engagement programs to support children’s mental health, we identified few studies. In a remote Aboriginal community, Stock, Mares, and Robinson [21] found that a parent/child art and storytelling program engaged and connected parents and children, providing a platform for parents to reflect on various aspects of their own and their children’s journeys. Furthermore, Mak and Fancourt [19] determined that the positive impact of AEPs may be magnified if parents are included with the children. This study aims to add to these findings.

1.2. Culture Dose for Kids

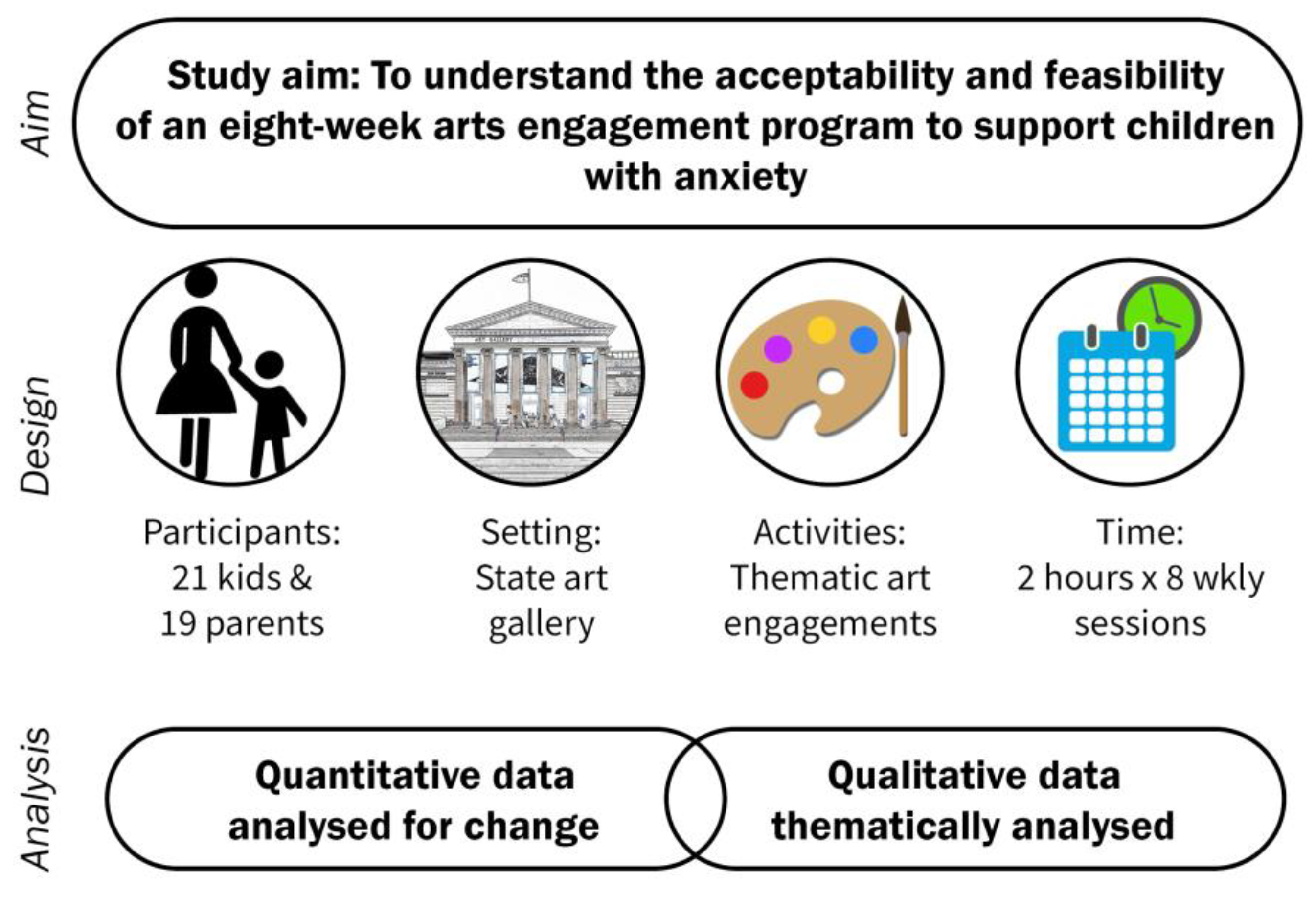

Culture Dose for Kids (“Culture Dose” is a play on words that combines two distinct concepts to create a catchy title for the program. “Culture” encompasses artful experiences. “Dose” refers to the way medicine is administered to achieve a certain effect. Thus, “Culture Dose” suggests the idea that experiencing cultural activities like arts engagement in a deliberate and controlled manner can have a positive impact on an individual’s wellbeing, similar to how a medicine dose can improve health) (CDK) is an AEP for young people experiencing anxiety and their parents/caregivers (from now on, parents). CDK was developed through collaboration between mental health researchers and art educators from the Art Gallery of New South Wales (Sydney) to support children with anxiety through weekly engagement with the arts in a gallery setting. Expert and experienced art educators guide and help young people connect to their feelings, thoughts, and imagination to build self-confidence and resilience. CDK is based upon a successful arts engagement pilot for adults with depression that showed a decrease in anxiety and depression and increased social inclusion [11]. CDK considers the child and parent in people–place–activity–time interactions to build upon community and family strengths. This paper examines the 2022 CDK pilot as a trial for use in a more extensive research program.

1.3. CDK Program

CDK took place over eight Saturdays in May and June 2022. The sessions included four segments: 45 min of guided, meditative, slow-looking (viewing an artwork for an extended time and discussing questions about the artwork as a group) at three thematic artworks (parents and children were in separate parallel sessions); morning tea; an hour of playful open-ended art creation together (inspired by the artworks they had just engaged with); and closing discussions and sharing art creations. Thematic content for each session was identified using an Australian longitudinal study that captured young people’s worries and concerns together with lived experience consultations [22]. Our published protocol paper provides a more detailed accompaniment to this section [23].

1.4. Research Aim

In this study, we sought to understand the parental perspectives (acceptability), feasibility (viability and practicality), and effectiveness of an eight-week AEP pilot at a state gallery for children with anxiety. The goal was addressed through qualitative (interviews, observations, and evaluations) and quantitative (anxiety scale and evaluative) measures. This program considered a people (parents and children)–place (gallery setting)–activity (the arts)–time (eight weeks) approach, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Culture Dose for Kids research design.

2. Materials and Methods

Our study design was informed by consultation with (a) parents with lived and living experience of their child’s anxiety; (b) in-house mental health experts in lived experience engagement; (c) child and adolescent mental health experts; and (d) the Art Gallery’s decades of experience running similar programs for diverse populations. This project was reviewed and approved by the University of New South Wales’ Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number: HC211020). Participant involvement in the study was voluntary. A study information sheet and consent form were provided at the outset of the research and informed consent was gained from participants prior to their participation.

2.1. Recruitment and Participants

After receiving ethical approval, recruitment occurred through social media in March 2022. After receiving 30 applicants who stated that their child was (1) experiencing mild anxiety (as identified by the parent); (2) in primary school, aged 9–12; (3) able to function in a group environment; and (4) able to take part in research, we closed the application process. All 30 applicants met the criteria and were accepted.

2.2. Participant Sample

Nineteen families from the Sydney metropolitan region attended and participated in the eight-week CDK research study, including 21 children (10 girls/11 boys) (22 children attended some sessions; however, 1 child withdrew after four weeks and 4 parents completed RCADS-P25 for the first session only). Two families had two children (each) participate. The mean number of sessions attended by children was six (a COVID-19 outbreak affected several sessions). Participants were not reimbursed for their participation.

2.3. Data Collection

This project used quantitative and qualitative research methodologies to collect data presented in . After consultation with in-house experts, our quantitative measures included evaluation ratings and the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale Parent version (RCADS-P25), which assessed the child’s anxiety and depressive symptoms from the parent’s perspective [24]. RCADS are efficient and reliable measuring tools designed for repeated use to evaluate anxiety and depressive problems in children over time [25]. RCADS-P25 is a widely used parent-reported questionnaire designed to assess symptoms of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. Its factor structure consists of 25 Likert-type questions corresponding to a specific type of anxiety or depressive symptom [25]. The scale’s reliability is evaluated through internal consistency and test–retest stability, both of which contribute to its validity as a measure of anxiety and depression symptoms in children [24,25]. Although the RCADS-P tool measures depression levels, we were not focused on depression in this study and have not included this construct in our paper.

RCADS were offered to parents on three occasions: at the first and last sessions, with a follow-up administered three months later by email. RCADS were employed to measure change over time, not to diagnose any disorder. We report on the anxiety component only in this study.

In addition, we collected quantitative data from parents through anonymous evaluation forms, asking questions about the program’s acceptability. Questions centred around their experiences of CDK and its impact on their wellbeing and social connectedness and whether they would recommend CDK to other parents with children with anxiety as an acceptable intervention.

Qualitative enquiry can enhance findings by encompassing and illustrating the complexity of human health and social behaviours [26,27]. Qualitative methods included interview questions and evaluation questions . On the advice of the parents, the children were not interviewed. The parents believed one-on-one interviews would be too confrontational for the children. In addition, the first author recorded her observations immediately following each session, focusing on context, processes, and interactions.

2.4. Analysis

Four data sources were analysed: interview transcripts, observational notes, written anonymous evaluations, and RCADS-P25 scores.

3. Results

This study aimed to determine CDK’s acceptability by parents, its feasibility—its viability and practicality—and its effectiveness.

3.1. Quantitative

The RCADS-P25 scores indicate that the program is an effective intervention to support children’s mental health as it relates to anxiety. Analysis of the RCADS-P25 scores indicates a significant reduction in anxiety. RCADS-P25 results included a baseline (M/SD) of 15.2 (5.3) and a post-intervention (M/SD) of 10.3 (2.9), resulting in p-values that were <0.001. The findings revealed that the program positively and significantly impacted parental perceptions of their child’s anxiety. In addition, anonymous parental evaluation data indicated a high level of the program’s acceptability, as shown in .

The above quantitative results signal that CDK’s design, processes, and intervention activities were appropriate from the perspective of the parent. Consistent attendance rates and evaluation scores suggest that CDK is also an acceptable and feasible intervention to support children’s anxiety. These quantitative findings show promise. However, within the qualitative results, we find nuanced and rich stories to further support CDK as an effective, feasible, and acceptable intervention.

3.2. Qualitative

Following these quantitative results, qualitative data, including observational notes, participant textual evaluations, and interview data, were thematically analysed. After repeated engagement with the data, our findings were organised into four central themes: connections, a safe space, creative activities to make mistakes, and changes in mood over time. Direct quotes and written statements support our findings to illustrate themes through personal and social contexts.

4. Discussion

This study aims to understand CDK’s effectiveness, acceptability, and feasibility (viability and practicality) with children with anxiety through their parents’ perspectives and feedback. Our inclusion of quantitative and qualitative analysis increases the robustness of determining whether CDK is a practical, viable, effective, and acceptable mental health support for children with anxiety.

The quantitative parental RCADS results indicate an improvement in their child’s anxiety levels as a direct outcome of the project, signalling its effectiveness. In addition, when examining the evaluation form results, all parents view CDK as a resource they would recommend to another parent to support a child who experiences anxiety. These two findings, taken together, indicate a high level of CDK’s effectiveness, acceptability, and feasibility by parents.

Notwithstanding these quantitative results, a more nuanced understanding of CDK’s impact on the child and parent can be understood through qualitative enquiry. This approach embraces the complexity of human health and social behaviours to enhance research findings [26,27]. Our findings, organised through people–place–activity–time themes, mirror the approach to creating CDK. The interaction of CDK components—who takes part, where it is located, what takes place and how, over eight sessions—build upon each other to strengthen the program and results.

The program facilitates a safe place and time for parents and children to be reflective and creative together to broaden and deepen parent–child bonds. CDK creates extended moments of calm to connect parent and child, providing parents with opportunities to explore their children and themselves in new ways to foster understanding, echoing Stock et al.’s [21] findings. Galleries are social institutions that promote personal growth and wellbeing through a deeper sense of the self and one’s surroundings, circumventing the stigmatisation of a clinical or therapy setting [15,23]. Situating CDK in a gallery creates a calming, reflexive space to increase the sharing of ideas, activities, experiences, and conversations to increase parent–child connectedness.

Our findings illustrate depictions of improved mood, confidence, and sense of empowerment in the child, qualities associated with resilience and mental wellbeing [14,20]. Open-ended activities provide opportunities for connection, creativity, and experimentation—sources of strength for improving mental health [20]. Comments from the parents signify that CDK creates a change in mood and attitude that lasted beyond the immediacy of the program. Indeed, one mother emailed us a month after the program ended, writing the following about her son’s school report: “two words which were phenomenal to see printed! These words were ‘resiliency’ and ‘confidence’! Two such attributes that have never been associated with [him] and I am almost certain that [CDK] was the main instigator of these”.

Early interventions can improve young people’s lifelong mental health and wellbeing [5]. By engaging both parent and child in this inclusive, non-stigmatising arts-based mental health intervention, a safe and creative community approach to support wellbeing occurred for child and parent. Our results reinforce Mak and Fancourt’s [19] findings that the positive impact of AEPs may be magnified if parents are involved in arts activities with their children. Our findings reflect the complex interactions of people–place–activity–time in the program. By this, we mean that CDK takes place in a peer group setting in a calming, meditative space (gallery) with reflective and creative activities that encourage story sharing over an extended period to build connections to inner thoughts, feelings, family members, peers, the gallery, artworks, and creativity. The program’s components interact and build off each other to produce positive mental health outcomes for participants.

Limitations

As this study was a pilot program, our findings were limited to a small group of urban children and families. Participation in CDK was established by parental belief that their child experienced anxiety (RCADS were not used to diagnose). Three-month RCADS follow-up had a low response rate, which, in future studies, we will incentivise with art gift packs. Furthermore, given the focus on supporting child anxiety, the authentic voice of children is absent in the paper. Instead, this paper’s findings are derived chiefly from mothers’ perspectives. In addition, while many parents responded that CDK was a great “reset” for them and their children, a quantitative measure of parental wellbeing before and after the program is missing.

In future CDK programs, we plan to tap into children’s experiences in more creative ways, befitting the ethos of this study. We will also quantitatively measure parents’ wellbeing levels to understand the impact of CDK on them. We acknowledge the limitations of the current research, thereby warranting further studies with a control group and improved longer-term follow-up to establish reliable causality and longitudinal findings.

5. Conclusions

This study reveals that CDK positively and significantly impacted the parents’ reported anxiety level of their child, indicating its acceptability as a mental health support. Our qualitative and quantitative findings illustrate the role CDK can offer as a practical, viable, effective, and acceptable mental health support for children with anxiety. The program fosters increased parent–child connections as a significant outcome, facilitated by the interplay of extended time, reflexive activities, and space. In addition, over eight weeks, children are empowered through open-ended creative activities to connect to their feelings, thoughts, and imagination to build self-confidence and resilience while challenging the need for perfectionism. Comments from the parents signify that CDK creates positive mental health outcomes that last beyond the immediacy of the program.

This study adds to the small but growing evidence base supporting the role of community and cultural care in youth mental health and wellbeing. Health professionals, decision-makers and policymakers can look outside traditional care systems to improve community health and mental wellbeing. Specifically, they can look to community programs, like CDK, that emphasise self-expression, creativity, and enjoyment to nurture positivity and wellbeing. Moreover, public galleries and cultural organisations can use the findings from this study to further develop mental health and wellbeing programs as a strategic and integral part of their work. Our results support the limited positive evidence about arts engagement programs, children, and mental health, contributing to yet highlighting the need for further research in this age group.

References

- Kessler, R.C.; Petukhova, M.; Sampson, N.A.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Wittchen, H.-U. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2012, 21, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, C.; Waite, P.; Cooper, P.J. Assessment and management of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Arch. Dis. Child. 2014, 99, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertie, L.A.; Sicouri, G.; Hudson, J.L. Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents. In Comprehensive Clinical Psychology, 2nd ed.; Asmundson, G.J.G., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 217–232. [Google Scholar]

- Polanczyk, G.V.; Salum, G.A.; Sugaya, L.S.; Caye, A.; Rohde, L.A. Annual Research Review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 56, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGorry, P.D.; Mei, C. Early intervention in youth mental health: Progress and future directions. Evid.-Based Ment. Health 2018, 21, 182–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merikangas, K.R.; He, J.P.; Burstein, M.; Swendsen, J.; Avenevoli, S.; Case, B.; Georgiades, K.; Heaton, L.; Swanson, S.; Olfson, M. Service Utilization for Lifetime Mental Disorders in U.S. Adolescents: Results of the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2011, 50, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Productivity Commission. Mental Health, Report No. 95; Productivity Commission: Canberra, Australia, 2020.

- Thornicroft, G. Shunned: Discrimination Against People with Mental Illness; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Heflinger, C.A.; Hinshaw, S.P. Stigma in child and adolescent mental health services research: Understanding professional and institutional stigmatization of youth with mental health problems and their families. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2010, 37, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, S.D.; Suarez, L.; Sylvester, C. Assessment and Treatment of Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2011, 13, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, L.; Rhodes, P.; Boydell, K. Evaluation of a Gallery-Based Arts Engagement Program for Depression. Aust. Psychol. 2022, 57, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.; Knuiman, M.; Rosenberg, M. The art of being mentally healthy: A study to quantify the relationship between recreational arts engagement and mental well-being in the general population. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fancourt, D.; Finn, S. Cultural Contexts of Health: The Role of the Arts in Improving Health and Well-Being in the Who European Region, in Copenhagen; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Camic, P.M. Playing in the Mud: Health Psychology, the Arts and Creative Approaches to Health Care. J. Health Psychol. 2008, 13, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, G. Understanding the social value and well-being benefits created by museums: A case for social return on investment methodology. Arts Health 2015, 7, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, K.; McGrath, R.; Ward, E. Identifying the influence of leisure-based social circus on the health and well-being of young people in Australia. Ann. Leis. Res. 2019, 22, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romm, K.L.; Synnes, O.; Bondevik, H. Creative writing as a means to recover from early psychosis–Experiences from a group intervention. Arts Health 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bøgh, L.; Andersen, S.; Hulgaard, D.R. “Painting oneself out of a corner”–Exploring the use of art in a Child and Adolescent Psychiatry setting. Nord. J. Arts Cult. Health 2022, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mak, H.W.; Fancourt, D. Arts engagement and self-esteem in children: Results from a propensity score matching analysis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2019, 1449, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarobe, L.; Bungay, H. The role of arts activities in developing resilience and mental wellbeing in children and young people a rapid review of the literature. Perspect. Public Health 2017, 137, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, C.; Mares, S.; Robinson, G. Telling and Re-telling Stories: The Use of Narrative and Drawing in a Group Intervention with Parents and Children in a Remote Aboriginal Community. Aust. N. Z. J. Fam. Ther. 2012, 33, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassallo, S.; Swami, N. Tweens and teens: What do they worry about. In Growing up in Australia; Australian Institute of Family Studies: Melbourne, Australia, 2019; p. 133. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, D.; Gullotta, D.; Conte, I.; Boydell, K. Culture Dose for Kids: Creating an arts engagement program for young people with mild anxiety. Nord. J. Arts Cult. Health 2022, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ross, R.L.; Gullone, E.; Chorpita, B.F. The revised child anxiety and depression scale: A psychometric investigation with Australian youth. Behav. Change 2002, 19, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebesutani, C.; Reise, S.P.; Chorpita, B.F.; Ale, C.; Regan, J.; Young, J.; Higa-McMillan, C.; Weisz, J.R. The Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale-Short Version: Scale reduction via exploratory bifactor modeling of the broad anxiety factor. Psychol. Assess. 2012, 24, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, M.; Inder, M.; Porter, R. Conducting qualitative research in mental health: Thematic and content analyses. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2015, 49, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickley, T.; O’caithain, A.; Homer, C. The value of qualitative methods to public health research, policy and practice. Perspect. Public Health 2022, 142, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2014, 9, 26152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]