1. Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are chronic inflammatory diseases, mediated by the immune system, which affect the gastrointestinal tract. The two main manifestations are Crohn’s Disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). CD may affect any area of the gastrointestinal tract and has a transmural involvement. UC generally occurs only in the rectum and colon and involves the mucosa and submucosa layers [1,2].

The etiology of IBD is not completely defined. Yet, several studies support the hypothesis that their onset is due to a combination and interplay of genetic factors, immune dysregulation and environmental triggers that can modify gut microbiome [3,4,5]. In this scenario, diet is a potential environmental trigger. The global increasing incidence of IBD seems to be associated with Western lifestyle and diet: a high intake of proteins and red meat can result in an increased production of bacterial metabolites, such as an increase of ammonia, indoles, phenols, and sulphides, and a decrease of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which could all be involved in the development of IBD [6,7].

As a consequence, diet modifications have been considered therapeutic tools; for example, in pediatric IBD patients, enteral nutrition has been shown to be effective in inducing clinical remission, independently of the used formula [8,9,10].

Malnutrition, undernutrition and overnutrition seen in such patients are variable during the disease course [11] and due to suboptimal nutritional intake, alterations in nutrient requirements and metabolism, malabsorption, excessive gastrointestinal losses, and medication [12].

At the time of diagnosis, 60% of CD patients and 35% of UC patients are underweight, even if this proportion is lowered in the last years, reflecting the increased incidence of obesity [13,14]: 20–40% of adult patients with IBD are overweight (25 < body mass index (BMI) < 30 kg/m2), and an additional 15–40% are obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2) [15].

Obesity is associated with treatment failure (especially with anti-TNF drugs), risk of hospitalization, and lower endoscopic remission rates [16,17,18,19]; sarcopenia in overweight IBD patients (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) is the only significant predictor of the need for surgery (p = 0.002) [20]; nutritional deficits and low micronutrients serum levels can have a negative impact on both induction and maintenance of remission and on the quality of life of these patients [21,22]. Thus, the assessment of nutritional status in IBD patients is a crucial issue and current guidelines suggest that patients with IBD should be regularly screened for nutritional status, micronutrient deficiencies and bone mineral density [21,23].

Currently, there are limited data on the disease course and therapy response in cases of malnutrition in IBD, especially in the context of sarcopenia and undernutrition. Moreover, if micronutrient or vitamin supplementation (e.g., vitamin D supplementation) could be a potential therapeutic option or only an effect of disease activity it is still unclear [24,25].

The aim of this systematic review is trying to clarify the connection between nutrition, malnutrition (including overnutrition and undernutrition), micronutrient deficiency, and both disease course and therapeutic response in IBD patients.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was performed using PubMed/MEDLINE and Scopus. For each of the relevant publications (previous review articles and included studies), reference sections were also screened for other applicable publications.

The research strategy for each clinical question is reported in the . We found 6077 articles; 762 duplicated studies were removed. Out of 412 full texts analyzed, 227 were included in the review .

No filters were used in the search strategy. The data of the last search was May 2023. The complete selection process is reported in the .

Four authors did a systematic literature search. Clinical questions and related outcomes of interest were identified using the PICO framework. Four main clinical settings concerning adult IBD patients were identified.

- -

- Induction of remission

- -

- Maintenance of remission

- -

- Risk of surgery

- -

- Postoperative recurrence (POR) and surgery-related complications

2.1. Selection of Studies and Data Extraction

Four authors (GS, SF, SM, and MM) independently reviewed abstracts and manuscripts for eligibility.

Conflicts were resolved by consensus, referring to the original articles. The selection was made according to the following criteria:

2.2. Inclusion CriteriaPatient Type: Adult Patients (age ≥ 18) with a Confirmed Diagnosis of IBD

- -

- Intervention: Nutritional management; Nutritional evaluation; serum evaluation or supplementation of micronutrients or albumin.

- -

- Outcome: evaluation of clinical relapse or disease activity (evaluated with disease activity score or loss of response to therapy); risk of surgery; POR and surgery-related complications

- -

- Study type: Meta-analysis, Randomized clinical trial (RCT), Non-randomized study of intervention (NRSI), cross-sectional study.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

- -

- Paediatric patients

- -

- Non-human study

- -

- Lack of data concerning clinical response, risk of surgery, POR, and surgery-related complications.

Four reviewers (GS, SF, SM, and MM) independently reviewed the literature according to the above-predefined strategy and criteria and selected eligible studies; any disagreement was resolved by consensus or by recourse to a fifth author (MV).

Each reviewer extracted the data of interest in a pre-made template: title and reference details (first author, journal, year, country), study population characteristics (number of patients, gender, age, disease type (UC or CD), intervention details and outcome data (induction of remission, maintenance of remission, risk of surgery, POR, and surgery-related complications).

All data were recorded independently by the literature reviewers in separate databases and will be compared at the end of the reviewing process to limit selection bias. The database was also reviewed by another author (MV). Any disagreement was resolved by consensus or by recourse to the senior author.

3. Nutrition and Nutritional Status

If food is implicated in the pathogenesis of IBD is still not clear, but the impact of some nutrients on the behalf of the gastrointestinal tract has been suggested. For example, dietary fibre escape digestion in the small bowel and enter the colon where they are metabolized by gut bacteria which produce SCFAs, energy sources for colonocytes [26]. On the contrary red meat and other high-protein foods, contribute to sulphides formation which damages the mucus in the colon [27,28]. In the IBD population, 70% of patients report food-related symptom exacerbation, while a wide variety of foods are believed to be helpful [29]. This becomes a concern when patients drastically reduce or completely avoid important nutrients such as folic acid, calcium, vitamin B 12, and iron which represent the most frequent nutritional deficiency in IBD patients. This attitude, summed to disease duration, extent and severity, may put them at risk of developing nutritional deficiencies in the long term [30].

3.1. Nutrition and Exclusion Diet

Compared to recommended requirements, adults with IBD have an inadequate intake of energy, fibres, fat-soluble vitamins, folate and calcium [31]. Nutritional support for correcting deficiencies can be provided summarily in the form of parenteral nutrition (PN), enteral nutrition (EN) and specific diets.

3.2. Sarcopenia

Sarcopenia is defined by a loss in muscle mass and lean body mass that leads to functional changes and decreased strength [64].

The European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) developed 3 criteria for its definition and diagnosis: low muscle mass, low muscle strength, low physical performance (being necessary for the diagnosis the first criterion, plus one or both of the other two criteria) [65].

During disease flares, both the reduced caloric intake and the mucosa inflammation can impair nutrient absorption and determine weight loss [21].

3.3. Obesity

In the last decades, overweight (BMI > 25 kg/m2) and obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) increased not only in the general population but also among IBD patients [97]. In a time-trend analysis involving 10,282 CD patients (from 1991 to 2008) and including 40 RCT, the mean BMI increased from 20.8 to 27.0 [98]. Obesity and overweight were reported respectively in 18% and 38% of IBD patients, with a higher percentage of obesity in CD than in UC [99].

Only few studies analyzed the impact of obesity on the course of UC, while more data are available in CD patients. Anyhow, results are often contrasting and non-conclusive [100]. Obesity may be associated with a worse prognosis in CD in terms of perianal complications, disease activity, hospitalization, time to the first surgery and more aggressive medical treatment [101]. This could be probably due to the ability of visceral fat to produce cytokines and thus promote inflammation [102].

3.4. Albuminemia

Chronic inflammation of the mucosa determines both malabsorption and intestinal protein losses, resulting in hypoalbuminemia.

4. Anemia and Micronutrients

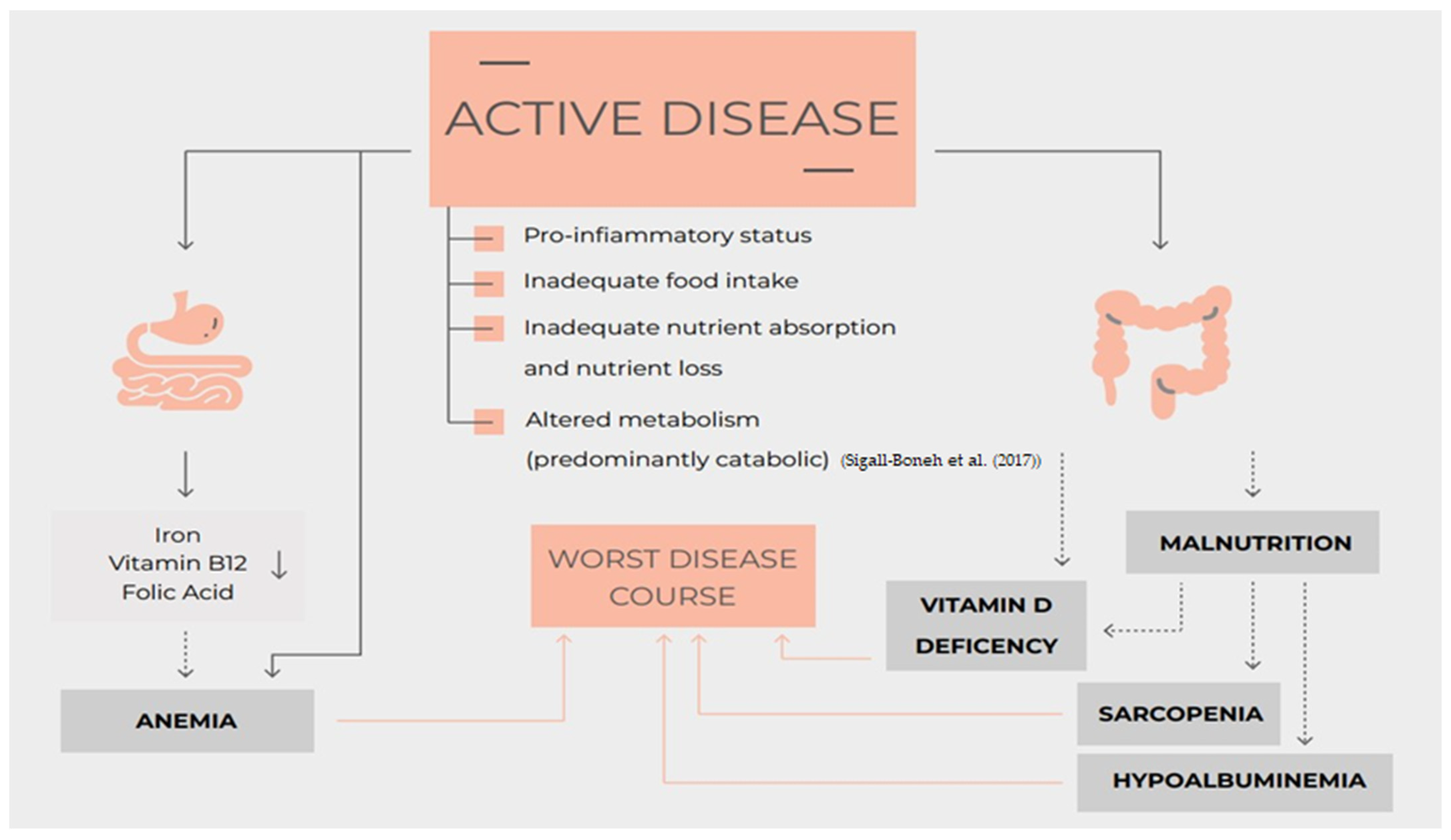

The chronic inflammatory status and the impaired absorption of nutrients due to bowel damage leads to a possible deficiency of vitamins and micronutrients that are crucial for the overall well-being [11]. If the low serum levels of these microelements are a cause or an effect of disease activity remains unclear, and if supplementation of these elements could be a potential therapeutic target is not well defined. However, the evidence is sufficiently solid in showing that active disease is linked to low serum micronutrient levels .

The micronutrients and vitamins most involved in IBD are iron, selenium, zinc, copper, manganese, vitamin D, vitamin B12 and folic acid, vitamins A, E, C, K, B1 and B6. Micronutrient and vitamin deficiencies may be linked only to IBD or also to the concomitant presence of other autoimmune diseases such as autoimmune chronic atrophic gastritis (leading to malabsorption of iron and vitamin B12) and celiac disease (responsible for malabsorption of iron and folic acid) [192].

4.1. Anemia

Anemia is a common complication of IBD. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, anemia is defined as a hemoglobin (HgB) level less than 13 g/dL in men and 12 g/dL in non-pregnant females [193].

The most common causes of anemia in IBD are iron deficiency, folic acid or vitamin B12 deficiency, chronic disease anemia due to inflammation, and combined causes. Certainly, it is crucial to classify the etiology of anemia in IBD to select the correct treatment [194,195].

Pure iron deficiency anemia is defined in the case of ferritin serum levels < 30 μg/L and the normal value of CRP; chronic disease anemia is defined by ferritin serum level > 100 μg/L and high levels of CRP. Combined anemia is defined by ferritin serum level < 100 μg/L and high levels of CRP [196].

Anemia affects the quality of life, cognitive functions, the ability to work, hospitalization, and healthcare costs [197]; if low levels of HgB could affect the disease course of IBD is not well known.

4.2. Iron

Iron deficiency (ID) is one of the worldwide most common disorders, affecting about 50% of IBD patients [195,203,204], with a prevalence ranging from 26.5% to 62.5% and representing the most common micronutrient deficiency of IBD [195,205,206,207].

In IBD patients, the diagnostic criteria for ID depend on the severity of inflammation: in remission, serum ferritin < 30 µg/L and transferrin saturation index (TSAT) < 16% are indicative of ID, while during the acute phase of the disease (CRP > 5 mg/L and/or FC > 150 mg/kg), ID is defined as ferritin < 100 µg/L.

Iron is an essential trace element involved in many cellular processes including oxygen transport, mitochondrial electron transport, gene regulation and DNA synthesis, and its deficit can manifest through a court of very heterogeneous extra-bowel symptoms including chronic fatigue, sleep disorders, agitation, decreased physical and cognitive performance, immune system impairment, significantly affecting the patient’s wellbeing [178].

Female patients and severe disease activity patients are at higher risk, due to menstrual losses in premenopausal women and to bloody diarrhoea. Interestingly, patients with ID without anaemia presented health-related quality of life (HRQoL) questionnaires with lower overall scores [178,208].

4.3. Vitamin B12 and Folic Acid

Vitamin B12 and folate deficiencies are common in patients with IBD. Folate deficiency is due to a combination of factors: poor diet, malabsorption, an increased requirement due to the increased granulocytes and other inflammatory cells, severe inflammation, resection, enteric fistulas and the use of drugs such as sulfasalazine and methotrexate [216,217].

As shown in a recent meta-analysis, the folate level in IBD patients was significantly lower compared to healthy groups; however, a lower concentration of folate was found in UC but not in CD patients [218].

Vitamin B12 deficiency is more common in CD patients compared to UC, with a prevalence of 33% and 16% respectively [219].

In CD patients, prior intestinal surgery is an independent risk factor for low serum concentrations of vitamin B12 [220]. A meta-analysis by Battat et al. identified that an ileal resection longer than 20 cm is the only factor to predispose CD patients to vitamin B12 deficiency [221].

Vitamin B12 is absorbed in the distal ileum, the intestinal tract most commonly involved in CD, and this would explain the higher prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in CD compared to UC.

A periodical assessment of blood levels of vitamins and iron is suggested. Guideline recommendations suggest checking haemoglobin and iron status every 6–12 months for patients in remission or with mild disease, and every 3 months in case of active disease. For patients at risk of vitamin B12 or folic acid deficiency (e.g., small bowel disease or resection), serum levels should be measured at least annually, or when macrocytosis is present [193].

4.4. Vitamin D

During the last few years, there has been an increase in interest concerning the immuno-modulating role of vitamin D [25,222]. Firstly, several observational and cross-sectional studies included in three meta-analyses showed that IBD patients presented low serum vitamin D levels compared to healthy people [183,223,224]. A meta-regression analysis shows that latitude does not influence the association between IBD and vitamin D deficiency (p = 0.34) [223].

4.5. Other Vitamins (A, E, K, Group B, and C)

As for other nutritional deficits, vitamin deficiency is common in IBD patients, and its pathogenesis is multifactorial [192].

A meta-analysis including 19 case-control studies, showed a lower serum level of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) in IBD patients compared to the control group.

Interestingly, in the meta-regression analysis, significant associations between vitamin A levels in CD patients, and the levels of inflammatory biomarkers (CRP: p = 0.03, and albumin p = 0.0003), were found. The data concerning vitamins E and K were not enough strong to show a correlation with disease activity, however, a clear trend was found [236]. Another study showed a lower level of vitamin K in CD. The vitamin K level (evaluated by measuring serum undercarboxylated osteocalcin) was significantly correlated with the clinical activity index among CD patients [237].

Few studies reported that vitamin C deficiency is relatively common in IBD patients, in particular in patients with reduced intake of vegetables and fruit [238,239].

Little evidence showed a plausible increase in vitamin A levels after adequate treatment for disease activity in UC patients. Plasma vitamin A is significantly lower in active UC patients compared to the control group (p = 0.0005) [240,241]. Another retrospective study including CD patients who underwent surgery showed a significantly higher basal peroxidative state and lower levels of Vitamin A and E compared to controls among the CD patients. Two months after surgery, a significant increase in serum vitamin A levels but not Vitamin E was found [242].

Concerning the other vitamin of group B only a few data are available [192,243]. However, some evidence showed that Vitamin B1 deficiency could be related to chronic fatigue in IBD patients [244].

4.6. Other Trace Elements (Selenium, Zinc, Copper, Manganese)

Zinc and Selenium are involved in the regulation of the immune response, inflammatory processes, and the regulation of oxidative stress [245,246]. Considering this, their low serum concentration may exacerbate inflammation through the dysfunction of the epithelial barrier, an altered mucosal immunity, and an increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

5. Conclusions

In a more and more ambitious approach to IBD with a treat-to-target strategy that considered tighter objectives such as mucosal healing, transmural healing, histological healing, and overall, a deep remission of the disease even the nutritional status must be considered [1,2,3,4] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Nutrition, nutritional status, micronutrients deficiency and disease course of Inflammatory Bowel Disease [11].

The evidence summarized in this review showed that many nutritional aspects could be potential targets to induce a better control of symptoms, a deeper remission, and overall improve the quality of life of IBD patients .

Certainly, many aspects summarized in this review are still lacking strong evidence. Few data are available concerning the effect of nutritional status on the induction of remission and the impact on the risk of surgery. Obviously, some clinical outcomes need data deriving from RCTs or non-randomized studies of intervention with a long follow-up (such as the risk of surgery, POR, and clinical relapse). Often these data are still lacking. Moreover, considering that the majority of available data derive from observational studies, inclusion criteria, and the analyzed outcome are often heterogeneous.

However, the large number of studies included and analyzed in this review allow us to produce a very extensive overview concerning this issue stating practical clinical aspects and highlighting the current knowledge gap helping to drive future research. An optimal nutritional status and the good management of micronutrient deficiency, ideally with the help of dietitians, may reduce this risk of clinical relapse, risk of surgery and post-operative recurrence. Considering this, all these variables should be considered for the general assessment and monitoring of IBD patients.

References

- Veauthier, B.; Hornecker, J.R. Crohn’s Disease: Diagnosis and Management. Am. Fam. Physician 2018, 98, 661–669. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, T.; Jarvis, K.; Patel, J. Diagnosis and Management of Crohn’s Disease. Am. Fam. Physician 2011, 84, 1365–1375. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, L.J.; Kabi, A.; Nickerson, K.P.; McDonald, C. Combinatorial Effects of Diet and Genetics on Inflammatory Bowel Disease Pathogenesis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 912–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, V.; Chang, E.B.; Devkota, S. Diet, Microbes, and Host Genetics: The Perfect Storm in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 48, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, E.R.; Zisman, T.; Suskind, D. The Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Current and Therapeutic Insights. J. Inflamm. Res. 2017, 10, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spooren, C.E.G.M.; Pierik, M.J.; Zeegers, M.P.; Feskens, E.J.M.; Masclee, A.A.M.; Jonkers, D.M.A.E. Review Article: The Association of Diet with Onset and Relapse in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 38, 1172–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.D. Diet, the Gut Microbiome and the Metabolome in IBD. In Nutrition, Gut Microbiota and Immunity: Therapeutic Targets for IBD: 79th Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop: New York, NY, USA, September 2013; S Karger Ag: Basel, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, E.; Gaunt, W.W.; Cardigan, T.; Garrik, V.; McGrogan, P.; Russel, R.K. The Use of Exclusive Enteral Nutrition for Induction of Remission in Children with Crohn’s Disease Demonstrates That Disease Phenotype Does Not Influence Clinical Remission. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 30, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T. Treatment of Active Crohn’s Disease in Children Using Partial Enteral Nutrition with Liquid Formula: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Gut 2006, 55, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, A.; Pigneur, B.; Garnier-Lengliné, H.; Talbotec, C.; Schmitz, J.; Canioni, D.; Goulet, O.; Ruemmele, F.M. The Efficacy of Exclusive Nutritional Therapy in Paediatric Crohn’s Disease, Comparing Fractionated Oral vs. Continuous Enteral Feeding. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 33, 1332–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigall-Boneh, R.; Levine, A.; Lomer, M.; Wierdsma, N.; Allan, P.; Fiorino, G.; Gatti, S.; Jonkers, D.; Kierkuś, J.; Katsanos, K.H.; et al. Research Gaps in Diet and Nutrition in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. A Topical Review by D-ECCO Working Group [Dietitians of ECCO]. J. Crohns Colitis 2017, 11, 1407–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimidis, K.; McGrogan, P.; Edwards, C.A. The Aetiology and Impact of Malnutrition in Paediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2011, 24, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, F.L.; Gerasimidis, K.; Papangelou, A.; Missiou, D.; Garrick, V.; Cardigan, T.; Buchanan, E.; Barclay, A.R.; McGrogan, P.; Russell, R.K. Clinical Progress in the Two Years Following a Course of Exclusive Enteral Nutrition in 109 Paediatric Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 37, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasseur, F.; Gower-Rousseau, C.; Vernier-Massouille, G.; Dupas, J.L.; Merle, V.; Merlin, B.; Lerebours, E.; Savoye, G.; Salomez, J.L.; Cortot, A.; et al. Nutritional Status and Growth in Pediatric Crohn’s Disease: A Population-Based Study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 105, 1893–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Dulai, P.S.; Zarrinpar, A.; Ramamoorthy, S.; Sandborn, W.J. Obesity in IBD: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Disease Course and Treatment Outcomes. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhalme, M.; Sharma, A.; Keld, R.; Willert, R.; Campbell, S. Does Weight-Adjusted Anti-Tumour Necrosis Factor Treatment Favour Obese Patients with Crohn’s Disease? Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 25, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, P.; Clark, T.; Dowson, G.; Warren, L.; Hamlin, J.; Hull, M.; Subramanian, V. Relationship of Body Mass Index to Clinical Outcomes after Infliximab Therapy in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. J. Crohns Colitis 2016, 10, 1144–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerbau, L.; Gerard, R.; Duveau, N.; Staumont-Sallé, D.; Branche, J.; Maunoury, V.; Cattan, S.; Wils, P.; Boualit, M.; Libier, L.; et al. Patients with Crohn’s Disease with High Body Mass Index Present More Frequent and Rapid Loss of Response to Infliximab. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 1853–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, J.W.; Sinanan, M.N.; Zisman, T.L. Increased Body Mass Index Is Associated with Earlier Time to Loss of Response to Infliximab in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 2118–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.W.; Gurwara, S.; Silver, H.J.; Horst, S.N.; Beaulieu, D.B.; Schwartz, D.A.; Seidner, D.L. Sarcopenia Is Common in Overweight Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease and May Predict Need for Surgery. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 1182–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaser, C.; Sturm, A.; Vavricka, S.R.; Kucharzik, T.; Fiorino, G.; Annese, V.; Calabrese, E.; Baumgart, D.C.; Bettenworth, D.; Borralho Nunes, P.; et al. ECCO-ESGAR Guideline for Diagnostic Assessment in IBD Part 1: Initial Diagnosis, Monitoring of Known IBD, Detection of Complications. J. Crohns Colitis 2019, 13, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubatan, J.; Moss, A.C. Vitamin D in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: More than Just a Supplement. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2018, 34, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischoff, S.C.; Barazzoni, R.; Busetto, L.; Campmans-Kuijpers, M.; Cardinale, V.; Chermesh, I.; Eshraghian, A.; Kani, H.T.; Khannoussi, W.; Lacaze, L.; et al. European Guideline on Obesity Care in Patients with Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases—Joint European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism/United European Gastroenterology Guideline. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2022, 10, 663–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valvano, M.; Magistroni, M.; Mancusi, A.; D’Ascenzo, D.; Longo, S.; Stefanelli, G.; Vernia, F.; Viscido, A.; Necozione, S.; Latella, G. The Usefulness of Serum Vitamin D Levels in the Assessment of IBD Activity and Response to Biologics. Nutrients 2021, 13, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernia, F.; Valvano, M.; Longo, S.; Cesaro, N.; Viscido, A.; Latella, G. Vitamin D in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Mechanisms of Action and Therapeutic Implications. Nutrients 2022, 14, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latella, G.; Caprilli, R. Metabolism of Large Bowel Mucosa in Health and Disease. Int. J. Color. Dis. 1991, 6, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jowett, S.L. Influence of Dietary Factors on the Clinical Course of Ulcerative Colitis: A Prospective Cohort Study. Gut 2004, 53, 1479–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasso, A.; Latella, G. Dietary Components That Counteract the Increased Risk of Colorectal Cancer Related to Red Meat Consumption. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 69, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, H.; Pedley, K.C.; Stewart, R.J.C.; Coad, J. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Are Symptoms and Diet Linked? Nutrients 2020, 12, 2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, M.; O’Morain, C. Nutrition in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2006, 20, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, K.; Pappas, D.; Miglioretto, C.; Javadpour, A.; Reveley, H.; Frank, L.; Grimm, M.C.; Samocha-Bonet, D.; Hold, G.L. Systematic Review with Meta-analysis: Dietary Intake in Adults with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 54, 742–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comeche, J.M.; Comino, I.; Altavilla, C.; Tuells, J.; Gutierrez-Hervas, A.; Caballero, P. Parenteral Nutrition in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zachos, M.; Tondeur, M.; Griffiths, A. Enteral Nutritional Therapy for Induction of Remission in Crohn’s Disease. In The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; Zachos, M., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Narula, N.; Dhillon, A.; Zhang, D.; Sherlock, M.E.; Tondeur, M.; Zachos, M. Enteral Nutritional Therapy for Induction of Remission in Crohn’s Disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 4, CD000542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messori, A.; Trallori, G.; D’albasio, G.; Milla, M.; Vannozzi, G.; Pacini, F. Defined-Formula Diets versus Steroids in the Treatment of Active Crohn’s Disease A Meta-Analysis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1996, 31, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Bañares, F.; Cabré, E.; Esteve-Comas, M.; Gassull, M.A. How Effective Is Enteral Nutrition in Inducing Clinical Remission in Active Crohn’s Disease? A Meta-Analysis of the Randomized Clinical Trials. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 1995, 19, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, A.M.; Ohlsson, A.; Sherman, P.M.; Sutherland, L.R. Meta-Analysis of Enteral Nutrition as a Primary Treatment of Active Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology 1995, 108, 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoner, P.L.; Kamel, A.; Ayoub, F.; Tan, S.; Iqbal, A.; Glover, S.C.; Zimmermann, E.M. Perioperative Care of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Focus on Nutritional Support. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2018, 2018, 7890161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.L.; Palmer, L.B.; Nguyen, E.T.; McClave, S.A.; Martindale, R.G.; Bechtold, M.L. Specialized Enteral Nutrition Therapy in Crohn’s Disease Patients on Maintenance Infliximab Therapy: A Meta-Analysis. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2015, 8, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Feng, R.; Li, T.; Xu, S.; Hao, X.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, M. Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis of Partial Enteral Nutrition for the Maintenance of Remission in Crohn’s Disease. Nutr. Res. 2020, 81, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenstein, S.; Prantera, C.; Luzi, C.; D’Ubaldi, A. Low Residue or Normal Diet in Crohn’s Disease: A Prospective Controlled Study in Italian Patients. Gut 1985, 26, 989–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, M.; Abe, T.; Tsuda, H.; Sugawara, T.; Tsuda, S.; Tozawa, H.; Fujiwara, K.; Imai, H. Lifestyle-Related Disease in Crohn’s Disease: Relapse Prevention by a Semi-Vegetarian Diet. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 2484–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, M.; Nakane, K.; Tsuji, T.; Tsuda, S.; Ishii, H.; Ohno, H.; Watanabe, K.; Obara, Y.; Komatsu, M.; Sugawara, T. Relapse Prevention by Plant-Based Diet Incorporated into Induction Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis: A Single-Group Trial. Perm. J. 2019, 23, 18–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Bañares, F.; Hinojosa, J.; Sánchez-Lombraña, J.L.; Navarro, E.; Martínez-Salmerón, J.F.; García-Pugés, A.; González-Huix, F.; Riera, J.; González-Lara, V.; Domínguez-Abascal, F.; et al. Randomized Clinical Trial of Plantago Ovata Seeds (Dietary Fiber) As Compared With Mesalamine in Maintaining Remission in Ulcerative Colitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1999, 94, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarbagili-Shabat, C.; Albenberg, L.; Van Limbergen, J.; Pressman, N.; Otley, A.; Yaakov, M.; Wine, E.; Weiner, D.; Levine, A. A Novel UC Exclusion Diet and Antibiotics for Treatment of Mild to Moderate Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis: A Prospective Open-Label Pilot Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarbagili Shabat, C.; Scaldaferri, F.; Zittan, E.; Hirsch, A.; Mentella, M.C.; Musca, T.; Cohen, N.A.; Ron, Y.; Fliss Isakov, N.; Pfeffer, J.; et al. Use of Faecal Transplantation with a Novel Diet for Mild to Moderate Active Ulcerative Colitis: The CRAFT UC Randomised Controlled Trial. J. Crohns Colitis 2022, 16, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanai, H.; Levine, A.; Hirsch, A.; Boneh, R.S.; Kopylov, U.; Eran, H.B.; Cohen, N.A.; Ron, Y.; Goren, I.; Leibovitzh, H.; et al. The Crohn’s Disease Exclusion Diet for Induction and Maintenance of Remission in Adults with Mild-to-Moderate Crohn’s Disease (CDED-AD): An Open-Label, Pilot, Randomised Trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limketkai, B.N.; Godoy-Brewer, G.; Parian, A.M.; Noorian, S.; Krishna, M.; Shah, N.D.; White, J.; Mullin, G.E. Dietary Interventions for the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 21, 2508–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J.D.; Sandler, R.S.; Brotherton, C.; Brensinger, C.; Li, H.; Kappelman, M.D.; Daniel, S.G.; Bittinger, K.; Albenberg, L.; Valentine, J.F.; et al. A Randomized Trial Comparing the Specific Carbohydrate Diet to a Mediterranean Diet in Adults With Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 837–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bemelman, W.A.; Warusavitarne, J.; Sampietro, G.M.; Serclova, Z.; Zmora, O.; Luglio, G.; de Buck van Overstraeten, A.; Burke, J.P.; Buskens, C.J.; Francesco, C.; et al. ECCO-ESCP Consensus on Surgery for Crohn’s Disease. J. Crohns Colitis 2018, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, A.; Escher, J.; Hébuterne, X.; Kłęk, S.; Krznaric, Z.; Schneider, S.; Shamir, R.; Stardelova, K.; Wierdsma, N.; Wiskin, A.E.; et al. ESPEN Guideline: Clinical Nutrition in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 321–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, G.T.; Ha, I.; Hogan, C.; Nguyen, E.; Jamal, M.M.; Bechtold, M.L.; Nguyen, D.L. Does Preoperative Enteral or Parenteral Nutrition Reduce Postoperative Complications in Crohn’s Disease Patients: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 30, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grass, F.; Pache, B.; Martin, D.; Hahnloser, D.; Demartines, N.; Hübner, M. Preoperative Nutritional Conditioning of Crohn’s Patients—Systematic Review of Current Evidence and Practice. Nutrients 2017, 9, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon-Dixon, A.; Gore-Rodney, J.; Hampal, R.; Ross, R.; Miah, A.; Amorim Adegboye, A.R.; Grimes, C.E. The Role of Exclusive Enteral Nutrition in the Pre-Operative Optimisation of Adult Patients with Crohn’s Disease. A Systematic Review. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 46, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, S.D.; Culkin, A.; Cole, J.; Clark, S.K.; Tekkis, P.P.; Ciclitira, P.J.; Nicholls, R.J.; Whelan, K. Exclusive Elemental Diet Impacts on the Gastrointestinal Microbiota and Improves Symptoms in Patients with Chronic Pouchitis. J. Crohns Colitis 2013, 7, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welters, C.F.M.; Heineman, E.; Thunnissen, F.B.J.M.; van den Bogaard, A.E.J.M.; Soeters, P.B.; Baeten, C.G.M.I. Effect of Dietary Inulin Supplementation on Inflammation of Pouch Mucosa in Patients With an Ileal Pouch-Anal Anastomosis. Dis. Colon Rectum 2002, 45, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ianco, O. Diet of Patients after Pouch Surgery May Affect Pouch Inflammation. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 6458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godny, L.; Maharshak, N.; Reshef, L.; Goren, I.; Yahav, L.; Fliss-Isakov, N.; Gophna, U.; Tulchinsky, H.; Dotan, I. Fruit Consumption Is Associated with Alterations in Microbial Composition and Lower Rates of Pouchitis. J. Crohns Colitis 2019, 13, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pironi, L.; Arends, J.; Bozzetti, F.; Cuerda, C.; Gillanders, L.; Jeppesen, P.B.; Joly, F.; Kelly, D.; Lal, S.; Staun, M.; et al. ESPEN Guidelines on Chronic Intestinal Failure in Adults. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 247–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nightingale, J. Guidelines for Management of Patients with a Short Bowel. Gut 2006, 55, iv1–iv12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, G.M.; Miller, C.; Kurian, R.; Jeejeebhoy, K.N. Diet for Patients with a Short Bowel: High Fat or High Carbohydrate? Gastroenterology 1983, 84, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordgaard, I.; Hansen, B.S.; Mortensen, P.B. Colon as a Digestive Organ in Patients with Short Bowel. Lancet 1994, 343, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, X.T.; Yang, G.; Zhuang, W.; Wei, M. Clinical Evidence of Growth Hormone, Glutamine and a Modified Diet for Short Bowel Syndrome: Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 14, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, I.H. Sarcopenia: Origins and Clinical Relevance. J. Nutr. 1997, 127, 990S–991S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Baeyens, J.P.; Bauer, J.M.; Boirie, Y.; Cederholm, T.; Landi, F.; Martin, F.C.; Michel, J.P.; Rolland, Y.; Schneider, S.M.; et al. Sarcopenia: European Consensus on Definition and Diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing 2010, 39, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Xiong, Z.; Xie, Q.; Xiao, P.; Zhang, Q.; Gu, J.; Li, J.; Hu, D.; Hu, X.; Shen, Y.; et al. Computed Tomography-Based Multiple Body Composition Parameters Predict Outcomes in Crohn’s Disease. Insights Imaging 2021, 12, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cravo, M.L.; Velho, S.; Torres, J.; Costa Santos, M.P.; Palmela, C.; Cruz, R.; Strecht, J.; Maio, R.; Baracos, V. Lower Skeletal Muscle Attenuation and High Visceral Fat Index Are Associated with Complicated Disease in Patients with Crohn’s Disease: An Exploratory Study. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2017, 21, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labarthe, G.; Dolores, M.; Verdalle-Cazes, M.; Charpentier, C.; Roullee, P.; Dacher, J.N.; Savoye, G.; Savoye-Collet, C. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Assessment of Body Composition Parameters in Crohn’s Disease. Dig. Liver Dis. 2020, 52, 878–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, S.M.; Al-Jaouni, R.; Filippi, J.; Wiroth, J.B.; Zeanandin, G.; Arab, K.; Hébuterne, X. Sarcopenia Is Prevalent in Patients with Crohn’s Disease in Clinical Remission. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2008, 14, 1562–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, D.Q.; Moore, G.T.; Strauss, B.J.G.; Hamilton, A.L.; De Cruz, P.; Kamm, M.A. Visceral Adiposity Predicts Post-Operative Crohn’s Disease Recurrence. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 45, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Yoon, H.; Oh, D.J.; Lee, J.M.; Choi, Y.J.; Shin, C.M.; Park, Y.S.; Kim, N.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, J.S. The Prevalence of Sarcopenia and Its Effect on Prognosis in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Intest. Res. 2020, 18, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yu, D.; Hong, L.; Zhang, T.; Liu, H.; Fan, R.; Wang, L.; Zhong, J.; Wang, Z. Prevalence of Sarcopenia and Its Effect on Postoperative Complications in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2021, 2021, 3267201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grova, M.; Crispino, F.; Maida, M.; Renna, S.; Casà, A.; Tesè, L.; Macaluso, F.S.; Orlando, A. Sarcopenia Is a Poor Prognostic Factor for Endoscopic Remission in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. In Proceedings of the XIII Congresso Nazionale IG-IBD, Riccione, Italy, 1–3 December 2022; pp. S84–S85. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.T.; James, S.; Tran, A.; Kutaiba, N. Sarcopenia Measurements and Clinical Outcomes in Crohn’s Disease Surgical Patients. ANZ J. Surg. 2022, 92, 3209–3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boparai, G.; Kedia, S.; Kandasamy, D.; Sharma, R.; Madhusudhan, K.S.; Dash, N.R.; Sahu, P.; Pal, S.; Sahni, P.; Panwar, R.; et al. Combination of Sarcopenia and High Visceral Fat Predict Poor Outcomes in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 75, 1491–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erős, A.; Soós, A.; Hegyi, P.; Szakács, Z.; Benke, M.; Szűcs, Á.; Hartmann, P.; Erőss, B.; Sarlós, P. Sarcopenia as an Independent Predictor of the Surgical Outcomes of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Surg. Today 2020, 50, 1138–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Ding, X.; Maggiore, G.; Pietrobattista, A.; Satapathy, S.K.; Tian, Z.; Jing, X. Sarcopenia Is Associated with Poor Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, J.P.; Teigen, L.; Manski, S.; Blumhof, B.; Guglielmo, F.F.; Shivashankar, R.; Shmidt, E. Sarcopenia Is More Prevalent Among Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients Undergoing Surgery and Predicts Progression to Surgery Among Medically Treated Patients. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2022, 28, 1844–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grillot, J.; D’Engremont, C.; Parmentier, A.L.; Lakkis, Z.; Piton, G.; Cazaux, D.; Gay, C.; De Billy, M.; Koch, S.; Borot, S.; et al. Sarcopenia and Visceral Obesity Assessed by Computed Tomography Are Associated with Adverse Outcomes in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 3024–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamba, S.; Sasaki, M.; Takaoka, A.; Takahashi, K.; Imaeda, H.; Nishida, A.; Inatomi, O.; Sugimoto, M.; Andoh, A. Sarcopenia Is a Predictive Factor for Intestinal Resection in Admitted Patients with Crohn’s Disease. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spooren, C.E.G.M.; Lodewick, T.M.; Beelen, E.M.J.; Dijk, D.P.J.; Bours, M.J.L.; Haans, J.J.; Masclee, A.A.M.; Pierik, M.J.; Bakers, F.C.H.; Jonkers, D.M.A.E. The Reproducibility of Skeletal Muscle Signal Intensity on Routine Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Crohn’s Disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 35, 1902–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardone, O.M.; Ponsiglione, A.; de Sire, R.; Calabrese, G.; Liuzzi, R.; Testa, A.; Guarino, A.D.; Olmo, O.; Rispo, A.; Camera, L.; et al. Impact of Sarcopenia on Clinical Outcomes in a Cohort of Caucasian Active Crohn’s Disease Patients Undergoing Multidetector CT-Enterography. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiberge, C.; Charpentier, C.; Gillibert, A.; Modzelewski, R.; Dacher, J.N.; Savoye, G.; Savoye-Collet, C. Lower Subcutaneous or Visceral Adiposity Assessed by Abdominal Computed Tomography Could Predict Adverse Outcome in Patients With Crohn’s Disease. J. Crohns Colitis 2018, 12, 1429–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D.; Viana, C.; Marques, I.; Costa, C.; Martins, S.F. Sarcopenia Is Associated with Postoperative Outcome in Patients with Crohn’s Disease Undergoing Bowel Resection. Gastrointest. Disord. 2019, 1, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Xia, J.; Wu, Y.; Ye, L.; Liu, W.; Qi, W.; Cao, Q.; Bai, R.; Zhou, W. Sarcopenia Assessed by Computed Tomography Is Associated with Colectomy in Patients with Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 76, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cushing, K.C.; Kordbacheh, H.; Gee, M.S.; Kambadakone, A.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N. Sarcopenia Is a Novel Predictor of the Need for Rescue Therapy in Hospitalized Ulcerative Colitis Patients. J. Crohns Colitis 2018, 12, 1036–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, X.; Jiang, L.; Yu, W.; Wu, Y.; Liu, W.; Qi, W.; Cao, Q.; Bai, R.; Zhou, W. The Importance of Sarcopenia as a Prognostic Predictor of the Clinical Course in Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis Patients. Dig. Liver Dis. 2021, 53, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, M.; Yamada, A.; Komaki, Y.; Komaki, F.; Cohen, R.D.; Dalal, S.; Hurst, R.D.; Hyman, N.; Pekow, J.; Shogan, B.D.; et al. Low Skeletal Muscle Index Adjusted for Body Mass Index Is an Independent Risk Factor for Inflammatory Bowel Disease Surgical Complications. Crohns Colitis 360 2020, 2, otaa064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, M.; Cromwell, J.; Nau, P. Sarcopenia Is a Predictor of Surgical Morbidity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 1867–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinder, M.W.; Clifford, M.; Jones, A.L.; Shepherd, T.; Jacob, A.O. The Impact of Sarcopenia on Outcomes in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Undergoing Colorectal Surgery. ANZ J. Surg. 2022, 92, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alipour, O.; Lee, V.; Tejura, T.K.; Wilson, M.L.; Memel, Z.; Cho, J.; Cologne, K.; Hwang, C.; Shao, L. The Assessment of Sarcopenia Using Psoas Muscle Thickness per Height Is Not Predictive of Post-Operative Complications in IBD. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 56, 1175–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Cao, L.; Cao, T.; Yang, J.; Gong, J.; Zhu, W.; Li, N.; Li, J. Prevalence of Sarcopenia and Its Impact on Postoperative Outcome in Patients with Crohn’s Disease Undergoing Bowel Resection. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2017, 41, 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zager, Y.; Khalilieh, S.; Ganaiem, O.; Gorgov, E.; Horesh, N.; Anteby, R.; Kopylov, U.; Jacoby, H.; Dreznik, Y.; Dori, A.; et al. Low Psoas Muscle Area Is Associated with Postoperative Complications in Crohn’s Disease. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2021, 36, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galata, C.; Hodapp, J.; Weiß, C.; Karampinis, I.; Vassilev, G.; Reißfelder, C.; Otto, M. Skeletal Muscle Mass Index Predicts Postoperative Complications in Intestinal Surgery for Crohn’s Disease. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2020, 44, 714–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celentano, V.; Kamil-Mustafa, L.; Beable, R.; Ball, C.; Flashman, K.G.; Jennings, Z.; O’ Leary, D.P.; Higginson, A.; Luxton, S. Preoperative Assessment of Skeletal Muscle Mass during Magnetic Resonance Enterography in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Updat. Surg. 2021, 73, 1419–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujikawa, H.; Araki, T.; Okita, Y.; Kondo, S.; Kawamura, M.; Hiro, J.; Toiyama, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Tanaka, K.; Inoue, Y.; et al. Impact of Sarcopenia on Surgical Site Infection after Restorative Proctocolectomy for Ulcerative Colitis. Surg. Today 2017, 47, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, J.W.; Zisman, T.L. Interaction of Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 7868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, G.W.; Dubeau, M.F.; Kaplan, G.G.; Panaccione, R.; Ghosh, S. The Increasing Weight of Crohn’s Disease Subjects in Clinical Trials. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 2949–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutros, M.; Maron, D. Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the Obese Patient. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 2011, 24, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.; Loftus, E. Obesity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Review of Its Role in the Pathogenesis, Natural History, and Treatment of IBD. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connelly, T.M.; Juza, R.M.; Sangster, W.; Sehgal, R.; Tappouni, R.F.; Messaris, E. Volumetric Fat Ratio and Not Body Mass Index Is Predictive of Ileocolectomy Outcomes in Crohn’s Disease Patients. Dig. Surg. 2014, 31, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, P.; Magro, F.; Martel, F. Metabolic Inflammation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, S.M.; Harper, J.; Zisman, T.L. Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2018, 34, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seminerio, J.L.; Koutroubakis, I.E.; Ramos-Rivers, C.; Hashash, J.G.; Dudekula, A.; Regueiro, M.; Baidoo, L.; Barrie, A.; Swoger, J.; Schwartz, M.; et al. Impact of Obesity on the Management and Clinical Course of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 2857–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juillerat, P.; Sokol, H.; Froehlich, F.; Yajnik, V.; Beaugerie, L.; Lucci, M.; Burnand, B.; Macpherson, A.J.; Cosnes, J.; Korzenik, J.R. Factors Associated with Durable Response to Infliximab in Crohn’s Disease 5 Years and Beyond. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Proudfoot, J.; Xu, R.; Sandborn, W.J. Obesity and Response to Infliximab in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Pooled Analysis of Individual Participant Data from Clinical Trials. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 113, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowan, C.R.; McManus, J.; Boland, K.; O’Toole, A. Visceral Adiposity and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2021, 36, 2305–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Ren, J.; Li, G.; Wu, X.; Li, J. The Impact of Obesity on the Clinical Course of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Med. Sci. Monit. 2017, 23, 2599–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pringle, P.L.; Stewart, K.O.; Peloquin, J.M.; Sturgeon, H.C.; Nguyen, D.; Sauk, J.; Garber, J.J.; Yajnik, V.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Chan, A.T.; et al. Body Mass Index, Genetic Susceptibility, and Risk of Complications Among Individuals with Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 2304–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hass, D.; Brensinger, C.; LEWIS, J.; Lichtenstein, G. The Impact of Increased Body Mass Index on the Clinical Course of Crohn’s Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 4, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Sloot, K.W.J.; Joshi, A.D.; Bellavance, D.R.; Gilpin, K.K.; Stewart, K.O.; Lochhead, P.; Garber, J.J.; Giallourakis, C.; Yajnik, V.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; et al. Visceral Adiposity, Genetic Susceptibility, and Risk of Complications Among Individuals with Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Chen, B.; Lou, D.; Zhang, M.; Shi, Y.; Dai, W.; Shen, J.; Zhou, B.; Hu, J. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Association between Obesity/Overweight and Surgical Complications in IBD. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2022, 37, 1485–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, G.; Abdulaal, A.; Slesser, A.A.P.; Mohsen, Y. Outcomes of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Surgery in Obese versus Non-Obese Patients: A Meta-Analysis. Tech. Coloproctology 2019, 23, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emile, S.H.; Khan, S.M.; Wexner, S.D. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Outcome of Ileal Pouch Anal Anastomosis in Patients with Obesity. Surgery 2021, 170, 1629–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causey, M.W.; Johnson, E.K.; Miller, S.; Martin, M.; Maykel, J.; Steele, S.R. The Impact of Obesity on Outcomes Following Major Surgery for Crohn’s Disease: An American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Assessment. Dis. Colon Rectum 2011, 54, 1488–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.H.; Yu, G.Y.; Khan, F.; Li, J.Q.; Stocchi, L.; Hull, T.L.; Shen, B. Greater Peripouch Fat Area on CT Image Is Associated with Chronic Pouchitis and Pouch Failure in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Patients. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2020, 65, 3660–3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zhu, F.; Gong, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, T.; Gu, L.; Zhu, W.; Guo, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, N.; et al. High Visceral to Subcutaneous Fat Ratio Is Associated with Increased Postoperative Inflammatory Response after Colorectal Resection in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2018, 2018, 6270514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenefuss, F.; Hoffmann, P. Serum γ-Globulin and Albumin Concentrations Predict Secondary Loss of Response to Anti-TNFα in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 31, 1563–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tighe, D.; Hall, B.; Jeyarajah, S.K.; Smith, S.; Breslin, N.; Ryan, B.; McNamara, D. One-Year Clinical Outcomes in an IBD Cohort Who Have Previously Had Anti-TNFa Trough and Antibody Levels Assessed. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 1154–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotan, I.; Ron, Y.; Yanai, H.; Becker, S.; Fishman, S.; Yahav, L.; Ben Yehoyada, M.; Mould, D.R. Patient Factors That Increase Infliximab Clearance and Shorten Half-Life in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 2247–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berends, S.E.; Strik, A.S.; Jansen, J.M.; de Boer, N.K.; van Egmond, P.S.; Brandse, J.F.; Mathôt, R.A.; D’Haens, G.R.; Löwenberg, M. Pharmacokinetics of Golimumab in Moderate to Severe Ulcerative Colitis: The GO-KINETIC Study. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 54, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Varma, S.; Freedberg, D.E.; Axelrad, J.E. A Simple Emergency Department-Based Score Predicts Complex Hospitalization in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2022, 67, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Matsui, T.; Ito, H.; Ashida, T.; Nakamura, S.; Motoya, S.; Matsumoto, T.; Sato, N.; Ozaki, K.; Watanabe, M.; et al. Circulating Interleukin 6 and Albumin, and Infliximab Levels Are Good Predictors of Recovering Efficacy After Dose Escalation Infliximab Therapy in Patients with Loss of Response to Treatment for Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 2114–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhardt, H.J.; Loeschke, K.; Kasper, H.; Holtermüller, K.H.; Schäfer, H. European Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study (ECCDS): Clinical Features and Natural History. Digestion 1985, 31, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaly, S.; Murray, K.; Baird, A.; Martin, K.; Prosser, R.; Mill, J.; Simms, L.A.; Hart, P.H.; Radford-Smith, G.; Bampton, P.A.; et al. High Vitamin D-Binding Protein Concentration, Low Albumin, and Mode of Remission Predict Relapse in Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 2456–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroi, R.; Endo, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Naito, T.; Onodera, M.; Kuroha, M.; Kanazawa, Y.; Kimura, T.; Kakuta, Y.; Masamune, A.; et al. Long-Term Prognosis of Japanese Patients with Biologic-Naïve Crohn’s Disease Treated with Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Antibodies. Intest. Res. 2019, 17, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaeda, H.; Takahashi, K.; Fujimoto, T.; Bamba, S.; Tsujikawa, T.; Sasaki, M.; Fujiyama, Y.; Andoh, A. Clinical Utility of Newly Developed Immunoassays for Serum Concentrations of Adalimumab and Anti-Adalimumab Antibodies in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 49, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, P.; Ansari, N.; Young, C.J.; Solomon, M.J. Definitive Surgical Closure of Enterocutaneous Fistula: Outcome and Factors Predictive of Increased Postoperative Morbidity. Color. Dis. 2014, 16, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneno, K.; Hisamatsu, T.; Matsuoka, K.; Okamoto, S.; Takayama, T.; Ichikawa, R.; Sujino, T.; Miyoshi, J.; Takabayashi, K.; Mikami, Y.; et al. Risk and Management of Intra-Abdominal Abscess in Crohn’s Disease Treated with Infliximab. Digestion 2014, 89, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lok, K.H.; Ng, C.H.; Hung, H.G.; Li, K.F.; Li, K.K.; Szeto, M.L. Correlation of Serum Biomarkers with Clinical Severity and Mucosal Inflammation in Chinese Ulcerative Colitis Patients. J. Dig. Dis. 2008, 9, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Patel, D.; Shah, Y.; Trivedi, C.; Yang, Y.X. Albumin as a Prognostic Marker for Ulcerative Colitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 8008–8016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Walshe, M.; Oh, E.H.; Hwang, S.W.; Park, S.H.; Yang, D.H.; Byeon, J.S.; Myung, S.J.; Yang, S.K.; Greener, T.; et al. Early Changes in Serum Albumin Predict Clinical and Endoscopic Outcomes in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis Starting Anti-TNF Treatment. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2021, 27, 1452–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langholz, E.; Munkholm, P.; Davidsen, M.; Nielsen, O.H.; Binder, V. Changes in Extent of Ulcerative Colitis A Study on the Course and Prognostic Factors. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1996, 31, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Ghoshal, U.C.; Aggarwal, R.; Saraswat, V.A.; Choudhuri, G. Severe Ulcerative Colitis: Prospective Study of Parameters Determining Outcome. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Aust. 2004, 19, 1247–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, M.T.; Vande Casteele, N.; Vermeire, S.; de Buck van Overstraeten, A.; Billiet, T.; Baert, F.; Wolthuis, A.; Van Assche, G.; Noman, M.; Hoffman, I.; et al. A Panel to Predict Long-Term Outcome of Infliximab Therapy for Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 13, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Baut, G.; Kirchgesner, J.; Amiot, A.; Lefevre, J.H.; Chafai, N.; Landman, C.; Nion, I.; Bourrier, A.; Delattre, C.; Martineau, C.; et al. A Scoring System to Determine Patients’ Risk of Colectomy Within 1 Year After Hospital Admission for Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 1602–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Takagi, T.; Naito, Y.; Uchiyama, K.; Hotta, Y.; Toyokawa, Y.; Kashiwagi, S.; Kamada, K.; Ishikawa, T.; Yasuda, H.; et al. Low Serum Albumin at Admission Is a Predictor of Early Colectomy in Patients with Moderate to Severe Ulcerative Colitis. JGH Open 2021, 5, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Con, D.; Andrew, B.; Nicolaides, S.; van Langenberg, D.R.; Vasudevan, A. Biomarker Dynamics during Infliximab Salvage for Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis: C-Reactive Protein (CRP)-Lymphocyte Ratio and CRP-Albumin Ratio Are Useful in Predicting Colectomy. Intest. Res. 2022, 20, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, D.J.; Hartery, K.; Doherty, J.; Nolan, J.; Keegan, D.; Byrne, K.; Martin, S.T.; Buckley, M.; Sheridan, J.; Horgan, G.; et al. CRP/Albumin Ratio: An Early Predictor of Steroid Responsiveness in Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2018, 52, e48–e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choy, M.C.; Seah, D.; Gorelik, A.; An, Y.K.; Chen, C.Y.; Macrae, F.A.; Sparrow, M.P.; Connell, W.R.; Moore, G.T.; Radford-Smith, G.; et al. Predicting Response after Infliximab Salvage in Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 33, 1347–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stidham, R.W.; Guentner, A.S.; Ruma, J.L.; Govani, S.M.; Waljee, A.K.; Higgins, P.D.R. Intestinal Dilation and Platelet:Albumin Ratio Are Predictors of Surgery in Stricturing Small Bowel Crohn’s Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 1112–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syal, G.; Robbins, L.; Kashani, A.; Bonthala, N.; Feldman, E.; Fleshner, P.; Vasiliauskas, E.; McGovern, D.; Ha, C.; Targan, S.; et al. Hypoalbuminemia and Bandemia Predict Failure of Infliximab Rescue Therapy in Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2021, 66, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, N.; Miyazu, T.; Tamura, S.; Tani, S.; Yamade, M.; Iwaizumi, M.; Hamaya, Y.; Osawa, S.; Furuta, T.; Sugimoto, K. Early Serum Albumin Changes in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis Treated with Tacrolimus Will Predict Clinical Outcome. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 3109–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, N.; Tani, S.; Asai, Y.; Miyazu, T.; Tamura, S.; Yamade, M.; Iwaizumi, M.; Hamaya, Y.; Osawa, S.; Furuta, T.; et al. Lymphocyte to Monocyte Ratio and Serum Albumin Changes Predict Tacrolimus Therapy Outcomes in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Shimoyama, T.; Umegae, S.; Kotze, P.G. Impact of Preoperative Nutritional Status on the Incidence Rate of Surgical Complications in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease With Vs Without Preoperative Biologic Therapy: A Case-Control Study. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2019, 10, e00050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.K.; Tapping, C.R.; Foley, G.T.; Baker, R.P.; Sagar, P.M.; Burke, D.A.; Sue-Ling, H.M.; Finan, P.J. Morbidity and Mortality after Closure of Loop Ileostomy. Color. Dis. 2009, 11, 866–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telem, D.A. Risk Factors for Anastomotic Leak Following Colorectal Surgery. Arch. Surg. 2010, 145, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Ge, X.; Yang, J.; Zhang, T.; Xie, T.; Gao, W.; Gong, J.; Zhu, W. Increased Incidence of Prolonged Ileus after Colectomy for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases under ERAS Protocol: A Cohort Analysis. J. Surg. Res. 2017, 212, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimann, T.M.; Swaminathan, S.; Greenstein, A.J.; Steinhagen, R.M. Incidence and Factors Correlating With Incisional Hernia Following Open Bowel Resection in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Ann. Surg. 2018, 267, 532–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almogy, G.; Bodian, C.A.; Greenstein, A.J. Surgery for Late-Onset Ulcerative Colitis: Predictors of Short-Term Outcome. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2002, 37, 1025–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Stocchi, L.; Remzi, F.; Kiran, R.P. Factors Associated with Postoperative Morbidity, Reoperation and Readmission Rates after Laparoscopic Total Abdominal Colectomy for Ulcerative Colitis. Color. Dis. 2013, 15, 1123–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Stocchi, L.; Gorgun, E.; Remzi, F.H. Risk Factors Associated with Portomesenteric Venous Thrombosis in Patients Undergoing Restorative Proctocolectomy for Medically Refractory Ulcerative Colitis. Color. Dis. 2016, 18, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, P.J.; Appau, K.A.; Remzi, F.H.; Kiran, R.P. Preoperative Hypoalbuminemia Is Associated with Adverse Outcomes after Ileoanal Pouch Surgery. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2012, 18, 1034–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lyu, H.; Yang, H.; Li, Y.; Tan, B.; Wei, M.M.; Sun, X.Y.; Li, J.N.; Wu, B.; Qian, J.M. Preoperative Corticosteroid Usage and Hypoalbuminemia Increase Occurrence of Short-Term Postoperative Complications in Chinese Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Chin. Med. J. 2016, 129, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofo, L.; Caprino, P.; Schena, C.A.; Sacchetti, F.; Potenza, A.E.; Ciociola, A. New Perspectives in the Prediction of Postoperative Complications for High-Risk Ulcerative Colitis Patients: Machine Learning Preliminary Approach. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 12781–12787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hussuna, A.; Iesalnieks, I.; Horesh, N.; Hadi, S.; Dreznik, Y.; Zmora, O. The Effect of Pre-Operative Optimization on Post-Operative Outcome in Crohn’s Disease Resections. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2017, 32, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galata, C.; Kienle, P.; Weiss, C.; Seyfried, S.; Reißfelder, C.; Hardt, J. Risk Factors for Early Postoperative Complications in Patients with Crohn’s Disease after Colorectal Surgery Other than Ileocecal Resection or Right Hemicolectomy. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2019, 34, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riss, S.; Bittermann, C.; Zandl, S.; Kristo, I.; Stift, A.; Papay, P.; Vogelsang, H.; Mittlböck, M.; Herbst, F. Short-Term Complications of Wide-Lumen Stapled Anastomosis after Ileocolic Resection for Crohn’s Disease: Who Is at Risk? Color. Dis. 2010, 12, e298–e303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchetti, F.; Caprino, P.; Potenza, A.E.; Pastena, D.; Presacco, S.; Sofo, L. Early and Late Outcomes of a Series of 255 Patients with Crohn’s Disease Who Underwent Resection: 10 Years of Experience at a Single Referral Center. Updat. Surg. 2022, 74, 1657–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoneima, A.S.; Flashman, K.; Dawe, V.; Baldwin, E.; Celentano, V. High Risk of Septic Complications Following Surgery for Crohn’s Disease in Patients with Preoperative Anaemia, Hypoalbuminemia and High CRP. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2019, 34, 2185–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, X.; Zhou, C.; Hu, T.; Ke, J.; Chen, Y.; He, X.; Zheng, X.; He, X.; Hu, J.; et al. Preoperative Hypoalbuminemia Is Associated with an Increased Risk for Intra-Abdominal Septic Complications after Primary Anastomosis for Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2017, 5, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morar, P.S.; Hodgkinson, J.D.; Thalayasingam, S.; Koysombat, K.; Purcell, M.; Hart, A.L.; Warusavitarne, J.; Faiz, O. Determining Predictors for Intra-Abdominal Septic Complications Following Ileocolonic Resection for Crohn’s Disease--Considerations in Pre-Operative and Peri-Operative Optimisation Techniques to Improve Outcome. J. Crohns Colitis 2015, 9, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yang, J.; Ding, C.; Li, Y.; Gu, L.; Wei, Y.; Cao, L.; Gong, J.; Zhu, W.; Li, N.; et al. Preoperative Intra-Abdominal Sepsis, Not Penetrating Behavior Itself, Is Associated With Worse Postoperative Outcome After Bowel Resection for Crohn Disease. Medicine 2015, 94, e1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z.; Cao, L.; Feng, D.; Zhang, T.; Zhu, W.; Gong, J. Nomogram to Predict Postoperative Intra-Abdominal Septic Complications After Bowel Resection and Primary Anastomosis for Crohn’s Disease. Dis. Colon Rectum 2020, 63, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, C.; Stift, A.; Argeny, S.; Bergmann, M.; Gnant, M.; Marolt, S.; Unger, L.; Riss, S. Delta Albumin Is a Better Prognostic Marker for Complications Following Laparoscopic Intestinal Resection for Crohn’s Disease than Albumin Alone—A Retrospective Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Hussuna, A.; Karer, M.L.M.; Uldall Nielsen, N.N.; Mujukian, A.; Fleshner, P.R.; Iesalnieks, I.; Horesh, N.; Kopylov, U.; Jacoby, H.; Al-Qaisi, H.M.; et al. Postoperative Complications and Waiting Time for Surgical Intervention after Radiologically Guided Drainage of Intra-Abdominal Abscess in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. BJS Open 2021, 5, zrab075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiraoka, S.; Takashima, S.; Kondo, Y.; Inokuchi, T.; Sugihara, Y.; Takahara, M.; Kawano, S.; Harada, K.; Kato, J.; Okada, H. Efficacy of Restarting Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor α Agents after Surgery in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Intest. Res. 2018, 16, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; McGinley, E.L.; Binion, D.G.; Saeian, K. A Novel Risk Score to Stratify Severity of Crohn’s Disease Hospitalizations. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 105, 1799–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vohra, I.; Attar, B.; Haghbin, H.; Mutneja, H.; Katiyar, V.; Sharma, S.; Abegunde, A.T.; Demetria, M.; Gandhi, S. Incidence and Risk Factors for 30-Day Readmission in Ulcerative Colitis: Nationwide Analysis in Biologic Era. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 33, 1174–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Jung, E.S.; Lee, J.H.; Hong, S.P.; Kim, T.I.; Kim, W.H.; Cheon, J.H. Long-Term Clinical Outcomes and Factors Predictive of Relapse after 5-Aminosalicylate or Sulfasalazine Therapy in Patients with Mild-to-Moderate Ulcerative Colitis. Hepato-Gastroenterology 2012, 59, 1415–1420. [Google Scholar]

- Abou Khalil, M.; Boutros, M.; Nedjar, H.; Morin, N.; Ghitulescu, G.; Vasilevsky, C.A.; Gordon, P.; Rahme, E. Incidence Rates and Predictors of Colectomy for Ulcerative Colitis in the Era of Biologics: Results from a Provincial Database. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2018, 22, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydinli, H.H.; Aytac, E.; Remzi, F.H.; Bernstein, M.; Grucela, A.L. Factors Associated with Short-Term Morbidity in Patients Undergoing Colon Resection for Crohn’s Disease. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2018, 22, 1434–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, K.; Varma, D.; Mahadevan, P.; Narayanan, R.G.; Philip, M. Surgical Treatment for Small Bowel Crohn’s Disease: An Experience of 28 Cases. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 27, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Iesalnieks, I.; Spinelli, A.; Frasson, M.; Di Candido, F.; Scheef, B.; Horesh, N.; Iborra, M.; Schlitt, H.J.; El-Hussuna, A. Risk of Postoperative Morbidity in Patients Having Bowel Resection for Colonic Crohn’s Disease. Tech. Coloproctol. 2018, 22, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Wu, X.; Hu, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhou, C.; He, X.; Zhi, M.; Wu, X.; Lan, P. Incidence and Risk Factors for Incisional Surgical Site Infection in Patients with Crohn’s Disease Undergoing Bowel Resection. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2018, 6, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, D.W.; Abd El Aziz, M.A.; Perry, W.; Behm, K.T.; Shawki, S.; Mandrekar, J.; Mathis, K.L.; Grass, F. Surgical Resection for Crohn’s and Cancer: A Comparison of Disease-Specific Risk Factors and Outcomes. Dig. Surg. 2021, 38, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozios, I.; Seeliger, H.; Lauscher, J.C.; Stroux, A.; Weixler, B.; Kamphues, C.; Beyer, K.; Kreis, M.E.; Lehmann, K.S.; Seifarth, C. Risk Factors for Upper and Lower Type Prolonged Postoperative Ileus Following Surgery for Crohn’s Disease. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2021, 36, 2165–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-deGuise, C.; Casellas, F.; Robles, V.; Navarro, E.; Borruel, N. Iron Deficiency in the Absence of Anemia Impairs the Perception of Health-Related Quality of Life of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 1450–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Lopez, A.; Cummings, J.R.F.; Dignass, A.; Detlie, T.E.; Danese, S. Review Article: Treating-to-Target for Inflammatory Bowel Disease-Associated Anaemia. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 48, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, M.; Deloughery, T. Single-Dose Intravenous Iron for Iron Deficiency: A New Paradigm. Hematology 2016, 2016, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çekiç, C.; İpek, S.; Aslan, F.; Akpınar, Z.; Arabul, M.; Topal, F.; Sarıtaş Yüksel, E.; Alper, E.; Ünsal, B. The Effect of Intravenous Iron Treatment on Quality of Life in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients with Nonanemic Iron Deficiency. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2015, 2015, 582163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huguet, J.M.; Cortés, X.; Boscá-Watts, M.M.; Muñoz, M.; Maroto, N.; Iborra, M.; Hinojosa, E.; Capilla, M.; Asencio, C.; Amoros, C.; et al. Ferric Carboxymaltose Improves the Quality of Life of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Iron Deficiency without Anaemia. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghian, M.; Saneei, P.; Siassi, F.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Vitamin D Status in Relation to Crohn’s Disease: Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrition 2016, 32, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubatan, J.; Chou, N.D.; Nielsen, O.H.; Moss, A.C. Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis: Association of Vitamin D Status with Clinical Outcomes in Adult Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 50, 1146–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruyn, J.R.; Bossuyt, P.; Ferrante, M.; West, R.L.; Dijkstra, G.; Witteman, B.J.; Wildenberg, M.; Hoentjen, F.; Franchimont, D.; Clasquin, E.; et al. High-Dose Vitamin D Does Not Prevent Postoperative Recurrence of Crohn’s Disease in a Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 1573–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valvano, M.; Magistroni, M.; Cesaro, N.; Carlino, G.; Monaco, S.; Fabiani, S.; Vinci, A.; Vernia, F.; Viscido, A.; Latella, G. Effectiveness of Vitamin D Supplementation on Disease Course in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients: Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2022, izac253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.P.; Mee, A.S.; Parfitt, A.; Marks, I.N.; Burns, D.G.; Sherman, M.; Tigler-Wybrandi, N.; Isaacs, S. Vitamin A Therapy in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology 1985, 88, 512–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bager, P.; Hvas, C.L.; Rud, C.L.; Dahlerup, J.F. Randomised Clinical Trial: High-Dose Oral Thiamine versus Placebo for Chronic Fatigue in Patients with Quiescent Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 53, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Von Martels, J.Z.H.; Bourgonje, A.R.; Klaassen, M.A.Y.; Alkhalifah, H.A.A.; Sadaghian Sadabad, M.; Vich Vila, A.; Gacesa, R.; Gabriëls, R.Y.; Steinert, R.E.; Jansen, B.H.; et al. Riboflavin Supplementation in Patients with Crohn’s Disease [the RISE-UP Study]. J. Crohns Colitis 2020, 14, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itagaki, M.; Saruta, M.; Saijo, H.; Mitobe, J.; Arihiro, S.; Matsuoka, M.; Kato, T.; Ikegami, M.; Tajiri, H. Efficacy of Zinc–Carnosine Chelate Compound, Polaprezinc, Enemas in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 49, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedman, J.D.; Spyrou, N.M.; Millar, A.D.; Altaf, W.J.; Akanle, O.A.; Rampton, D.S. Selenium Supplementation in the Diets of Patients Suffering from Ulcerative Colitis. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 1997, 217, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, C.; Dong, W. Adjunctive Therapeutic Effects of Micronutrient Supplementation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1143123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignass, A.U.; Gasche, C.; Bettenworth, D.; Birgegård, G.; Danese, S.; Gisbert, J.P.; Gomollon, F.; Iqbal, T.; Katsanos, K.; Koutroubakis, I.; et al. European Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Iron Deficiency and Anaemia in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. J. Crohns Colitis 2015, 9, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bager, P.; Befrits, R.; Wikman, O.; Lindgren, S.; Moum, B.; Hjortswang, H.; Dahlerup, J.F. High Burden of Iron Deficiency and Different Types of Anemia in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Outpatients in Scandinavia: A Longitudinal 2-Year Follow-up Study. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 48, 1286–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bager, P.; Befrits, R.; Wikman, O.; Lindgren, S.; Moum, B.; Hjortswang, H.; Dahlerup, J.F. The Prevalence of Anemia and Iron Deficiency in IBD Outpatients in Scandinavia. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 46, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burisch, J.; Vegh, Z.; Katsanos, K.H.; Christodoulou, D.K.; Lazar, D.; Goldis, A.; O’Morain, C.; Fernandez, A.; Pereira, S.; Myers, S.; et al. Occurrence of Anaemia in the First Year of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in a European Population-Based Inception Cohort—An ECCO-EpiCom Study. J. Crohns Colitis 2017, 11, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Khoury, A.; Singh, K.; Kurti, Z.; Gonczi, L.; Golovics, P.; Kohen, R.; Afif, W.; Wild, G.; Bitton, A.; Bessissow, T.; et al. The Burden of Anemia Remains Significant over Time in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases at a Tertiary Referral Center. J. Gastrointestin. Liver Dis. 2020, 29, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, B.R.M.D.; Santos, C.H.M.D.; Santos, V.R.M.D.; Torrez, C.Y.G.; Palomares-junior, D. Predictive factors for loss of response to anti-tnf in crohn’s disease. ABCD Arq. Bras. Cir. Dig. 2020, 33, e1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; He, L.; Zhang, J.; Ouyang, C.; Wu, X.; Lu, F.; Liu, X. Clinical, Laboratory, Endoscopical and Histological Characteristics Predict Severe Ulcerative Colitis. Hepato-Gastroenterology 2013, 60, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alves, R.A.; Miszputen, S.J.; Figueiredo, M.S. Anemia in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Prevalence, Differential Diagnosis and Association with Clinical and Laboratory Variables. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2014, 132, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegh, Z.; Kurti, Z.; Gonczi, L.; Golovics, P.A.; Lovasz, B.D.; Szita, I.; Balogh, M.; Pandur, T.; Vavricka, S.R.; Rogler, G.; et al. Association of Extraintestinal Manifestations and Anaemia with Disease Outcomes in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 51, 848–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutroubakis, I.E.; Ramos–Rivers, C.; Regueiro, M.; Koutroumpakis, E.; Click, B.; Schoen, R.E.; Hashash, J.G.; Schwartz, M.; Swoger, J.; Baidoo, L.; et al. Persistent or Recurrent Anemia Is Associated With Severe and Disabling Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 13, 1760–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, J.; Hartmann, F.; Dignass, A.U. Diagnosis and Management of Iron Deficiency Anemia in Patients with IBD. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 7, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, R.S.; Feitosa, M.R.; Ferreira, S.C.; Rocha, J.J.R.D.; Troncon, L.E.; Troncon, L.E.D.A.; Féres, O. Anemia and iron deficiency in inflammatory bowel disease patients in a referral center in Brazil: Prevalence and risk factors. Arq. Gastroenterol. 2020, 57, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasche, C. Iron, Anaemia, and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gut 2004, 53, 1190–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González Alayón, C.; Pedrajas Crespo, C.; Marín Pedrosa, S.; Benítez, J.M.; Iglesias Flores, E.; Salgueiro Rodríguez, I.; Medina Medina, R.; García-Sánchez, V. Prevalencia de Déficit de Hierro Sin Anemia En La Enfermedad Inflamatoria Intestinal y Su Impacto En La Calidad de Vida. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 41, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergamaschi, G.; Castiglione, F.; D’Incà, R.; Astegiano, M.; Fries, W.; Milla, M.; Ciacci, C.; Rizzello, F.; Saibeni, S.; Ciccocioppo, R.; et al. Prevalence, Pathogenesis and Management of Anemia in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An IG-IBD Multicenter, Prospective, and Observational Study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2023, 29, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Bouguen, G.; Laharie, D.; Pellet, G.; Savoye, G.; Gilletta, C.; Michiels, C.; Buisson, A.; Fumery, M.; Trochu, J.N.; et al. Iron Deficiency in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Prospective Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2022, 67, 5637–5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliadou, E.; Kini, G.; Huang, J.; Champion, A.; Inns, S.J. Intravenous Iron Replacement Improves Quality of Life in Hypoferritinemic Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients with and without Anemia. Dig. Dis. 2017, 35, 444–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Silva, A.D.; Tsironi, E.; Feakins, R.M.; Rampton, D.S. Efficacy and Tolerability of Oral Iron Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Prospective, Comparative Trial. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 22, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, B.; Koningsberger, J.C.; Van Berge Henegouwen, G.P.; Van Asbeck, B.S.; Marx, J.J.M. Iron and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 15, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erichsen, K.; Ulvik, R.J.; Nysaeter, G.; Johansen, J.; Ostborg, J.; Berstad, A.; Berge, R.K.; Hausken, T. Oral Ferrous Fumarate or Intravenous Iron Sucrose for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 40, 1058–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.; Kaneshiro, M.; Kaunitz, J.D. Evaluation and Treatment of Iron Deficiency Anemia: A Gastroenterological Perspective. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2010, 55, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonovas, S.; Fiorino, G.; Allocca, M.; Lytras, T.; Tsantes, A.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Danese, S. Intravenous Versus Oral Iron for the Treatment of Anemia in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Medicine 2016, 95, e2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, R.A.; Gaskell, H.; Rose, P.; Allan, J. Meta-Analysis of Efficacy and Safety of Intravenous Ferric Carboxymaltose (Ferinject) from Clinical Trial Reports and Published Trial Data. BMC Blood Disord. 2011, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffbrand, A.V.; Stewart, J.S.; Booth, C.C.; Mollin, D.L. Folate Deficiency in Crohn’s Disease: Incidence, Pathogenesis, and Treatment. BMJ 1968, 2, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, C.; Ross, V.; Mahadevan, U. Micronutrient Deficiencies in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: From A to Zinc. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2012, 18, 1961–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Guo, H.; Jabir, M.S.; Liu, X.; Cui, W.; Li, D. Associations between Folate and Vitamin B12 Levels and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2017, 9, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]